Around the world there are different versions of the jolly, bearded man who gives gifts to children in December or, in some countries, January. Unlike the bloated, red-coated father Christmas of the West, Russia’s Santa Claus, known as Ded Moroz (Grandfather Frost), is slender with a wizard-like flowing beard and he wears a long robe that comes in different colors, such as blue and white.

He is assisted not by elves, but by his beautiful granddaughter Snegurochka (Snow Maiden). His sleigh is powered not by reindeers, but three steely horses. What really sets Russia’s Santa Claus apart from his Western counterpart is the turbulent century that he’s faced. He has survived a violent social and political revolution that saw him go from beloved to banned as a subversive element, then beloved again and hailed as a symbol of the true Russian spirit.

The trouble for Ded Moroz and his granddaughter sidekick, who originate from pagan Slavic mythology, began with the creation of the Soviet Union in 1922. Under the new communist regime, which was built on the promise of creating social equality, religion was banned as it was deemed a bourgeois instrument to repress the working class. Many clergy and some believers of the Russian Orthodox Church were sent to labor camps or killed. In 1928, Ded Moroz was banished into exile having been “unmasked as an ally of the priest and the kulak [supposedly rich peasants who the communist party considered a threat to their power],” Karen Petrone explains in her book, Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades. Christmas day, celebrated on Jan. 7 in Russia and some Eastern European countries that follow the Julian calendar, was erased and all festive celebrations were forbidden. Anyone who broke the rules risked arrest.

In a sharp turn in 1935, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin decided to bring in Ded Moroz from the cold as part of efforts to “boost his popularity and assert stability,” says Petrone, a history professor at Kentucky University. An aggressive period of collectivization between 1929 and 1932, when the government forced farmers to give up their individual lands and join collective farms, sparked violent opposition. Millions of peasants who resisted the policy were sent to prison camps. The disruption caused by collectivization led to a famine that killed at least five million people across the Soviet Union.

Stalin lifted a ban on celebrations but only on New Year’s eve to avoid giving the festivities a religious significance and instructed Ded Moroz to deliver presents on the morning of Jan. 1. He also brought back the tradition of putting up Chirstmas trees in homes, previously deemed an “economic evil” says Petrone, and rebranded them New Year’s trees. “Life has become better, comrades, life has become more joyous,” Stalin said in 1935 as he promised workers better living standards.

State-controlled footage of New Year’s eve celebrations showing happy workers dancing and drinking to the health of Stalin painted the picture of a more prosperous era. But in reality, life did not improve for the majority of the population. Such footage was part of the state propaganda machine that tried to present the Soviet Union as a “superior system” to the capitalist West that was in the grip of economic depression, says Petrone.

