We are at war with a virus that is currently winning by taking two 9/11’s worth of victims every week—by Christmas it could be three. There is no question that if 1,000 Americans were dying each day in a war, we would act swiftly and decisively. Yet, we are not. This should not be about politics—it is about human beings—and we should be acting like it.

So far, the U.S. government has put most of our eggs in the vaccine basket, and despite the vaccine always being “one more month away,” we have a long road ahead before a vaccine is safe, effective and, most crucially, widely available. To win the war on COVID-19, we need a multi-pronged public health strategy that includes a national testing plan that utilizes widespread frequent rapid antigen tests to stop the spread of the virus. We need to think strategically and creatively, be bold, and most importantly, not allow the perfect to be the enemy of the good.

Widespread and frequent rapid antigen testing (public health screening to suppress outbreaks) is the best possible tool we have at our disposal today—and we are not using it.

It would significantly reduce the spread of the virus without having to shut down the country again—and if we act today, could allow us to see our loved ones, go back to school and work, and travel—all before Christmas.

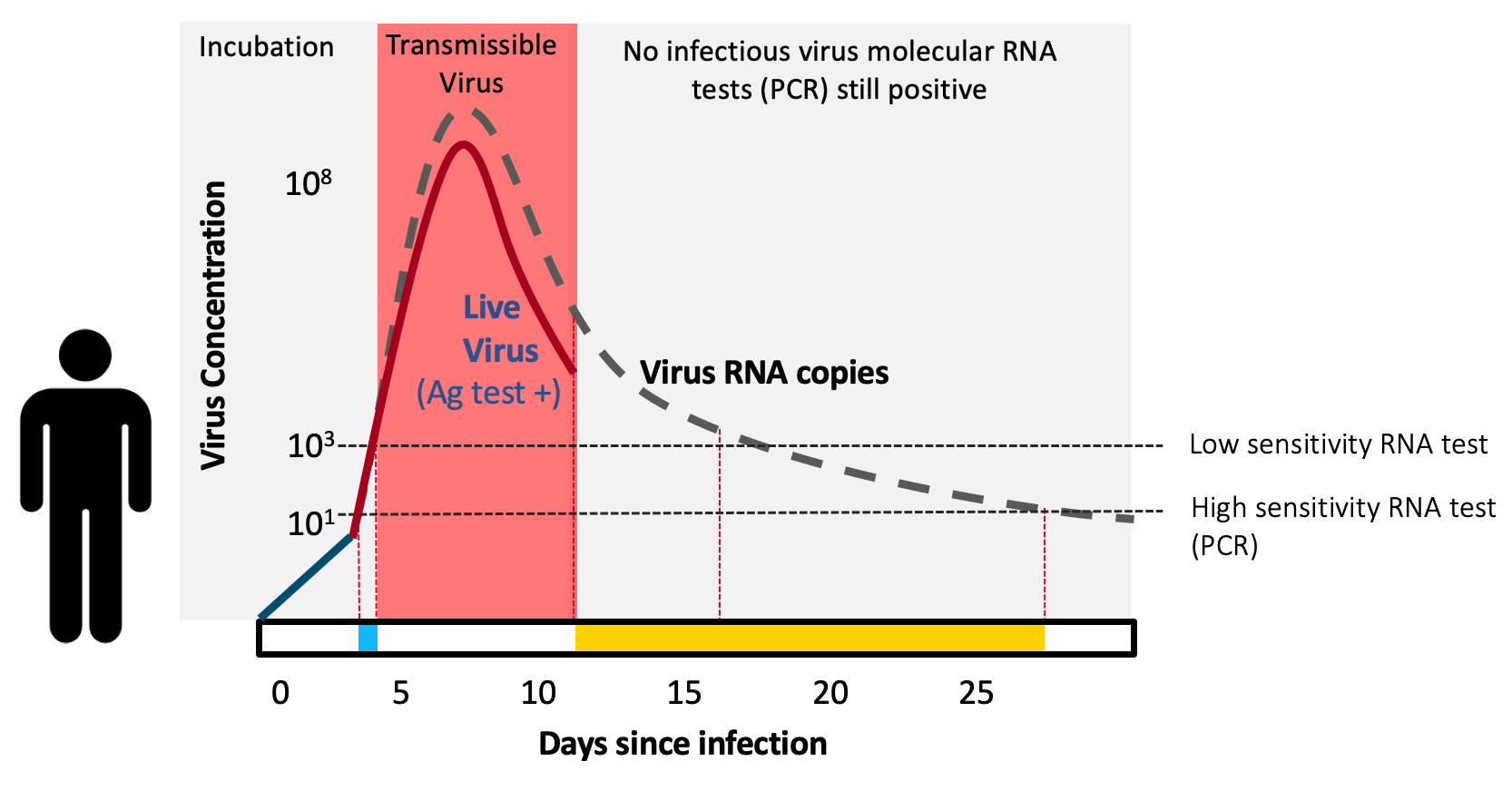

Antigen tests are “contagiousness” tests. They are extremely effective (>98% sensitive compared to the typically used PCR test) in detecting COVID-19 when individuals are most contagious. Paper-strip antigen tests are inexpensive, simple to manufacture, give results within minutes, and can be used within the privacy of our own home—the latter is immensely important for many people across the U.S.

