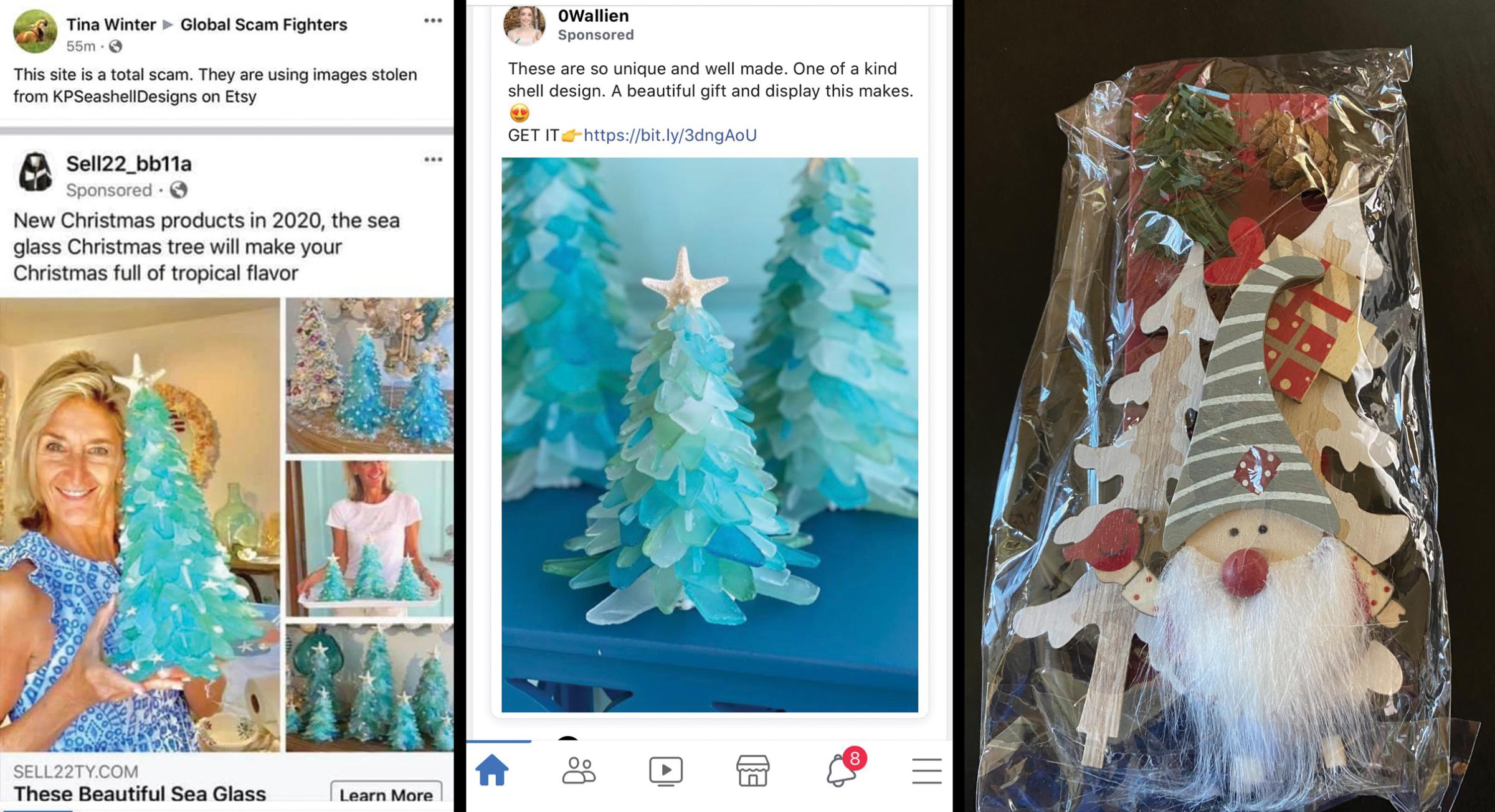

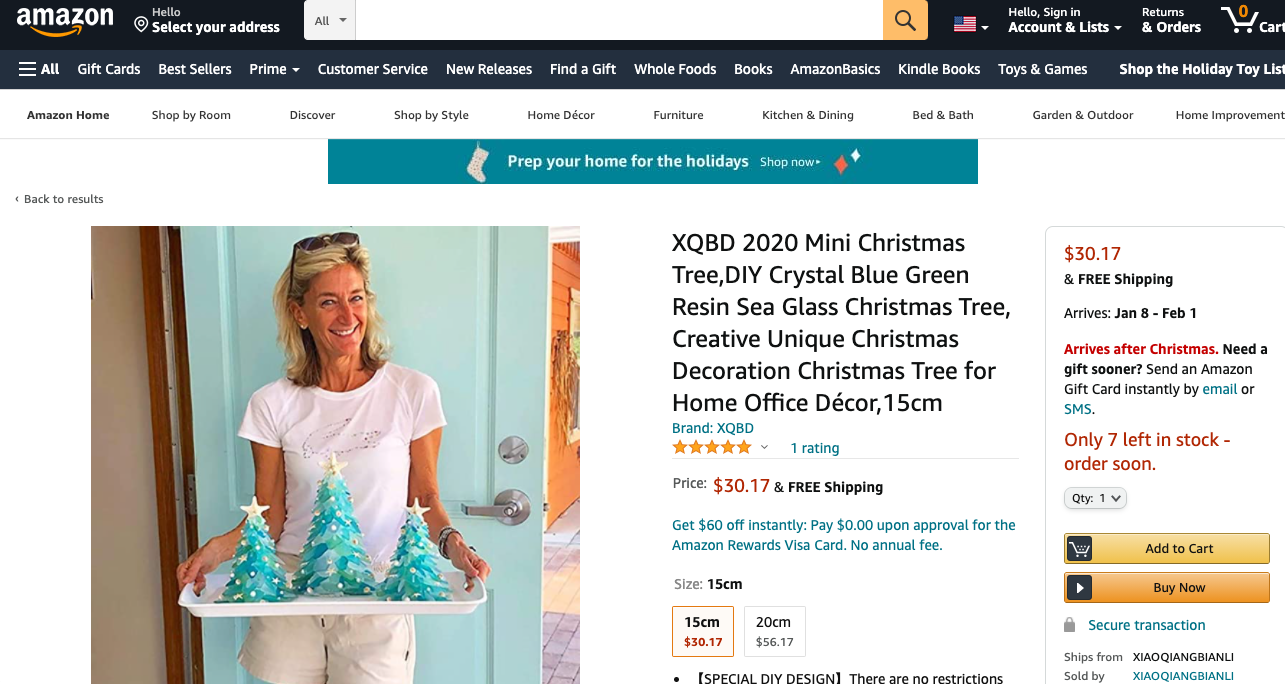

The sea glass Christmas trees appeared on Richard Edmonson’s Facebook feed in October, in between a relative’s photo and a friend’s meme. Their boughs were varying shades of translucent blue and turquoise; a starfish sat on top. Edmonson, who lives in Edinburg, Tex., didn’t click on the post, but it reappeared the next day, and then the day after that. “The more I saw it, the more it looked legit. I thought it would be a perfect Christmas gift for my sister,” he says. He ordered two for $40.

The trees crept onto Heather Hopper’s feed around the same time. Hopper, who collects sea glass in Oceanside, California, was impressed by their craftsmanship and also clicked through after seeing the post several times. Further reassured by photos that showed the trees with their creator Kristi Pimentel in her Florida home studio, Hopper ordered three.

But there was one problem: Pimentel wasn’t involved at all. Someone was swiping photos from her Etsy and putting them on websites and social media ad campaigns. People would see those pictures and order her trees, and then only receive dollar store flotsam. Edmonson says he got dinky plastic cones, while Hopper says she received a wooden gnome that was “the ugliest thing I’ve ever seen.” Pimentel, meanwhile, was deluged with dozens of confused or angry customers every day demanding their money back, despite the fact she hadn’t processed any of their orders.