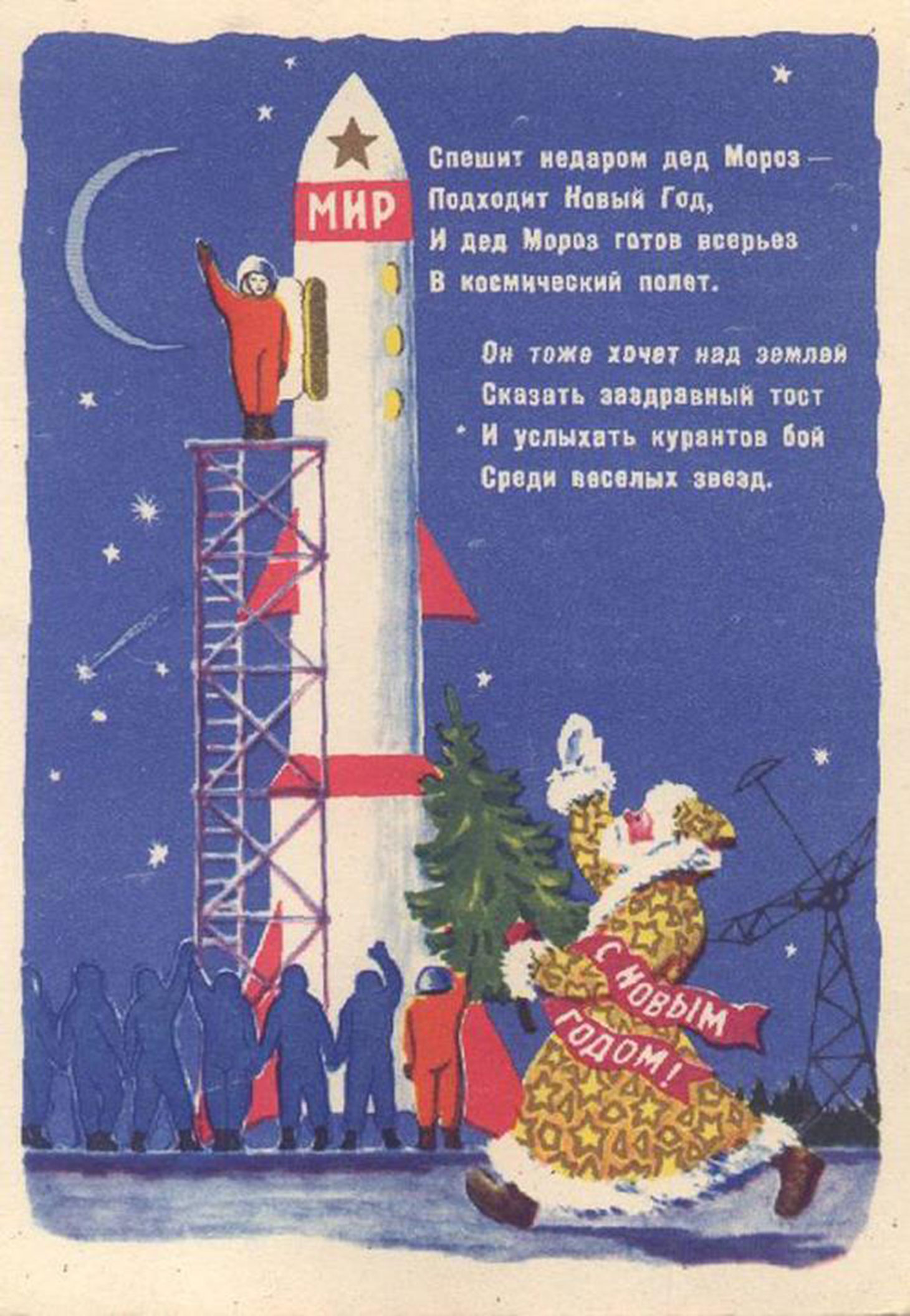

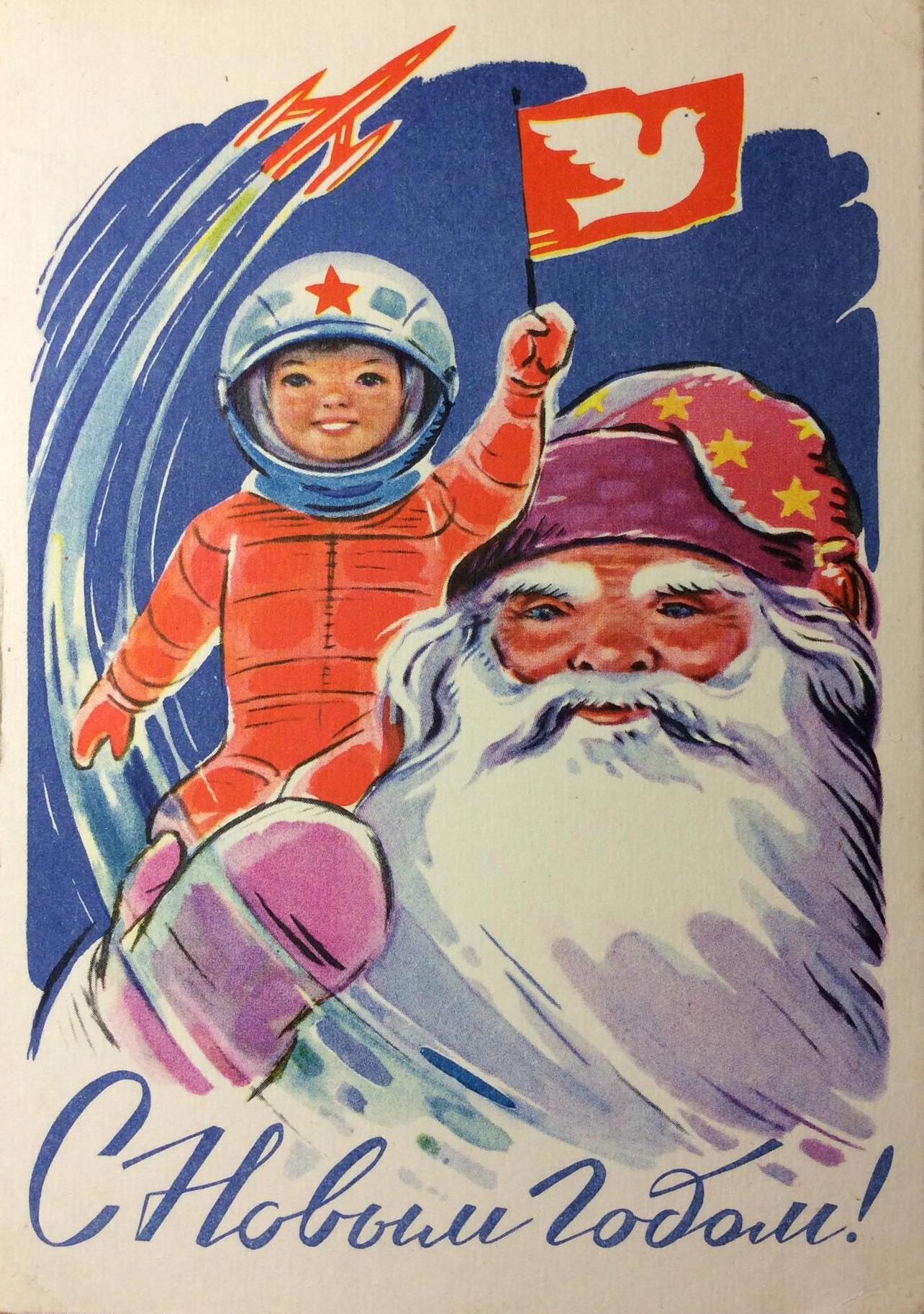

More than just the giver of gifts, Ded Moroz was the giver of pro communist PR. In 1949, the Associated Press reported wrote that at gatherings with children, Ded Moroz ‘customarily ends his talk with the question “to whom do we owe all the good things in socialist society?” to which it is said the children chorus reply “Stalin.”’ In the 1960s, at the height of the space race between the Soviet Union and U.S., Ded Moroz appeared in flying rockets on cards and posters, some with the caption: “Ded Moroz is seriously ready for the space flight.”

Meanwhile, some U.S. officials used Ded Moroz to highlight the supposed dangers of ending religious practices. In 1966, Senator Joseph McCarthy warned that “brutal cynicism” was on the march in the U.S., reacting to a 1962 ban on government sponsored prayer in public schools, “rivaled only by the Soviet Union where they eliminated Santa Claus and brought in Grandfather Frost. Will that satisfy the children of America?”

As communism began to fall across Europe in 1989, Ded Moroz fell out of favor in some satellite states in eastern Europe, where the Russian gift-giver had been exported. Countries such as Bulgaria and Romania restored their original versions of Santa Claus as they returned to their old customs.

When Western cultural influence began to seep into the new capitalist Russia in the 1990s and with it, Coca Cola billboards featuring a beaming Western Santa and ornaments of the tubby man in store fronts, Ded Moroz decided to get into business. In 1998, then Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov and local authorities marketed Veliky Ustyug, a small town surrounded by pine forest in the northern region of Vologda, as the home of Ded Moroz and built him a 12-room wooden palace. Open all year round, the palace draws in about 250,000 guests annually. Guests can rent cottages near his residence, where they