Emma remembers most of all the pressure in her chest as she struggled to breathe. For at least an hour, she and two other women were packed into a wooden box, one on top of the other like animals to slaughter, in the back of a truck as it crossed the border from Mexico into the United States. Her clothes were soaked through with sweat, her leg cramped from twisting to fit on top of the woman below, and her lungs ached from the weight of the woman lying above her. “I thought I was going to die,” she says, wiping away tears. Nearly a year later, the memory still makes her small frame recoil.

The 45-year-old never expected to end up trapped in an international human trafficking operation. Just a few weeks earlier, Emma had boarded a flight in Beijing that she thought would lead her to a new life in the U.S. The past few years had become intolerable for her in China. She’d fallen for a business scam, gotten into debt, and become the target of loan sharks, who dumped feces and animal blood at the beauty shop where she worked in Guangxi, China. They threatened her so often that she went into hiding at her sister’s house.

She’d applied twice for a tourist visa to the U.S., but was rejected, so she took an acquaintance’s advice and went to an office in the neighboring province of Guangdong. There, a man said he could help her. He told her that he could get her a Japanese visa that would allow her to enter Mexico, and that people there would then help her cross the border to the U.S. and find a job. To Emma, who had a high school education and did not speak English, the deal sounded like her best option, even if the details were sparse and the price was steep: the man was asking 200,000 yuan or nearly $30,000. “There’s nothing worse” than the life I’m living, she remembers thinking.

More from TIME

As it turned out, there was. After Emma arrived in Mexico in spring 2019, nothing went as she had expected. Her terrifying journey in the box in the back of the truck ended in Los Angeles and later, she was transported to Bowling Green, Ky., where she was tricked into working at an illicit massage parlor. Soon, she was being pressured by her boss to do whatever the customers asked for. She paid $10 a day to sleep on a single mattress on the floor in a back room of the parlor and cooked all her meals on a hot plate, constantly monitored by security cameras mounted around the store. Emma could earn tips by serving clients sexually, but otherwise she received only $20 of the $60 customers paid for her services.

Emma had no one to call for help. She knew nobody in the U.S., was unfamiliar with the immigration system, and she was terrified to stray too far from the massage parlor. Her boss had told her repeatedly that if American police saw her outside of the parlor, they would “execute” her. “You’re illegal. You’re like an ant,” Emma says her boss told her. “If you get killed by the police, nobody knows who you are anyway.”

In July 2019, Kentucky investigators raided the massage parlor where Emma was working and living. When they discovered her, she was so traumatized that she could not stop crying. But she answered all the questions local police and Kentucky state investigators asked and, later, she was connected with an organization that helps survivors of human trafficking. Advocates offered her safe housing, counseling and lawyers that would guide her through the steps required to remain legally in the U.S.