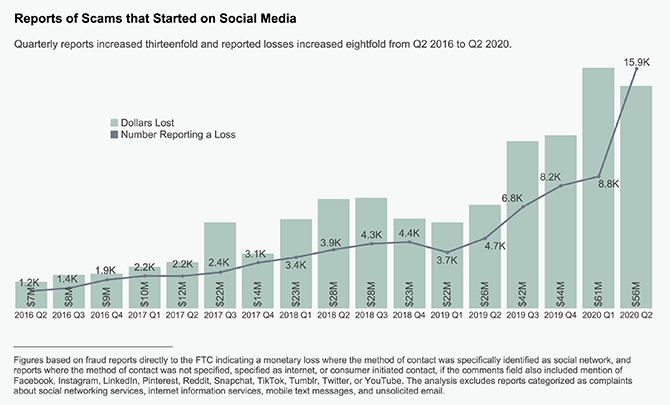

These stories aren’t isolated incidents. An almost-identical scene is unfolding over and over in homes across the country and world. Facebook or Instagram users see an ad on their feed for a discounted product. They purchase the item through PayPal, and then a knick-knack of no value arrives. The vendor disappears or tells them to return the package back to China—a step which often costs more than the original order—while PayPal often sits on the sidelines. In October, the Federal Trade Commission reported that the number of complaints about scams that started on social media has more than tripled in the past year, with reported losses adding up to $117 million in just the first six months of 2020.

And these scams are not the work of individual small-time crooks. Many of them appear to be part of systematic, well-oiled global operations, designed to take advantage of the lack of oversight on social media marketplaces and the influx of novice online shoppers brought by pandemic quarantines, and the shutdown of brick-and-mortar stores. And the spoils of one of the largest known shopping scam networks may be benefiting a major Chinese company: the publicly traded TIZA Information Industry Corporation INC., whose 2019 revenue was $549 million.

The global nature of these scams, combined with the relatively low value of each individual con, means that they have largely escaped the scrutiny of law enforcement. Meanwhile, the volume of shady fraudulent activity is accelerating over the holiday season, as people search for affordable gifts for their loved ones. Experts worry that if unchecked, American wallets will be bled to death by a thousand cuts—and a digital ecosystem that serves as crucial infrastructure for small businesses could crumble under a torrent of spam and a general lack of trust. “We’re all suffering from that sucking sound of hundreds of billions of dollars leaving our economy,” Kristin Judge, the CEO and president of the Cybercrime Support Network, says. “The money that would have been spent on Main Street—it’s now China or somewhere else.”

The Rise of Shopping Scams

Scamming has long been a fundamental element of the internet. According to Gallup, one in four Americans is a victim of cybercrime each year, from relationship scams to fake IT support to Ponzi schemes to phishing. Last year, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center received 467,361 complaints, with reported losses exceeding $3.5 billion.

And the problem has only festered since the start of the coronavirus, when millions of people across the world retreated under social distancing rules and turned to the internet for almost all communication. Many of these users are online novices who have become easy victims for new and old ploys alike. In March and April, fake COVID remedies, medicines and sanitizers began flooding the internet. 3M, one of the largest global makers of N95 masks, investigated 4,000 reports of fraud, counterfeiting and price gouging as consumers scrambled to protect themselves and their loved ones. In the middle of the year, a swelling wave of cryptocurrency scams invoked the coronavirus to extort or blackmail people.

While there are countless different types of rackets that each deserve their own investigations, the e-commerce scam is perhaps the fastest-rising and most worrisome. In 2015, just 13 percent of scams reported to the Better Business Bureau Scam Tracker were online purchase cons; this year, they make up 64%. Online shopping scams are also the number one fraud in every age group, according to the Federal Trade Commission.

How do these scams work, who do they affect, and what are the involved major corporations doing to stop them? Here’s a step-by-step examination.

