In mid-March as the coronavirus swept through the U.S., Rafael Gonzales Jr. watched the news, and all he could do was call the virus by a Spanish swear word: cabrona, the bitch. Like so many other people in the United States, he and his wife began working from home full-time, and Gonzales was surrounded by news of the virus’s devastation. But the worldwide crisis also sparked his creativity, giving birth to an idea that has brought joy to many as the pandemic wears on.

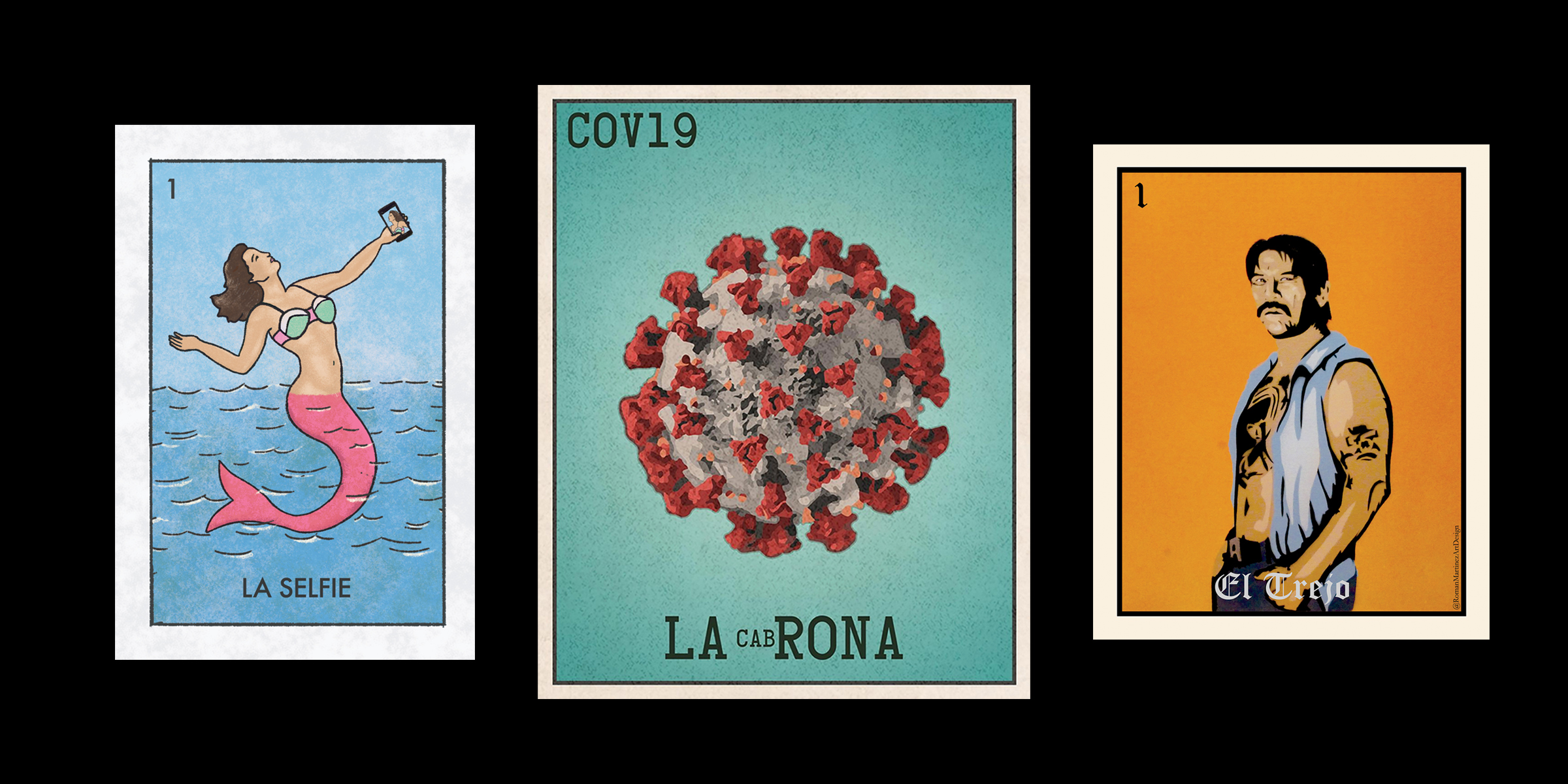

“I had a small idea of basically getting out the frustration of having to deal with COVID-19,” he tells TIME. That small idea was a joke, a play on words comparing cabrona and corona. He went on to illustrate the joke in a format recognizable to millions of Latinos around the world: Lotería.