have access to a swimming pool, sports facilities such as skis and sledges, a restaurant and a New Year’s souvenirs store. In the capital Moscow, Ded Moroz has branches in Kuzminki Park, and on the 55th floor of the Imperia Tower in the city center for visitors over the New Year. Ded Moroz and Snegurochka regularly feature in adverts, including for Pepsi and Russia’s Sberbank.

Ded Moroz is still the most popular gift-giver in today’s Russia and the New Year is the main winter holiday. But there seems to be a rivalry between the Slavic wizard, who some politicians promote as a true symbol of Russia’s spirit, and his Western peer who is often viewed as an “imposter”.

In 2008, then-Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, who had been taking steps to revive Soviet nostalgia and drawing closer ties with the Russian Orthodox Church visited Ded Moroz’s wooden palace. The same year, Luzhkov said: “Take a look at our huge, handsome Ded Moroz. The puny Santa Claus is a far cry from him!” after escorting Ded Moroz through central Moscow. Boris Gryzlov, a parliament speaker at the time, declared: “No one will ever be able to take away Ded Moroz from Russia—not Santa Claus nor any other imposters.”

Some Russians feel very passionately about their traditional winter figure and their desire to protect him from Western culture. In December, Denis Amosov, a marketing specialist from the Siberian city Tomsk, launched a lawsuit seeking 30 million rubles ($411,000) in compensation for “moral damages” against Coca Cola for “imposing” the Western Santa Claus in its Russian advert. He has also appealed to Putin and the Ministry of Culture to limit “Santa propaganda” in the country. In an Instagram post, Amosov said: “There is an association among adults and children that a Happy New Year is only possible with Coca Cola and Santa Claus, Russian traditions and centuries-old history are being lost”.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com