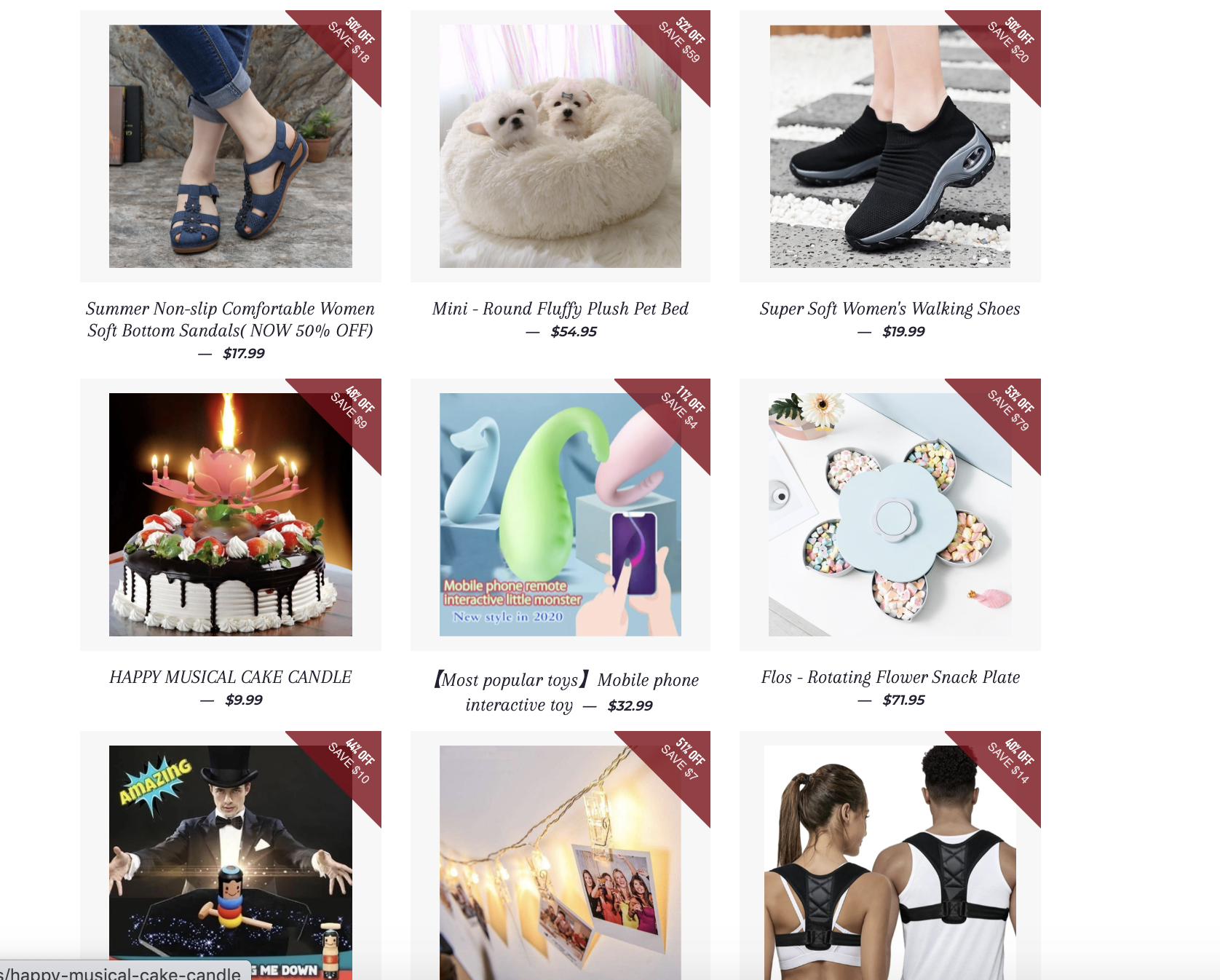

Scammers Create Fake Shopping Websites

Let’s revisit the story of Heather Hopper in California, who, after clicking on a Facebook link, was sent to a website called Apriloina.com. If you go there yourself, nothing looks particularly amiss. “Culture Chic” is written across the top in a stylish serif. A tidy grid shows a series of discounted products, from bracelets to vegetable slicers. There’s a terms of service and privacy policy, and the symbols of PayPal and MasterCard emblazoned at the bottom.

