At her White House swearing-in, the week before Election Day, the newest Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett said that she would discharge her duties impartially, and not in accordance with her personal policy preferences. History, however, suggests that this is doubtful. It is more than coincidence that the “conservative” justices now on the court have all been appointed by Republican Presidents, and “liberal” justices by Democrats. For all the perennial talk about the judicial branch being above politics, such has never been the case—and that past offers a hint about what it might be reasonable for Joe Biden and a Democratic Congress, if elected, to do about the makeup of the Supreme Court.

If President Donald Trump wins the election, the partisan nature of the Court will be one more reason for him to be happy: With Barrett the youngest justice, at just 48, the conservative direction of the Court will be assured for a generation. But if the Democrats win, national attention will likely turn again to the fact that that, while federal judges are appointed for life—that’s in the Constitution—the size of the Court is up to Congress, and in fact changed seven times in the nation’s early history.

During the campaign season, Biden has been reluctant to say whether he would “pack” the Supreme Court. This is understandable. The phrase “court packing” is a pejorative—stacking the deck, changing the rules. But, the deck is already stacked against the political preferences of a majority of Americans: 2004 is the only year since 1988 when the Republican nominee won the most popular votes in the Presidential election. Yet, Republican presidents have appointed 6 of the 9 sitting Supreme Court Justices. And acting to get the highest court in line with national preference, as expressed by the vote, would be both politically appropriate and historically coherent.

This is not the first time in the Court’s history that Congress has considered altering its ideological composition. The original Judiciary Act of 1789 pegged the number of justices at six. When the Federalists were defeated in 1800, the lame-duck Congress contracted the size of the court from six to five—spitefully, to deprive Democratic-Republican President Thomas Jefferson of an appointment. The incoming Democratic-Republican Congress repealed the Federalist legislation, and increased the roster to seven to give Jefferson an additional appointment. In 1837, the size was enlarged to nine to give patronage-hungry Andrew Jackson two more appointments. When a Democrat, Andrew Johnson, became president upon Abraham Lincoln’s death in 1865, a Republican Congress voted to reduce the size to seven (achieved by attrition) to guarantee Johnson would have no appointments. After Ulysses S. Grant was elected in 1868, Congress, to give Grant two new appointments, restored the court to nine, where it stands today.

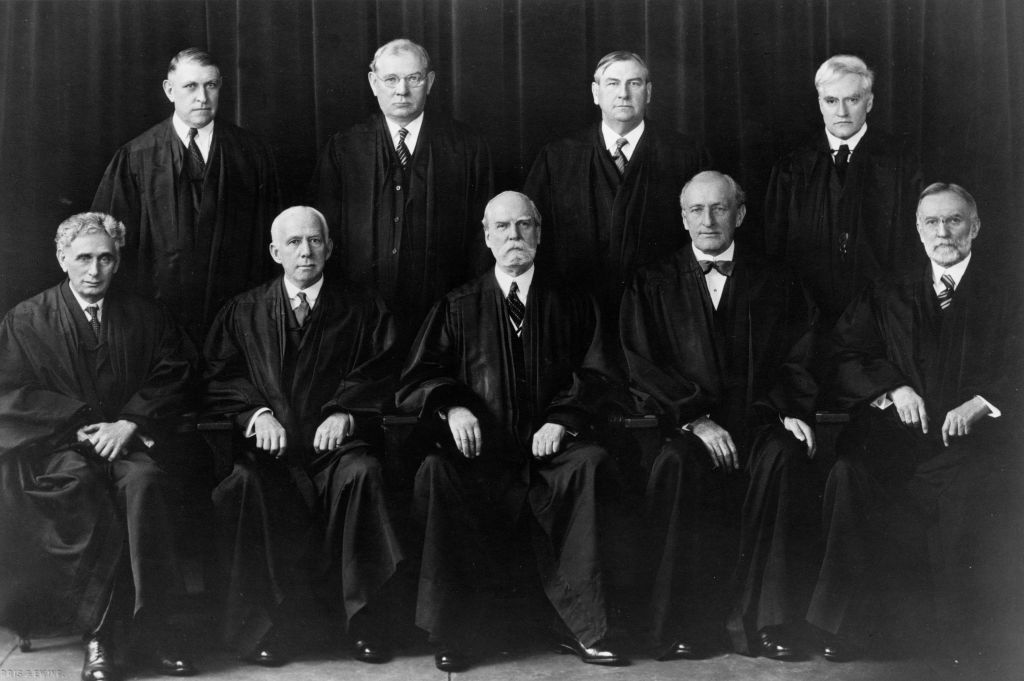

Perhaps most famously, Franklin Delano Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937. The justices were deprecated by their detractors like columnist Drew Pearson as “nine old men,” and FDR believed they needed to get in line with public opinion. In March 1937, when five conservative justices repeatedly struck down his progressive New Deal legislation, an angry Roosevelt took the nation into his confidence in a “Fireside Chat,” and said he needed to “save the Constitution from the Court, and the Court from itself.”

His ringing words: “This plan of mine is no attack on the Court; it seeks to restore the Court to its rightful and historic place in our constitutional Government, and to have it resume its high task of building anew on the Constitution ‘a system of living law.’”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

His plan involved the introduction of a bill, known as the Judicial Procedures Reform Act, providing that the President would have the power to appoint one justice for every member of the Supreme Court over the age of 70 up to a maximum of six additional justices.

The court-packing bill was dead on arrival in the Senate. Senators of Roosevelt’s own party did not like court packing, and the measure was tabled. But Roosevelt made his point. The bill exerted political pressure on the Court. One of the conservative justices, Owen Roberts, did a stunning about face, and voted with the liberals in the West Coast Hotel case, which 5-4 upheld a Washington state minimum-wage law. This was known waggishly as the “switch in time that saved nine.” Though some historians argue that Roberts’ switched vote had nothing to do with Roosevelt’s proposal, no matter. Eventually, the five conservative justices died or retired. FDR got to appoint nine liberal justices during his presidency.

The Democrats will likely be out for blood if they take the Senate and keep the House, which has become increasingly likely. Their leader Senator Chuck Schumer has already announced that “everything is on the table.” Court packing might seem politically unpalatable, and might only exacerbate the problem if Republicans countered when the political pendulum next swung right. But a Democratic majority in Congress has other options.

For example, they could implement a policy—without changing the constitutionally mandated life tenure of the federal judiciary—under which justices would rotate off the Supreme Court to temporarily take seats on the lower federal courts. Another possibility, proposed by the late Cornell Law School dean Roger Cramton in 2005, would be to impose 18-year term limits on Supreme Court justices, getting around the need for a Constitutional amendment by declaring that, instead of retiring, the former justices would instead be on stand-by to fill in if another justice dies or recuses herself, and would have the option to serve as senior justices on the lower federal courts. Court packing? All depends on how you look at it.

More than a century ago, the humorist Finley Peter Dunne quipped sarcastically that the “Supreme Court follows the election returns.” The line is often cited with a wink of the eye about how easily the court can be swayed; now, however, the court is out of step with majority opinion—and if Biden wins, will be likewise off the mark on the election returns.

What happened in the 1930s could happen again: some of the other “conservatives” may switch, and vote with the liberals on the key cases. We will have to see. This is not 1937, but we are again living in troubled times—and if extraordinary measures are needed to make Dunne’s quip be taken seriously, those measures will be well in keeping with the court’s history.

Historians’ perspectives on how the past informs the present

James D. Zirin, a former federal prosecutor, is the author of Supremely Partisan, a book about raw politics and the Supreme Court.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com