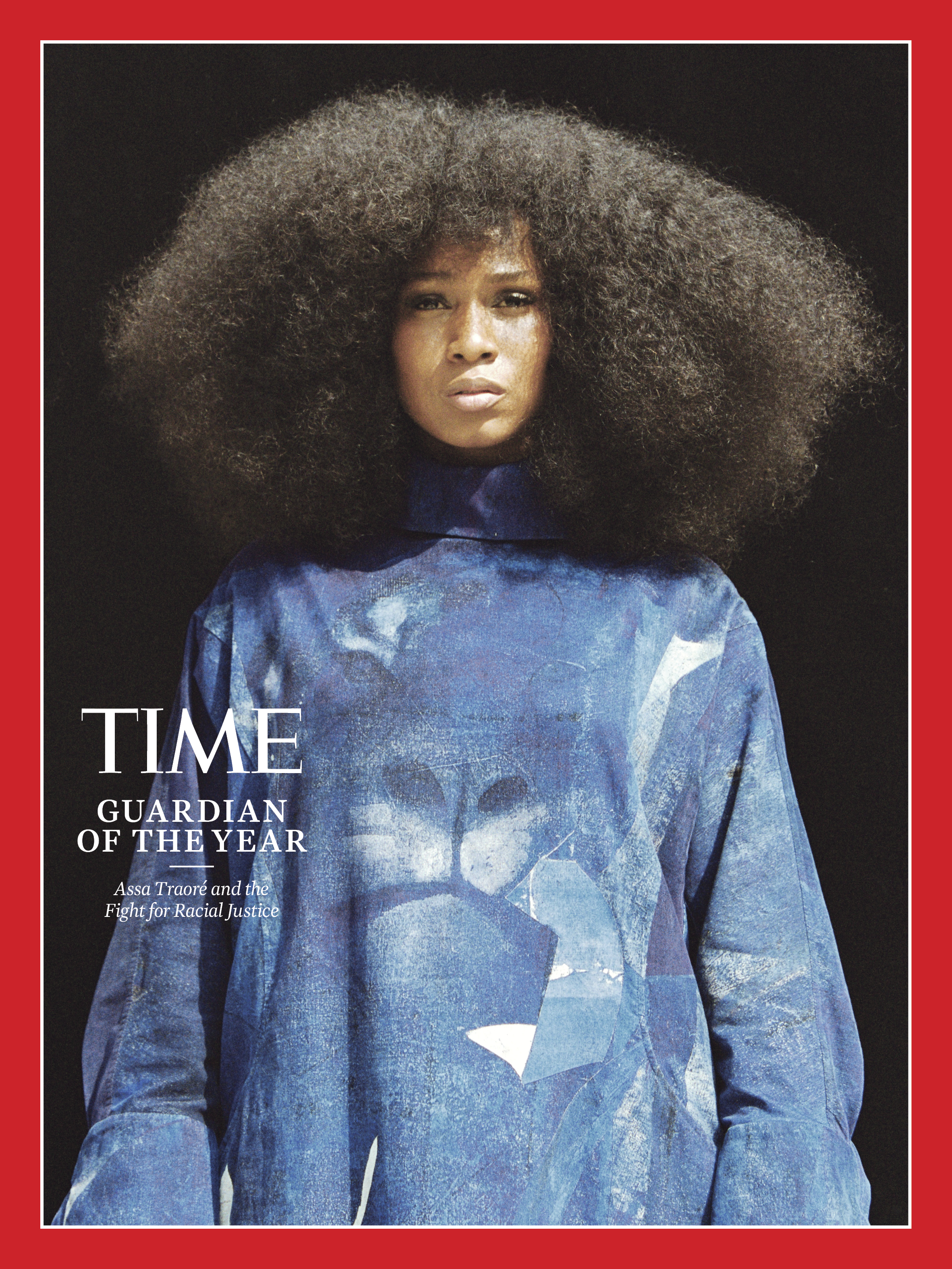

In May the videotaped death of George Floyd, pinned to the ground by police gasping “I can’t breathe,” was watched by millions worldwide in horror and revulsion. Assa Traoré, named one of TIME’s 2020 Guardians of the Year, could not bring herself to join them. Her younger brother Adama also died in police custody, in 2016, reportedly uttering those same dying words. “Imagining the same thing happened,” Traoré says, “it made it impossible to watch the final seconds of George Floyd’s life.”