But a major clue about Apriloina’s inauthenticity can found on the “About Us” page, where a familiar sentence appears: “We love every passion and interest on Earth because it is a reference to your UNIQUENESS.” If you search the same garbled phrase as above on Google, you’ll get 65,000 results. Click on virtually any of those, and you’ll land on another store which looks eerily similar in layout and language. Upon further investigation, more shared attributes will start to emerge: the same IP addresses, customer support emails, phone numbers, and warehouse shipping addresses in Mainland China. Their photos overlap; and many will have either very bad reviews or very good reviews filled with repeat phrases and malapropisms. (“It is seen that it is sewn factory,” read two identical reviews for a men’s hoodie on ByDivStore.com.)

Scam sleuthers believe that these connections are no coincidence—and that there are thousands of sites being created by just a handful of powerful, centralized organizations. They have dubbed that particular organization the “UNIQUENESS NETWORK”; another one with at least hundreds of websites is called “Kokoerp.” Sleuthers believe these networks buy domain names en masse, all with vaguely English but largely nonsensical names—GoShoesNC, KidsManShop, BoldWon—so that when one becomes compromised, it will get shut down and replaced by another. Their interchangeability makes it extremely hard for authorities to take action. “You report maybe a dozen and the next day, three dozen more show up,” Suzie Hebert, who investigates scam networks in conjunction with the ECommerce Foundation initiative ScamAdviser.com, says. “I feel like we’re turning in circles.”

Many of the sites make use of the online shopping platform Shopify. Jorij Abraham, the general manager of the ECommerce Foundation, says that because Shopify allows you to set up a shop for 14 days with no credit card required, scammers will simply set up shops, shut them down after two weeks, and start another one. “We have an incredible amount of people complaining about Shopify shops not delivering products,” Abraham says. “They’ve done a really terrible job.”

“We take concerns around the goods and services made available by merchants on our platform very seriously,” a Shopify spokesperson wrote in a statement to TIME. “Shopify’s Acceptable Use Policy clearly outlines the activities that are not permitted on our platform, and we don’t hesitate to action stores when found in violation.”

Scammers Swipe Product Images From Real Businesses

As seen on “Apriloina,” scammers cast the widest net possible of any item that someone might be searching for on Google. There’s workout equipment, lawn mowing gear, jewelry and whiskey decanters; bolts and screws and high fashion garments. Puppy scams—in which people think they are buying actual puppies but receive nothing or stuffed animals—skyrocketed over the past year, with bored people at home searching for cute companionship. Other scams take their images from high profile stores like Patagonia and L.L.Bean—but those companies have more resources to fight fraud on a larger scale, and customers are more likely to go straight to their official site.