The leading prototype for the antigen test I’m describing includes a small paper strip with a special molecule embedded on it that detects SARS-CoV-2 and turns dark when the virus is present in the sample. To use the test, the person gently swabs the front of their nose. They put the swab into a small pre-filled tube and drop a paper strip into the tube. Within minutes, the results are known based on whether a line shows up on the paper or not (much like a pregnancy test).

If only 50% of the population tested themselves in this way every 4 days, we can achieve vaccine-like “herd effects” (which is when onward transmission of the virus across the population cannot sustain itself—like taking fuel from a fire—and the outbreak collapses). Unlike vaccines, which stop onward transmission through immunity, testing can do this by giving people the tools to know, in real-time, that they are contagious and thus stop themselves from unknowingly spreading to others.

The U.S. government can produce and pay for a full nation-wide rapid antigen testing program at a minute fraction (0.05% – 0.2%) of the cost that this virus is wreaking on our economy.

The return on investment would be massive, in lives saved, health preserved, and of course, in dollars. The cost is so low ($5 billion) that not trying should not even be an option for a program that could turn the tables on the virus in weeks, as we are now seeing in Slovakia—where massive screening has, in two weeks, completely turned the epidemic around.

The government would ship the tests to participating households and make them available in schools or workplaces. This program doesn’t require the entire population to participate. Even if half of the community disregards their results or chooses to not participate altogether, outbreaks would still be turned around in weeks. The point is to use these tests frequently so people are likely to know their status early, before they transmit to others. It is frequency and speed to get results, and not absolute sensitivity of the test that should take center stage in a public health screening program to stop outbreaks.

With antigen testing, specificity (or potential for false positives) are important to consider and can be easily solved by including a second confirmation test to confirm original positive test results. With every pack of 20 paper strip tests sent to a household, three additional confirmatory tests would be included. When you test positive, you immediately use a confirmation test at home, and if you confirm positive, you stay home and isolate. If negative on the confirmatory test, you test again the following day to be sure.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests has been a central debate – but that debate is settled. People have said these tests aren’t sensitive enough compared to PCR. This simply is not true. It is a misunderstanding. These tests are incredibly sensitive in catching nearly all who are currently transmitting virus. People have said these tests aren’t specific enough and there will be too many false positives. However, in most recent Abbott BinaxNOW rapid test studies, the false positive rate has been ~1/200. Addition of the confirmatory rapid tests to each household’s packet can bring the specificity to >99.9%, and higher if those confirmatory tests leverage the more specific (but much more limited supply) rapid soon-to-be at-home PCR-like tests that are on the immediate horizon.

To ensure adoption, testing will be exceedingly convenient and reporting would be voluntary, with the click of a smartphone button or text message. To stop COVID-19 we need to put the public back in public health and we need to focus on meeting the people where they are at. After almost a year, the public is exhausted and, rightly so. Shutdowns, economic turmoil, sickness and death, and living in constant fear of an invisible virus is tiring.

To make any program work today, it must be on the people’s terms. Thus, we should bring the test to the people and we should be working with the companies that reach into nearly every single household in America, such as AT&T, Verizon, Apple, Google, Facebook and Amazon to figure out the easiest “one-click” reporting tools that anyone can use. Reporting a fraction of a massive number of tests will ultimately give more information, not less, to the public health authorities. We should also hire, at whatever cost, Coca-Cola’s best marketing agencies to figure out how to get the best messages across and ensure that everyone in this country understands how to use the test and how to interpret it. Simply put, we need all hands on deck—not just the scientists—and we need to meet people where they are.

Contact tracing needs would be minimal because the population will already be testing themselves regularly. One of the major reasons for contact tracing is to trace contacts and ask them to get tested. Usually this is just once and with testing delays and low access to testing it is usually too late anyway. In public health screening using widespread rapid testing, people won’t need to be traced and asked to test in order to know if they are infected. They will already be testing. Because testing will be twice per week, contacts will figure out if they are infected much earlier than they would through a test-trace and isolate contact-tracing program—which, despite being cornerstones of our national efforts to date, have largely failed to control the virus in the U.S. except when the associated testing was very frequent. Importantly though, frequent rapid testing should not necessarily replace test-trace and isolate nor other mitigation strategies, but can exist in parallel