Floyd’s words became Traoré’s rallying cry. On May 29, as the video of Floyd’s killing went viral, French authorities released a report clearing the three officers involved in Adama’s death of wrongdoing. Traoré’s group, Truth for Adama Committee, announced a mass protest, even though France was only just emerging from a two-month coronavirus lockdown. The following day tens of thousands of people poured into the streets, with banners showing the faces of Floyd and Adama, side by side.

After years of campaigning for justice in her brother’s death, Traoré says she believes there is now a far broader movement over police violence. “All the French people were there on the street,” the 35-year-old says, sitting in her living room on the eastern edge of Paris. “The Adama generation is on the street to speak out against police brutality, racial discrimination.”

Adama was arrested in July 2016 after trying to flee from police while they were looking for one of his brothers. Unlike in Floyd’s case, his death was not documented on film. The official autopsy concluded he had died of heart failure, but two medical reports commissioned by the Traoré family pointed to rough treatment, finding he was asphyxiated by police subduing him. French police rejected that conclusion, but the campaign to determine the truth continues. On Dec. 1, a Paris court struck down one of the official reports that backed the police version, after the Traores’ lawyer pointed out procedural flaws. A new report from Belgian medical experts is expected in January.

Traoré says Adama’s death shattered their Malian-French family, especially the 16 surviving siblings. “We did not even have time to cry. I vowed then and there that my brother’s death would not become a minor news item,” says Traoré, who abandoned her job as a special-needs teacher to become a full-time activist. “We were going to fight.”

Just as this year has brought a reckoning over race in the U.S., so it has in France, where young Arab and Black men are 20 times as likely as white men to be stopped by police. As the protests have gathered pace, Traoré has become the most visible leader of the movement against racial injustice, a constant presence at marches, with one fist raised in protest. “She is playing with the imagery of the U.S. in the 1960s,” says Paris civil-rights attorney Slim Ben Achour. “She is an icon, there is no doubt about that, at the center of attention for people who cannot speak.”

Traoré says the reality for many Black people in France is drastically at odds with the country’s public image, of a nation that cherishes the concepts behind its motto, “liberté, egalité, fraternité.” Those words, “liberty, equality, fraternity,” seem hollow for many, she says. “When we draw back the curtains, horrible things are happening.” Exacerbating that is an official policy of equality that forbids the collection of race-based data, which many believe has left systemic racism unreported and unexplored.

The same day TIME visited Traoré, a security-camera video posted on social media showed police officers beating a Black music producer in Paris inside his studio. The outrage was instant, heightened by anger over proposed legislation that seeks to limit the ability to distribute images of police in action. On Nov. 26, France’s interior minister ordered the officers suspended. Two days later, some 40,000 people protested in Paris, with Traoré on the front line.

Having forged a wide movement from an intimate tragedy, Traoré now faces a choice of how to try to harness the mass anger. To some allies, one path seems clear: A political career, and perhaps a run for France’s parliament. “I always try to convince her to do that,” says Geoffroy de Lagasnerie, a left-wing academic who co-authored a book with her last year on Adama and police tactics. “She would be a terrific politician. She has a kind of capacity to submit the institution to her will.”

Assa Traoré remains hesitant. Her campaign has “a power that [politicians] don’t have,” she says. “That power is to go on the street.” Still grieving her young brother, she says that grassroots activism will remain her role for now. Since Adama’s death, she has met with activists around France, piecing together a protest movement with her family loss at its center. “We have to get through that fight,” she says. “Then we will see what is going to happen.”—With reporting by Ciara Nugent/London

This article is part of TIME’s 2020 Person of the Year issue. Read more and sign up for the Inside TIME newsletter to be among the first to see our cover every week.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com