Though by day Gonzales works as a lab manager and compliance officer at the Feik School of Pharmacy at the University of the Incarnate World in San Antonio, he enjoys doing graphic design on the side. So he created “La cabRONA,” an illustration of the virus designed in the style of the classic Don Clemente Jacques’ Lotería, a Mexican game of bingo made up of 54 images that have become entrenched in Latino identity.

Though Lotería is a board game, its roots go deeper than Monopoly or Scrabble. The game is a cultural tradition for many Latinos, and artists like Gonzales and Mike Alfaro, creator of Millennial Lotería, are giving it a new life.

Their versions of the game are played the same way Clemente’s Lotería is played. Friends, family or even complete strangers pick a tabla (board) containing 16 images printed out on a 4×4 grid. An announcer holds on to a deck of cards, each containing one of 54 images. One at a time, the announcer will draw from the deck and name the image, or make it more challenging by saying a riddle or developing a story line. If the player sees the image drawn from the deck on their tabla, they can mark it, traditionally with a dry pinto bean or a stone. The first player to get four in a row wins Lotería.

The game is popular with families, particularly around holiday celebrations in part because people of all ages can play. It’s also played in public spaces like ferias (fairs), where friends and strangers gather and place a bet.

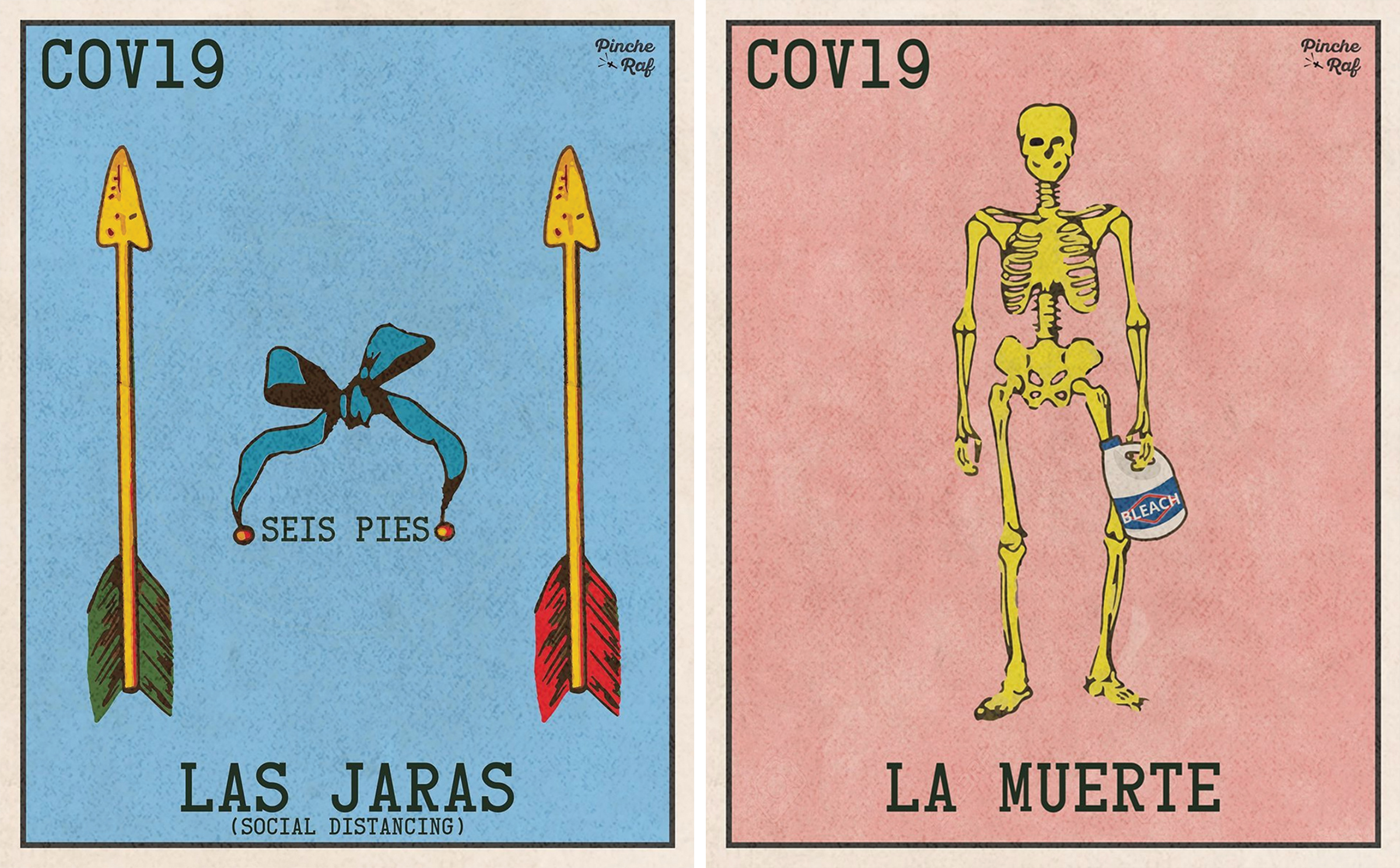

After publishing the “La cabRONA” illustration on Instagram on March 24, Gonzales decided to continue with the COVID-19 theme and design more Lotería cards. His clever, sometimes critical, images were met with hundreds of “likes” and comments. By mid-April, Gonzales produced 31 images that he and his wife turned into “Pandemic Lotería” on their kitchen table. Gonzales says that within 24 hours of taking pre-orders for the game, the couple sold more than 800 copies online. To keep up with sales demands, Gonzales and his wife began a partnership with a local retailer, Felíz Modern.