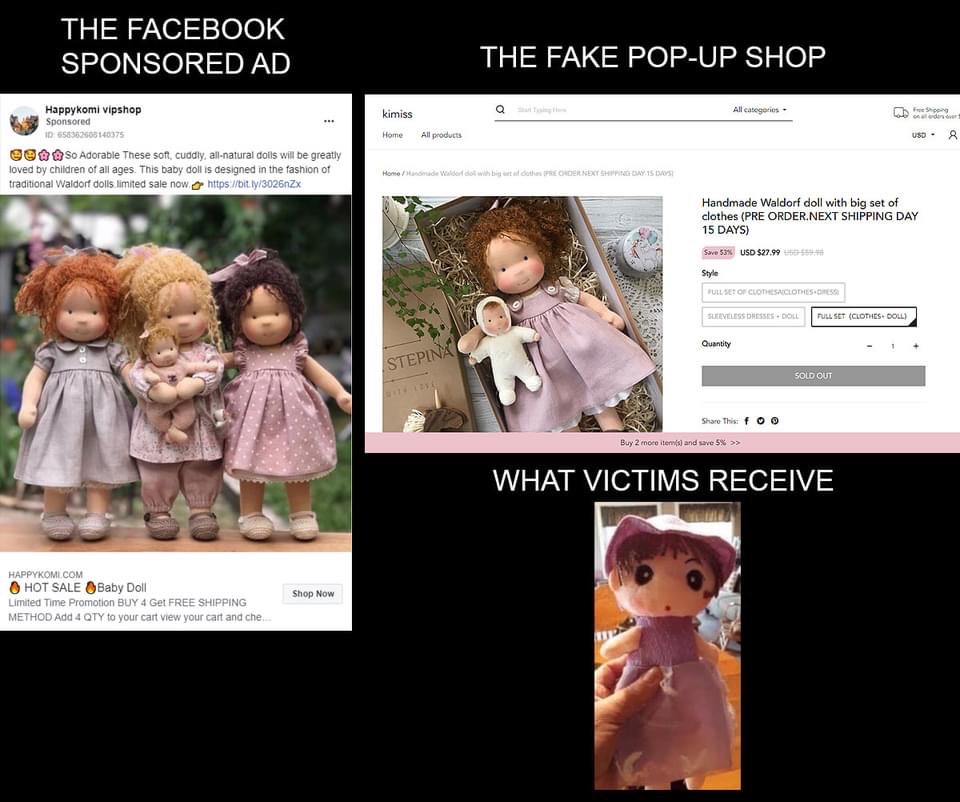

So it seems scammers have more success swiping images from small businesses, often found on Etsy or other e-commerce websites. These unique items stand out to scrollers in a sea of content, and their original websites may be as ramshackle as the scam pages, making it difficult to discern the actual source. As a result, small business owners across the world are turning into these scammers’ collateral.

In the United Kingdom, Ildiko Duretz has been selling handmade dolls for children for the last 16 years. Each one takes her a week to make by hand, and can fetch up to £900 on the market from collectors. This fall, however, ads began appearing on social media selling them for £15 to £60. The scam websites not only stole photos of her dolls, but also her website banner and written descriptions about her dolls and herself. It wasn’t long before Duretz started getting dozens of messages from those who had been duped. “I’m still getting 10 to 20 messages a day,” she says. “They’re leaving negative reviews on my Facebook page saying, ‘Your dolls are rubbish.’ I have to spend two hours a day responding to people, otherwise they think I’m the scammer. It’s an absolute nightmare.”

Duretz is particularly upset that mostly older people email her. “So many people write to me saying, ‘I bought it for my grandchild,’” she says. She says she reported several scam websites to the London Police’s fraud reporting center, but was told that they needed a critical mass of victims to investigate. When she went to a copyright protection firm in London to seek guidance, she was told there was little they could do since the scammers were in China. “I would like for somebody to tell me what to do,” she says. “I have no idea where to go to stop this.”

Scammers also target seasonal or holiday-related products, hoping to catch the eye of parents frantically searching for gifts for their children and other family members. In the lead-up to Halloween, an ad for a singing pumpkin duped many across the country. More recently, Christmas-related products have flooded feeds, including Pimentel’s trees. Abraham, at the ECommerce foundation, says that scams increase by 40% during the holiday season. “Our biggest traffic peak is between Christmas and 7th of January, because that’s when people become aware that they didn’t get their product,” Abraham says. “It gives a lot of people a very bad Christmas.”

Scammers Blast Their Ads On Social Media

Scammers would make a decent amount of money just off waiting for people to find their phony shops through search engines. But that passive approach doesn’t have nearly the same reach as campaigns on social media—and particularly, on Facebook.

Once a place to talk to (or poke) your friends, Facebook has become one of the world’s largest superstores. Last year, the company generated $69.7 billion from advertising, accounting for more than 98% of its total revenue. These ads have become one of the most important tools for businesses to grow and reach customers: there are millions of small businesses on the platform trying to court Facebook’s 2.7 billion monthly active users.