To catch infectious people, rapid antigen tests work in asymptomatics as well as they do in symptomatics. A public health test doesn’t care about symptoms, it cares only about detecting virus—and if someone is very infectious, the virus will be there, detectable by the test—regardless of whether the symptoms are. Reports have caused confusion stating that rapid antigen tests do not work as well in asymptomatics—this is a myth. The confusion is when antigen tests are compared to PCR. The PCR test detects virus RNA—which exists during the week or so of contagious infection, but also lingers in the nose for weeks or sometimes months afterwards (which is why the CDC recommends against testing for 90 days after recovering from infection). Unlike PCR, antigen tests detect live virus, not just the virus’ genetic material. So antigen tests are actually meant to disagree with positive PCR results as soon as the person is no longer contagious. This also implies that antigen tests may even be more accurate than PCR, not less, when the goal of testing is to screen seemingly healthy people for presence of live, contagious virus.

Do these tests exist today and if so, why aren’t we using them already?

The antigen test technology exists and some companies overseas have already produced exactly what would work for this program. However, in the U.S., the FDA hasn’t figured out a way to authorize the at-home rapid antigen tests because the FDA is used to regulating medical devices, not public health screening tools. Thus, every test that is authorized, regardless of whether it is designed for medicine or public health, is authorized as a clinical medical device. Requiring public health tools to meet medical device specifications has caused company after company to delay their FDA submissions in a never ending attempt to meet the FDA’s guidelines—for example the need to separately qualify a rapid antigen test for symptomatic versus asymptomatic use. This slows development and authorization because it is hard to find asymptomatic people when they are contagious (i.e. when the antigen test is meant to be positive) in order to gain an asymptomatic medical claim. Requiring public health tools to get funneled through a medical diagnostic authorization process also runs the risk of diluting down the test metrics that medical diagnostics demand—which again, are distinct from the public health tests we need today.

The FDA’s persistence to authorize needed public health tools only as medical diagnostics is causing massive confusion among physicians, public health leaders and our state and national governments. We must immediately stop attempting to solve a public health problem by focusing on it as a series of independent medical problems needing to be fixed. We need to create a new authorization pathway within the FDA (or the CDC) that can review and approve the use of at-home antigen testing, without these medical-centric barriers. We need to be innovative and creative with how we make this work especially since we are in a “war-time” situation where this virus will not wait for us to navigate a bureaucracy.

Masking and social distancing aren’t widely adopted, so why would people comply with this program? We believe that a simple, at-home (or school / work) testing program where results are known within minutes and people can choose to participate or not, and choose to report their results will be widely adopted across the United States. Simply put, people want to know if they, or their household members are infected and, importantly, infectious. Once infected people can test during isolation to potentially cut the isolation time to only those days when the antigen tests read positive, plus an additional day, or two negative tests 24 hours apart to be safe, reducing the burden on the individual (especially asymptomatics) and helping the economy. For people who really cannot or refuse to isolate for long, even a 2-3 day isolation after becoming antigen positive might still prevent the bulk of transmission.

At-home testing is not a publicly visible action. It is as private as brushing your teeth in the morning. Yet it will give even the most ardent anti-masker critical information about their status, which will help them make responsible choices for their family, friends and community members, and immediately help reduce the rate of virus transmission. Even if people do not isolate entirely, we believe that, upon receipt of a positive result, most adults will choose to modify their behavior to avoid getting their loved ones sick.

Unlike vaccines, these tests exist today—the U.S. government simply needs to allocate the funding and manufacture them. We need an upfront investment of $5 billion to build the manufacturing capacity and an additional $10 billion to achieve production of 10-20 million tests per day for a full year. This is a drop in the bucket compared to the money spent already and lives lost due to COVID-19.

With a group of Harvard economists, we recently evaluated the financial costs and gains of a nationwide antigen testing plan that would have started in June 2020 and run through December 2020. The total cost (all included) was $28 billion, it would have increased GDP (conservatively) by $395 billion and possibly $1 trillion or more if we did not have the outbreaks that we do today and did not need to shut down again. We found that it would have saved greater than 100,000 lives. There is no question that investing in rapid antigen testing now can have major economic benefits over the next six months and especially in the lead-up to a safe and effective vaccine.

Why hasn’t it been done in the U.S.?

When pushed to try this type of program, with all the evidence laid out, our nation’s leaders have demurred, suggesting an FDA regulatory landscape that is too difficult, or have simply refrained and asked: why hasn’t anyone else tried this yet? It appears our leaders are failing to understand that we are living history, today, and it is they who must be the leaders to try bold new agendas.

A large and organized deployment of rapid paper-strip tests can enable the United States to begin to achieve normalcy within weeks—we just need to start now. Countries like Slovakia and the United Kingdom are currently utilizing mass rapid antigen testing programs and already seeing great success. We can take their models a step further, deploy a nation-wide large-scale effort, and demonstrate to the world how the United States will win the war against COVID-19.

To learn more about Dr. Mina’s plan and get involved with the effort, please visit rapidtests.org

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com