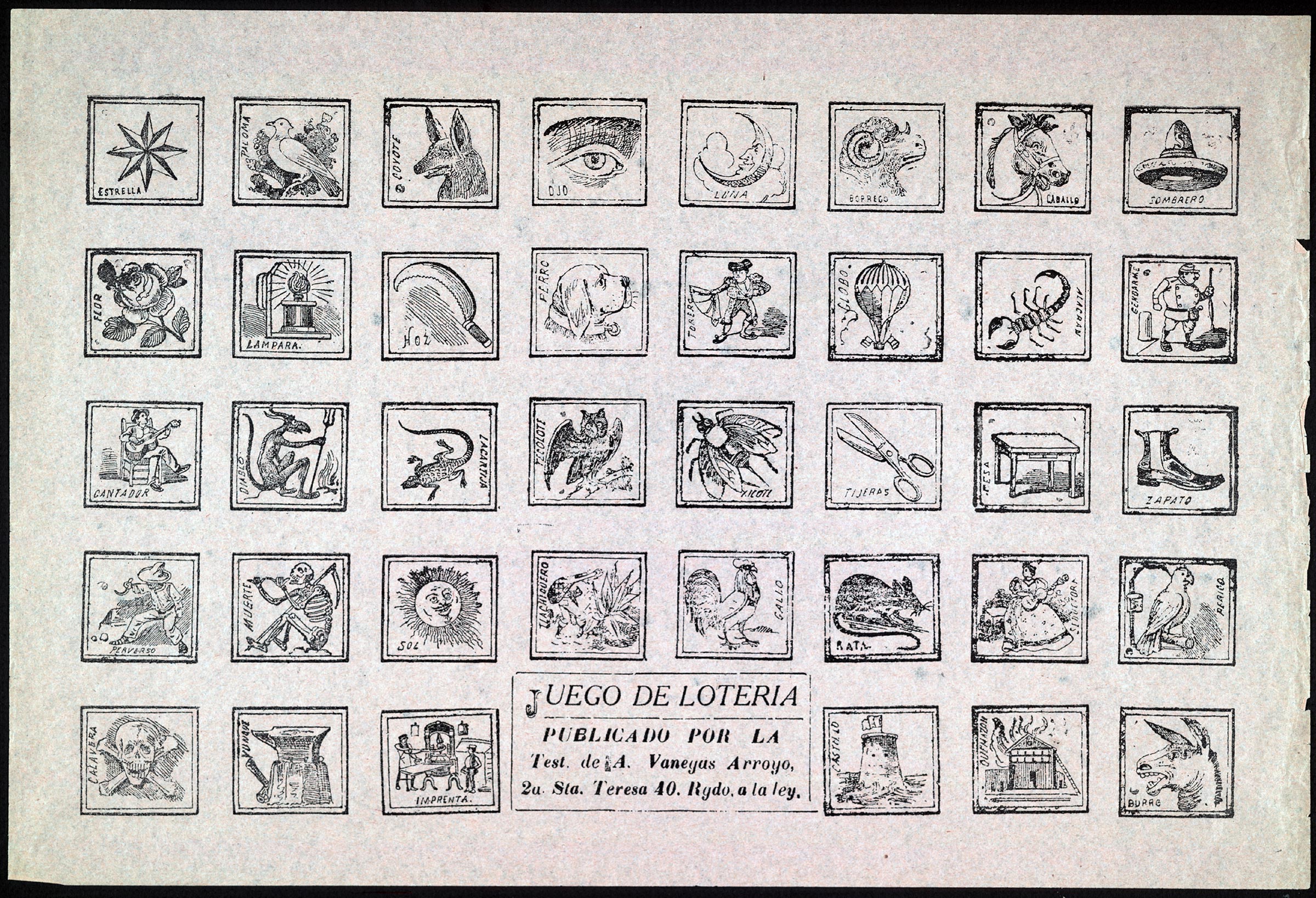

Gonzales is now among a range of artists throughout the U.S. and Latin America who have redesigned the classic Lotería, which is now more than a century old, though none have come as close to popular as the Clemente version. The most famous Lotería design we know today was created by Clemente, a French immigrant in Mexico who printed what he named the “Don Clemente Gallo” Lotería in his own factory. The version that we know today can be traced back to the early 1920s, according to Gloria Arjona, a Spanish lecturer at the California Institute of Technology who has done extensive research into the origins of each of Clemente’s designs, and recently published a book titled ¡Lotería!.

“I am sure that the Lotería is not only a game, it’s a tradition,” Arjona tells TIME. “It’s part of our identity.”

Arjona herself has participated in reimagining the classic Clemente Lotería game. Earlier this year, she coordinated a team to create live artistic renditions of popular Lotería cards. Alejandra Hernandez Talapa was one of the actors who partnered with Arjona to create a live version of “La Chalupa,” a woman with Indigenous roots who sells produce from her canoe.

“When I was a child, it was just a matter of winning the game,” Hernandez Talapa tells TIME, adding that portraying La Chalupa allowed her to reconnect with her roots and understand the origins of her character. “Now I know the history of this…there’s that consciousness of where this game came from, what was the purpose, because it has a cultural history.”

It’s impossible to know how many people have recreated Lotería because, by nature of the game, anyone can make one with their own unique designs at home. Today it is most common to purchase a Lotería game online or at ferias, flea markets or Latino stores, but before Clemente’s version came along, most people made a Lotería at home. Clemente’s version of Lotería that has become the most widely recognized today is also itself a recreation of Loterías that can be traced back to Italy in the 15th century. Before the game was commercialized in the early 20th century by Clemente, families, friends and neighbors painted their own unique versions.

More recently, artists have made Millennial Lotería, Women Power Lotería, Estar Guars Lotería and Lotería Salvadoreña, to name a few. In October, presidential candidate Joe Biden aired a campaign ad narrated by Julian Castro featuring new Lotería designs about American jobs. Texas fast food chain Whataburger even offers a free themed Lotería pack. These versions are all available online.

Clemente’s images like “La Sirena” (the mermaid), “La Rosa” (the rose) or “El Gallo” (the rooster) are so iconic, they are featured often on murals, tattoos, T-shirts, candles, matchbooks, vases—any surface area you can think of—throughout Mexico, Central America and many parts of the U.S.