This dynamic has made Facebook the primary feeding grounds for scam artists. In the aforementioned FTC study, 94% of victims said their scam originated on Facebook or Instagram (which Facebook owns). Scammers take the same maximalist approach on Facebook as they do with domain names: they create multiple Facebook pages for single items and then blast out targeted ads—often to older women—using one account at a time. One page on Facebook’s ad library, for example, shows that a now-defunct scam page called Byagadget ran 8 ads for a zip-up top over one week in June. The Byagadget page spent $200-$300 on the ads, which were seen 7,000 to 8,000 times; 39% of people who saw the ads were women over 65.

As ads like that one increasingly dominate feeds, an irate community has grown on Facebook dedicated to reporting these scam ads whenever they appear. But members of these communities, like Facebook Ad Scambusters and Scam Alert Global, say that their complaints are often ignored or overruled, with Facebook representatives deeming the pages as within community standards.

Pimentel says she’s reported fake ads of her trees dozens of times and also filed a formal report with Facebook alleging intellectual property theft. “But a reply came back saying there wasn’t enough evidence, and that they couldn’t take it down because there were other things sold on the site,” she says.

Kathy Waters and Bryan Denny, two anti-scam activists, have experienced the same frustrations since 2016. Denny, a retired U.S. colonel, has been the subject of countless romance scams, in which scammers pretend to be him in order to extract money from lonely women. Waters and Denny say they’ve met with Facebook representatives several times and shown them fake accounts over four years, but that nothing has changed. “There hasn’t been any improvement since we started,” Denny says. “Facebook has as many excuses as to why this problem isn’t fixed as the scammers have in saying why they can’t Facetime with you.”

An article by Buzzfeed News published in December reported that Facebook ad workers were told to ignore suspicious behavior unless it “would result in financial losses for Facebook.” A separate Buzzfeed article reported that Facebook earned more than $50 million in revenue from a single dishonest San Diego marketing agency.

A Facebook spokesperson denied that the company profits from scam ads: “We have every incentive—financial and otherwise—to prevent abuse and make the ads experience on Facebook a positive one,” they wrote. Facebook also says it is more active than ever in removing bad content, removing 112 million organic posts in the first nine months of 2020, up more than 35% from the same period in 2019. Last month, the company launched an awareness campaign in conjunction with the Better Business Bureau about the increase of shopping scams during the holiday season.

The Facebook spokesperson also responded directly to a question about Pimentel’s situation, writing: “We’ve deleted multiple pages associated with these ads for violating our impersonation policy. We have policies in place to help protect people and businesses from scammers looking to take advantage of them, but our enforcement isn’t perfect. We take the violations that have affected Ms. Pimentel seriously, and we are actively investigating other pages and accounts associated with these ads.”

The Money Flows From Paypal Accounts to China

Facebook is somewhat shielded from blame because the actual transactions largely don’t happen there: the buyers are routed to the aforementioned scam websites, which often use PayPal. Many consumers interviewed for the story said the presence of PayPal served as the most important reassurance that it wasn’t a scam. “When I saw PayPal, I thought, ‘This must be legit. I can trust them,’” says Richard Edmonson, the Edinburg, Texas man who thought he was purchasing sea glass Christmas trees.

Consumers, including Edmonson, say they’ve been largely unsuccessful in getting refunds from PayPal. Some have said PayPal has simply encouraged them to work it out with the vendor. Others have been promised a refund if they themselves send the package back on their own dime—but shipping to China can cost more than the original order itself.

“This is not an issue we are seeing on a large scale,” a PayPal representative wrote in an email to TIME. “At PayPal, we have a zero tolerance policy on our platform for fraudulent activity, and our teams are working tirelessly to protect customers against anyone attempting to defraud well-intentioned individuals.”

Complaints on PayPal’s own website, however, suggest otherwise. One thread regarding the PayPal account “Garland Information Technology Co., Ltd.” has dozens of messages over three months from people saying that they had ordered items, from hydraulic jacks to baseball bat decanters to Pimentel’s Christmas trees, that never arrived. “Can’t PayPal do something? A fraud is being perpetrated, perpetuated, aided and abetted,” wrote one user.