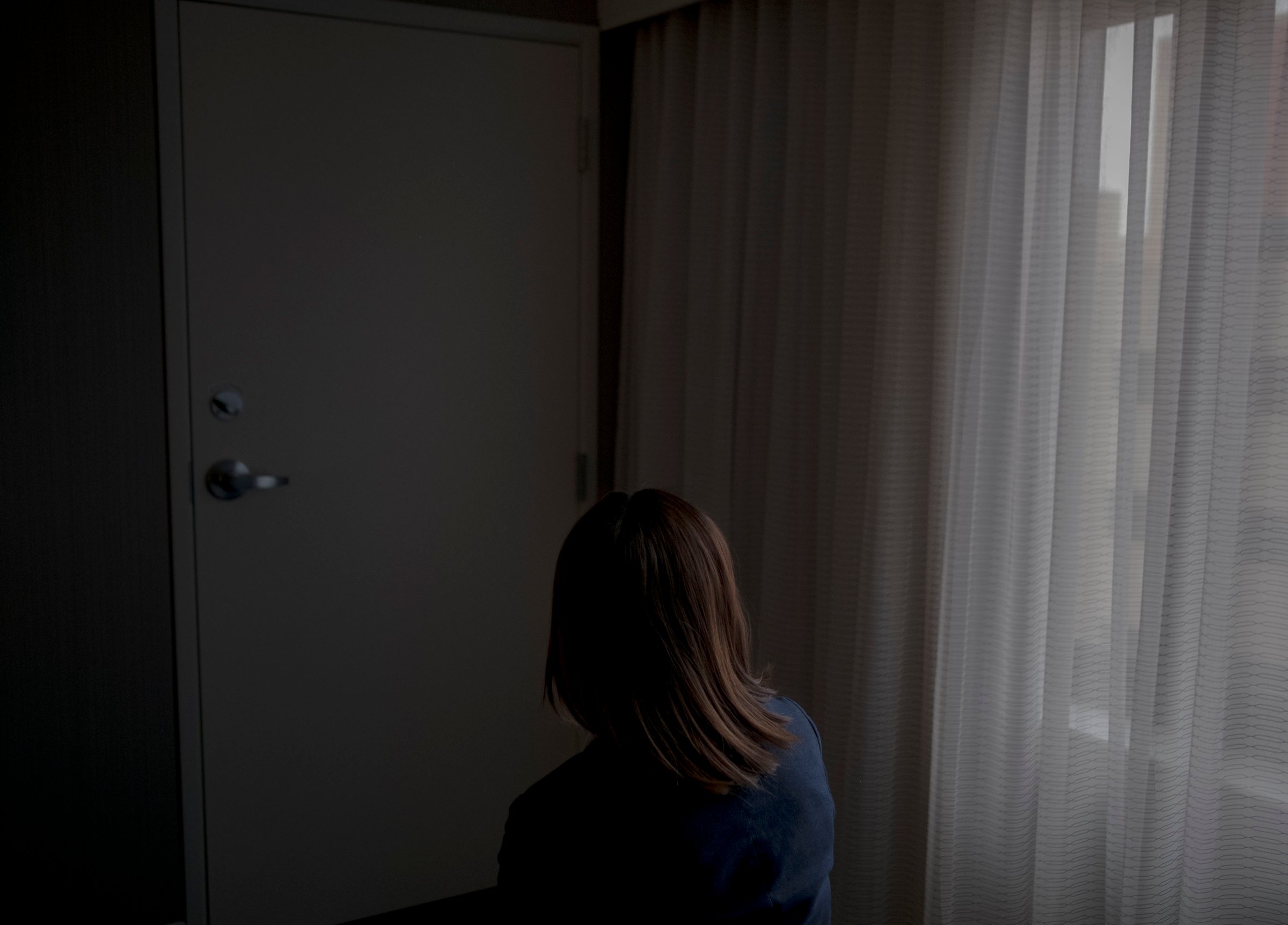

But more than a year later, Emma is still in limbo. The federal government hasn’t processed her application for a special visa meant for human trafficking victims and in the meantime, she has no legal status, no authorization to work, and must, by necessity, remain in the margins of society. Because of her vulnerable situation, she asked TIME to be identified as Emma, which is not her real name.

Emma’s experience has become increasingly common under President Donald Trump, who has put fighting human trafficking among his top priorities. His daughter and White House adviser Ivanka made the issue one of her key causes, giving it frequent White House attention, and just this month, the Department of Homeland Security announced it had launched a new Center for Countering Human Trafficking to bring together law enforcement officials and staff from across the agency to work on human trafficking investigations. In January, at a White House summit during “National Slavery and Human Trafficking Prevention Month,” Trump championed his Administration’s work. “I have never seen such enthusiasm for a single issue as I have for human trafficking,” he said.

Counter-trafficking lawyers, victim advocates, and former Trump Administration officials offer a starkly different perspective. They say that by cracking down on all forms of immigration, including legal and humanitarian avenues, the Trump Administration has made the work of preventing human trafficking more difficult in key and measurable ways. Specific policy changes across a variety of federal agencies, including the Departments of Homeland Security, State and Justice, have increased barriers to victim protections, complicated investigations into trafficking networks, and warped Americans’ perspectives of what the problem looks like. Those harms, counter-trafficking experts say, will be hard to reverse, even if Trump’s not reelected this year.