“Lotería is so important to people and it’s such a fun art form and so visual that it only makes sense that people would try to make their own cards and give it their own spin,” Alfaro tells TIME. “I’m all for all these different Loterías coming out. There’s space for everybody to make this art form their own.”

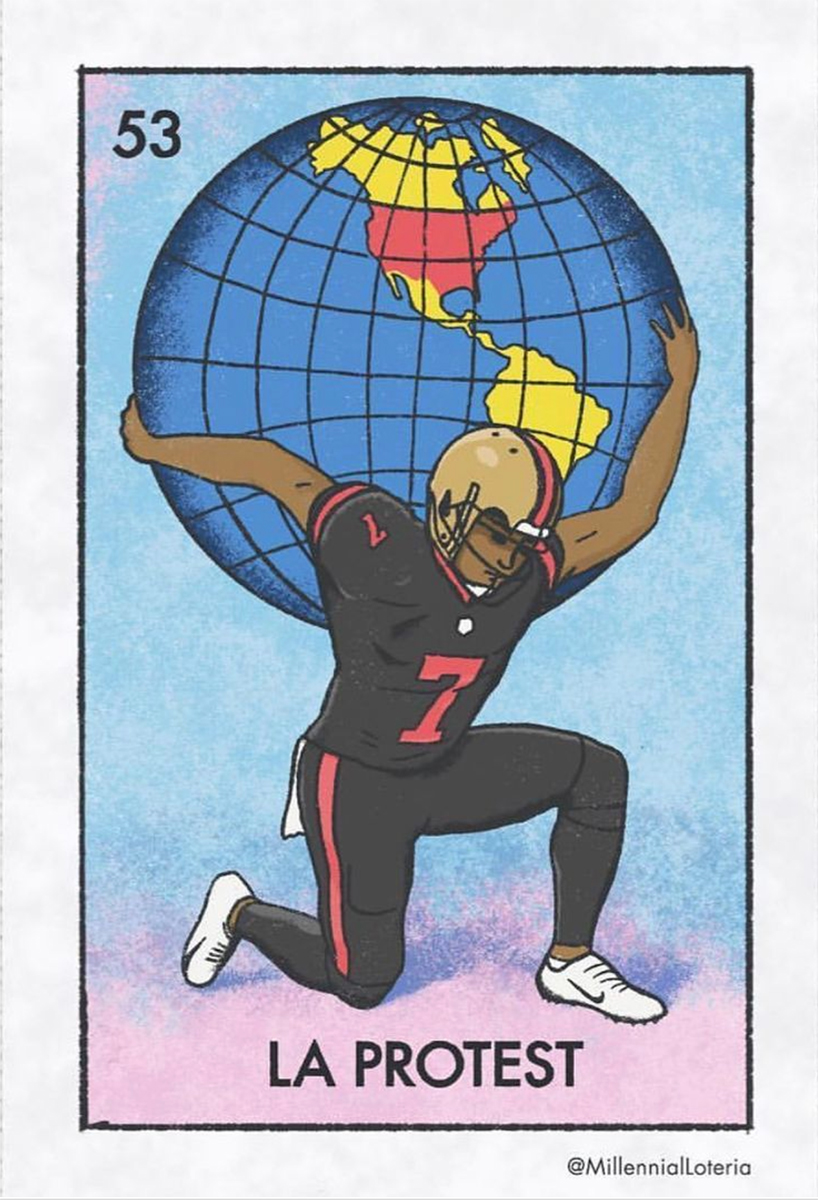

Alfaro created Millennial Lotería first as an instagram account in 2017. It has since become a bestseller on Amazon, was featured in the Starz television series Vida, has sold over 70,000 copies, and resulted a publishing deal with Blue Star Press and Penguin Books who now distribute the game.

Alfaro is now based in Los Angeles, but is originally from Guatemala. He says the idea for Millennial Lotería came to him when he visited his home town and pulled out his old version of Clemente’s Lotería. With it came feelings of nostalgia, and happy memories of playing with his family. But he also realized the game’s depictions of people are problematic and stereotypical.