It’s difficult to follow the money trail from PayPal to actual people. Scam sleuthers have found that many of scam websites have links to companies in Britain, where lax government rules allow for dodgy shell companies to be created for dirt cheap. The scams websites’ filings on the country’s corporate registry Companies House have all sorts of minimal or misleading details, like repeating names or addresses of shared rentable office spaces. “It’s kind of like musical chairs: you see the same names popping up over and over,” Marissa Hadland, who has been investigating scam networks, says. “This one is a director for this company. They resign and then are a director-shareholder for this other company.”

But there are public links between one scam network and two legitimate Chinese companies: TIZA, which is focused on providing industrial Internet IT services; and TIZA’s subsidiary Youkeshu, a cross-border e-commerce company which sells goods through AliExpress, Walmart, Amazon, and other corporations. According to public records, Youkeshu is the biggest shareholder of both Shenzhen Guiguyun software technology co., LTD—which owns the domain Kokoerp.com, where many of the scam sites appear—and Duo Tongguang Electronic Commerce Co., Ltd, a shell company that has been the subject of hundreds of complaints on PayPal and in other reviews. Email addresses and internal portals link the Youkeshu and Kokoerp domains together. And some “Kokoerp” scam victims have reported receiving boxes with YKS—Youkeshu’s trading symbol—on the return label.

Moreover, Xiao Siqing, the chairman and CEO of TIZA, is publicly listed as the CEO of Youkeshu and the legal representative of Guiguyun. Since 2017, when Duo Tongguang was incorporated, TIZA’s revenue has increased almost fourfold, to more than half a billion dollars in 2019. A representative for Youkeshu declined to comment. A representative for TIZA did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The Fight Against Scammers Continues

Given the sprawling global nature of these scams, it’s extremely difficult for local police precincts to investigate and prosecute them. This disconnect led to ECommerce Foundation and other organizations to launch the first Global Online Scam Summit in November, with representatives from Interpol, Europol and the FBI tuning in. There, several people in positions of power pledged to invest more resources into fighting online scams: Hui Ling Goh, counsel for international consumer protection at the FTC, said that the FTC is in the process of developing a website for consumers to report international scams.

Abraham, at the ECommerce Foundation, says that the problems will only get worse unless there is concerted and swift collaboration amongst international and national law enforcement. “Europol and Interpol are just at the start of fighting scams,” he says. “My fear is that consumers will get scammed a lot more in the next few years.”

Meanwhile in the U.S., the issue has stalled in Congress. There has been much public debate about Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which shields social media platforms from legal responsibility for certain actions by their users. Both President Trump and President Elect Biden have excoriated the law, calling for it to be repealed or revoked. But Democrats and Republicans are divided on how to change it, meaning very little substantial progress has been made.

In April, Illinois Representative Adam Kinzinger introduced two pieces of legislation on the House floor with the goal of curbing fraudulent activity on social media. But he has also received very little support from his colleagues, and the bills have stalled. “It’s been really difficult. People are happy to complain about the issue, but when you put forward a solution, they don’t jump on,” Kinzinger tells TIME. “Writing the social media bill took us a year because we were trying to find consensus, and we just couldn’t get there. Anything with information and privacy has been really hard in Congress. There are too many layers to it.”

So until any movement happens, it’s up to the individuals who are getting scammed to fight the fight alone. Edmonson, in Texas, has filed several complaints with Paypal, and was told that the vendor could refund him $8. Pimentel is still overwhelmed complaints and queries, and her trees are still circulating the internet—not only on Facebook, but now eBay, Walmart, Pinterest and Amazon. And many of those ads can be traced back to the Kokoerp network.

Pimentel says that just this week, she was cold-called by a woman in Denver who pled for a refund on behalf of her 76-year-old mother who had fallen for a fake ad. “These poor women are being screwed,” Pimentel says. “I feel violated, exploited and impersonated—and these companies are allowing me to get beat up and ruined.” — with reporting by Charlie Campbell/Shanghai

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com