“What we’ll see is a decade of lost ground in addressing human-trafficking in the United States,” says Jean Bruggeman, executive director of Freedom Network USA, the country’s largest coalition of anti-trafficking service providers and advocates. “We’ve got at least four years, if not eight, of harmful policies that are making it easier for traffickers, pushing survivors further into the shadows and causing service providers who are most likely to be able to identify trafficking victims to not trust federal agencies.”

Bruggeman says she had been used to having good relationships with staff across the federal government. But under the Trump Administration, she found meetings were often one-sided; she and several other major anti-trafficking groups boycotted the January White House summit. Ultimately, she says, “this government has chosen to ignore the needs of survivors and to reward traffickers.”

Policy changes exacerbate the trafficking problem

Human trafficking is one of the world’s fastest growing criminal industries and one of the most difficult crimes to stop. It unfolds in the shadows, preys on victims who are already marginalized by society, and takes many, disparate forms. Polaris, an anti-trafficking group that operates the U.S. national human trafficking hotline, identifies 25 types of trafficking that span a wide range of industries, from restaurant and food service to factories, manufacturing, and beauty and illicit massage. Victims are recruited in a variety of ways as well. Most are recruited through intimate partners, by family members, or by someone promising a job that turns out not to be legitimate, according to data gleaned from Polaris’s help hotline.

Emma falls into that third category, and the nearly $3 billion-a-year illicit massage industry, where she ended up, is one of the largest and most networked trafficking markets in the U.S. There are more than 10,000 illicit massage businesses across the country, according to Heyrick Research, an intelligence-driven research organization focused on human trafficking. From the outside, these businesses look unremarkable. They’re often out in the open, in strip malls or on street corners, hidden by anodyne storefronts. But the sex work or forced labor that happens inside can be difficult for law enforcement to prove.

“Trafficking cases often include psychological coercion, threats of violence that are not written down,” Bruggeman says. “There’s not a large paper trail for a lot of this.”

In Emma’s case, her boss trapped her at the massage parlor not with physical shackles, but with fear of deportation or death. She told Emma that if she did not perform the sexual acts requested of her, the clients would call the police. Emma did refuse to engage in many activities, and some clients grew violent, pulling her hair, trying to force her to touch them anyway, or demanding their money back. When she complained, Emma’s boss suggested she move to another massage location in the area, a tactic that experts say traffickers often use to keep their illegal businesses from being detected. Investigators believe that Emma’s boss was involved with multiple illicit massage parlors and was part of a larger trafficking network. The investigation is ongoing.

For years, law enforcement officials nationwide have touted raids on illicit spas and massage parlors as part of the state and federal government effort to crack down on trafficking. The issue received renewed attention in February 2019 when Robert Kraft, the New England Patriots owner and Trump ally, was charged with paying for sex acts at a spa in Jupiter, Fla. But the charges against him were dropped this fall—an outcome that experts say is not uncommon. Raiding an illicit massage parlor is one thing; successfully prosecuting wealthy people who patronize the parlors, or even more crucially, the organizations who facilitate the trafficking, is the real challenge.

Overcoming that challenge often means that law enforcement officials must recruit the help of victims themselves. In many cases, only victims can identify the sometimes-vast roster of traffickers, including, for example, massage parlor managers, owners, and the teams of drivers and coordinators who transport workers between locations. “Law enforcement really depends on survivors being able to tell them what happened and explain where it happened and when it happened,” Bruggeman says. “Then they can find evidence to corroborate all of that.”

But convincing victims to cooperate with police or investigators is difficult. When police find potential victims, they are often terrified of law enforcement officials. That’s particularly true in instances where police are also charging the victims with other crimes, like prostitution or entering the country illegally. Even in cases where victims want to cooperate, they’re often psychologically traumatized, so it can take time for them to remember all the details of what happened to to them, experts say.

In 2000, Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA)—the signature federal legislation on human-trafficking—in part to address precisely this issue. One of the law’s key features was that it established a framework of “protection, prosecution and prevention”: the understanding is that law enforcement must protect and collaborate with survivors, rather than imprison or prosecute them, in order to prevent future trafficking. The T visa, which was created by the TVPA, was a crucial tool in this effort. It allowed noncitizen trafficking victims who were assisting law enforcement with an investigation to remain in the U.S. for a period of time with work authorization and benefits.

