As more and more people are diagnosed with COVID-19, the question of how long immunity to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the illness, lasts, is increasingly important. Understanding that would help patients know whether they can get re-infected, and potentially even help doctors to better understand what type of protection we can expect from vaccines.

Previous research found that levels of antibodies in recovered patients start to wane about three months from when those patients first experience symptoms. But in a study published in Science this week, researchers at Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai report that antibodies may last as long as five months.

The scientists analyzed blood plasma, which contains immune cells including antibodies, from more than 30,000 people who were sick with COVID-19 between March and October. The majority of recovered patients experienced mild to moderate symptoms and weren’t hospitalized. They donated their plasma as part of the hospital’s study of whether this plasma, enriched with immune cells, could be used to treat coronavirus infections. Nearly half of them generated high level of antibodies.

To get a better idea of how long the antibodies last, the researchers focused on a smaller group of 121 participants and measured their antibody levels several times: starting a month after they first experienced symptoms, then again at 52, 82 and 148 days. They found substantial levels of antibodies in most of the participants all the way to the end of the study. What’s more, these antibodies continued to neutralize SARS-CoV-2 at pretty much the same levels in the lab throughout the five months.

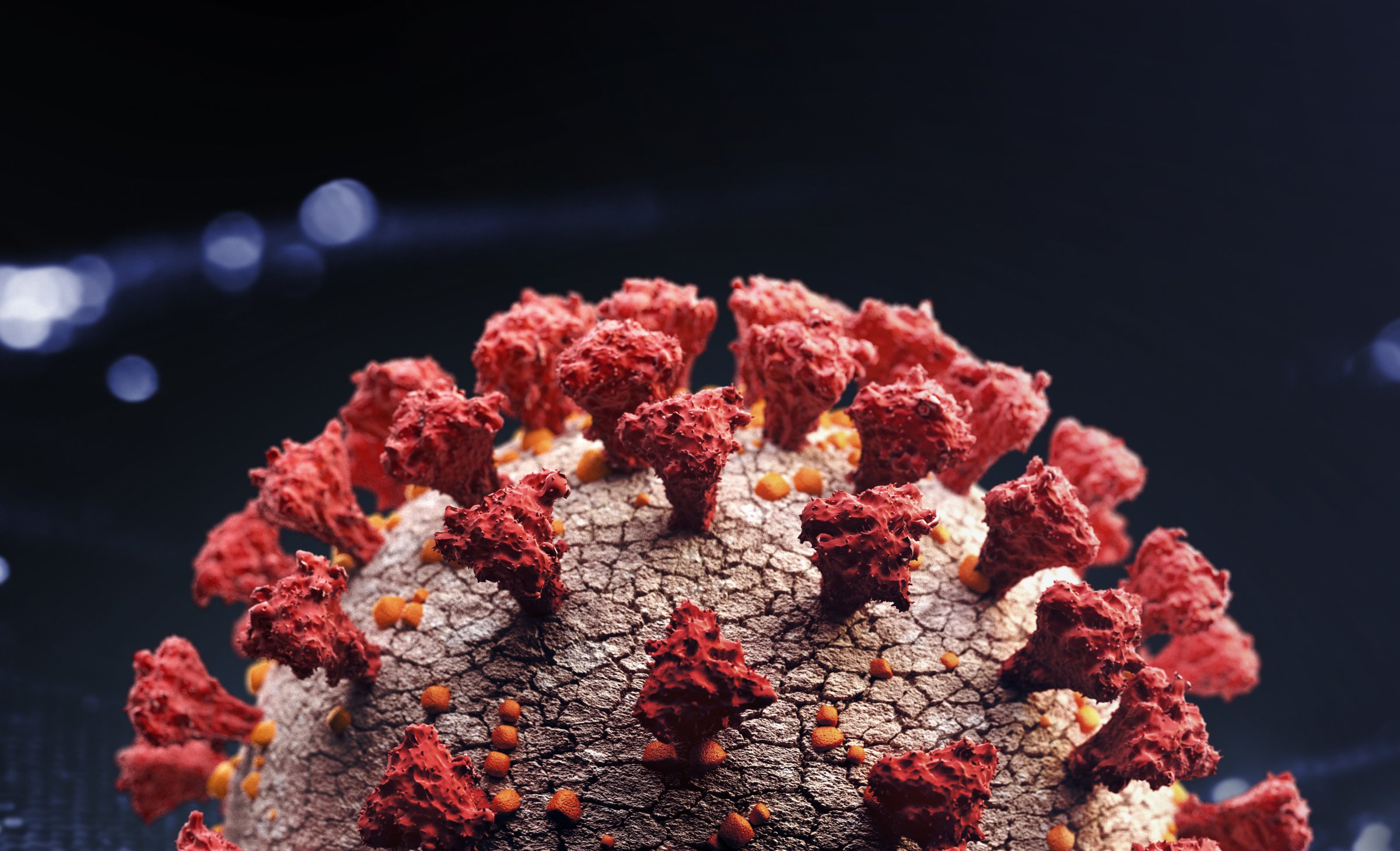

Ania Wajnberg, associate professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai and leading author of the new paper, says that the reason why she and her team found consistently robust antibody levels for longer than previous studies may have to do with the test they used. It was developed at Mt. Sinai and is specific to a portion of the coronavirus spike protein that’s a particularly attractive target for the immune system—“the body produces a lot of antibodies to that area,” she says. Other researchers may have used different assays for detecting antibodies that might be directed at different parts of the COVID-19 virus, which, she says, may wane more quickly.

Her team was also able to analyze the types of antibodies they found over time, which may help explain why they were able to pick up antibodies for a longer period of time. The antibodies they collected from people soon after their recovery included IgG antibodies, which circulate in the blood and generally decline in number after about a month since they are designed to quickly respond to new viruses. On the other hand, they also found antibodies that remained at the five month mark—these antibodies are most likely made by immune cells in the bone marrow whose job is to keep the immune system supplied with the right defensive cells over the long term, based on whatever viruses or bacteria the body has recently seen. It’s possible that once these bone marrow-based cells are involved, the level of antibodies could remain stable for several months.

Exactly how long these antibodies may remain to protect against infection isn’t clear yet, but Wajnberg plans to continue collecting plasma and analyzing the antibodies in the smaller group of donors for a year. If the antibody levels remain stable, that’d be a sign that recovered patients do likely develop a high level of immunity from the virus—and it bodes well for the efficacy of future vaccines. “Presumably if there is longevity of these antibodies after infection, that is good news for a vaccine,” she says. “But we don’t know how much longevity yet. We just need to follow these people for more time.”

However encouraging the results are that some type of immunity against the COVID-19 might be possible, Wajnberg warns that people who have recovered from infections should still take precautions. “This is a large data set and the study is encouraging in terms of there being some protection in the majority of people who had SARS-CoV-2 infection in the past,” she says. “However, until we know more about what actually protects against the virus, we should still continue to follow all the recommended precautions around hand washing, masking and social distancing.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com