“It just felt like it needed to be modernized and updated,” Alfaro says. “I didn’t want people to cancel Lotería…I wanted to keep it alive, and keep the tradition going. Make it more modern and something that people feel excited to share and play with other people from different cultures.”

Alfaro’s redesigns include Clemente’s “La Bandera” (the flag) as “El Pride,” now a rainbow flag. Clemente’s “La Dama” (the lady) was redone as “La Feminist.” He has also designed several new cards that provide commentary on 2020. Clemente’s “El Mundo” (the world), for example, which depicts a man carrying the world on his shoulders, was redesigned by Alfaro in several different ways. One, as a student in debt carrying the globe, but then he changed it again to a Black football player carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders and named the card “El Protest.”

While Alfaro’s and Gonzales’s Loterías can be considered a snapshot of the world today, Arojana says the Clemente Lotería is also a reflection of its era, including prejudices. The game features nine people, all stereotypical depictions of indigenous people, upper class white people and Afro Latinos.

“It is a reflection of, I would say, colonial times,” Arjona says. “These images display our prejudices, display the stereotypes.”

In Lotería, however, Alfaro says he saw an opportunity to design a game that is inclusive of all aspects of Latino identity.

“It’s easy to look back in history and see things that are problematic,” Alfaro says, adding that millennials and Gen Z’ers are particularly good at that. “I think the great thing about Millennial Lotería is that we have so many cards that each card can represent one little aspect of what it means to be Latino and what it means to be a millennial Latino. So you can have all these different parts because Latinidad is so different.”

Gonzales says his goal with “La cabRONA” was to “bring a quick little laugh” to people dealing with the stress of COVID-19, and to let out his own frustrations. As the pandemic continued, there also arose opportunities to share criticism of public officials for their handling of the virus.

Some of his criticism is subtle, for example replacing Clemente’s scythe in “La Muerte” (death) with a gallon of bleach. But others are more direct. One illustration, published in April, shows a campaign yard sign for Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick tossed in a garbage bin. The illustration is not a part of the official Pandemic Lotería game, but Gonzales shared it anyways as a way to vent frustration with Patrick’s push to reopen businesses despite the pandemic.

“I’m a scientist,” Gonzales says. “To me, truth telling is important, and I think that has been a problem with this administration…I think my motivation is that it’s about truth telling, saying what this pandemic really is, and what we can do to curve its impact on us.”

In El Paso, Texas, the success of one of Roman Martinez’s Lotería designs led to collaboration on another. He started by publishing redesigns with a Star Wars theme, and named it Estar Guars Lotería. His game got the attention of a few film producers, including the son of Mexican movie star Danny Trejo, an active member of El Cine, a nonprofit in Los Angeles dedicated to promoting Latino culture through film.

Now Martinez designs Lotería cards to commemorate and promote iconic Mexican actors, singers, directors or cinematic characters in collaboration with El Cine—everyone from Selena Quintanilla, to Tin-Tan, whose real name is Germán Valdés, an actor, singer and comedian famous as an iconic pachuco, an early 1900s counterculture of Latinos who dressed in zoot suits and listened to jazz music.

“Lotería, I wanna say it’s universal,” Martinez says. “It’s just been ingrained in our culture, and it’s been adapted so many times…It just seemed like a logical extension with what we’re doing, particularly El Cine with these beloved characters.”

El Cine Lotería now has 54 designs, and Martinez plans to publish an updated version in February in a new style, and featuring new depictions of John Leguizamo and other new faces.

“I can’t be more thrilled,” Martinez says about the success of both his Lotería games. “It’s nice to be able to create something that people want and be able to provide for your family.”

“[Lotería] is cultural,” Martinez adds. “It’s such a personal game because people grow up with it, they play it in schools, as you get older you play it with your family at the holidays.”

So when it came down to making El Cine Lotería, Martinez thought back to his childhood listening to Pedro Infante with his grandparents. “I gotta have this guy,” he said, and added Infante to his list of icons to include in the game. At the end of the day, it was a chance for representation.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Jasmine Aguilera at jasmine.aguilera@time.com