“In the years before the Trafficking Victims Protection Act was passed, trafficked clients, if I encountered them, they’d fall through the cracks,” says Kathleen Kim, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles and an expert on human trafficking. “There was no social safety net, there was no infrastructure to keep them afloat while advocates were working on their behalf to gain protection and benefits for them from the government.” The T visa also enables lawyers and advocates to help survivors transition to more stable environments, where they are less vulnerable to further exploitation.

These efforts to encourage human trafficking victims to cooperate with local, state, and federal law enforcement officials has been complicated by Trump’s immigration agenda. In November 2018, the Trump Administration announced that people denied a T visa may be issued a notice to appear in immigration court, beginning deportation proceedings. The move had an immediate chilling effect on human trafficking victims’ willingness to help police, lawyers and advocates say.

At the same time, the Administration made actually applying for or receiving a T visa even harder. Fee waivers on supplemental documents that used to be approved are now routinely denied, and applications are now adjudicated more strictly, multiple anti-trafficking experts and victims’ lawyers say. For example, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) now frequently requests further evidence that a person was indeed trafficked or that their trafficking history is the reason they are still in the U.S. Producing that kind of documentation can be nearly impossible for real human-trafficking victims, human trafficking experts say. Emma, for instance, has no written contract spelling out the intentions of the man at the Guangdong office or with the men who put her in a box in Mexico. When she arrived in Kentucky, she was paid in cash. The orders she received from her boss were verbal.

Daniel Hetlage, a USCIS spokesperson denied that requirements, eligibility criteria or the adjudication process for the T visa program had changed. “USCIS remains committed to protecting the integrity of our immigration laws and ensuring they are faithfully executed,” he said in a statement, adding that those denied T visas “may appeal adverse decisions.”

Advocates say the proof is in the numbers. The processing time for T visas has grown from an average of 7.9 months in 2016 to a current estimate of up to 2.4 years. The U.S. now has the largest backlog of pending T visa applications and the largest number of denials in the program’s history, as well as the lowest number of approvals in a decade, according to USCIS data.

Martina Vandenberg, founder and president of the Human Trafficking Legal Center, says the process of applying for a T visa was never seamless, but the past few years have been an anomaly. “Before we had six to 12 months to wait, but it was a waiting period that was tinged with hope,” she says. “Now it’s a waiting period tinged with fear.” Her organization informs trafficking victims that if they apply for, but are denied, a T visa they could be deported and then lets them decide how to proceed, she says. Since the Trump Administration’s 2018 policy change, her clients have chosen not to take the risk: she has not applied for a single new T visa in nearly two years. Without this protection, victims are better off simply disappearing into the country: without a path to legal status, employment, or benefits, why risk collaborating with law enforcement?

Those who work to counter human-trafficking say the Trump Administration has made their work more difficult in other ways, too. In 2018, the Justice Department released its applications for grants provided by the Office for Victims of Crime (OVC), but included new restrictions on how organizations could use that funding. Legal aid and victims service organizations that had previously used the OVC grants to help clear victims’ criminal records, for example, could still apply but would not be allowed to use funds for that purpose. Advocates say that prohibition was counterproductive: it had the effect of making victims even more dependent on those exploiting them. Traffickers often force victims to commit crimes and then use those criminal records as leverage: people with criminal records are much less likely to report crimes or cooperate with police, and if they escape their situation, they’re less likely to be able to find work, housing, or otherwise be able to live independently. This year, the OVC grants did not include the restriction on vacating criminal records, but the change was never explained, and advocates say other irregularities with the grant-making process continue.

“The Trump Administration’s immigration policies have made foreign trafficking victims’ lives more dangerous. Those policies have made it more difficult to escape. And those policies have made it more difficult to obtain relief,” Vandenberg says. “Trafficking victims are living in terror.”

Emma landed in the middle of this policy shift. In her case, the Bowling Green police, working with investigators from the Kentucky Attorney General’s Office, discovered her after the raid on the massage parlor. They contacted Kathy Chen, a contractor at Heyrick Research who served as an interpreter. Emma was terrified but determined to stop the people who had trafficked her, so she agreed to help the police. “What they always want to look for is, who trafficked you, who is behind this,” says Chen, of the investigation into Emma’s case. The Kentucky Attorney General’s office declined to comment on the ongoing investigation, but said that whenever it helps local law enforcement with sex or labor trafficking cases, its staff “undertake investigations from a victim-centered approach to ensure crime victims do not experience additional trauma.”

Emma later learned that law enforcement could help her apply for what’s known as Continued Presence, a status designed to help victims stay in the U.S. if they might serve as a witness in an investigation. She also applied for a T visa specifically for trafficking victims. In December, Emma’s request for Continued Presence was denied without explanation. Her T visa application is still pending.

Trump’s corrosive rhetoric

Since entering the White House, one of President Trump’s primary agenda items has been cracking down on people entering the U.S., both legally and illegally. As part of that effort, his Administration has ended Temporary Protected Status for hundreds of thousands of immigrants from countries with dangerous conditions; slashed the cap on refugees to a historic low; and forced asylum seekers to wait in Mexico.

But his influence has also been more subtle: he has distorted the national conversation about immigration by repeatedly caricaturing immigrants as gang members, criminals, and drunk drivers, while simultaneously promoting dramatic narratives about child sex trafficking, which play directly to Trump’s political base. Child exploitation has long been a particular concern among evangelical Christians, who have remained firmly in Trump’s camp throughout his time in office. More recently, the issue has served as a key force behind the rise of QAnon, the baseless conspiracy theory that claims Trump is fighting a deep state cabal of elites who are running a worldwide child sex trafficking ring. Trump has pointedly refused to condemn QAnon and at NBC’s town hall this month, lent credence to the group’s delusions, saying, “they are very strongly against pedophilia.”

Child sex trafficking is a real issue, but advocates say that the Administration’s rhetoric, backed with conspiracy-drenched claims, makes the actual work of preventing trafficking—of children and adults—even harder. Earlier this year, for example, QAnon believers, enthralled by a fictionalized threat, overwhelmed Polaris’ national trafficking hotline with calls about the false story that online furniture retailer Wayfair was trafficking children. The overwhelming volume of calls made it nearly impossible for Polaris to address and aid real victims in dangerous situations. In July, Polaris’s leadership grew so frustrated that it put out a statement encouraging people to “learn more about what human trafficking really looks like in most situations.”

Trump’s QAnon-fueled narrative, experts explain, has the effect of warping how people understand human-trafficking, making it harder for people to identify and prevent. “His emphasis on child sex trafficking occurs at the neglect of human trafficking at large and human trafficking as defined as a more complicated sociological phenomenon,” says Kim, the professor at Loyola Law School.

The narrow, fictional QAnon narrative also advances Trump’s incorrect suggestion that the victims of immigration crimes are Americans, and implicitly white, Kim says. Trump often conflates undocumented immigrants with traffickers and smugglers, and fans his supporters’ fears that their loved ones will be killed, raped or snatched away by a shadowy foreigner. That cartoonish narrative papers over a much more complex problem. There is no comprehensive national source of data on human trafficking victims, but experts say the majority of victims are recruited by people they know, and typically come from already vulnerable populations. People of color are disproportionately impacted by labor and sex trafficking, according to Polaris. “My concern,” says Kim, “is that the stronger the influence of QAnon becomes stronger the influence of white supremacy becomes.”

‘Stephen Miller won’t let it be solved’

People within the Trump Administration have raised similar concerns. Back in June 2018, when Elizabeth Neumann was the assistant secretary for threat prevention and security policy at the Department of Homeland Security, then-Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen tasked her with developing a new strategy on fighting human trafficking. When Neumann met with anti-trafficking groups and learned about the topic, she says it quickly became apparent to her just how much the Administration’s immigration posture was hampering the fight against trafficking. In particular, she says, the Administration’s goal of limiting overall immigration and Immigrations and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) intense focus on eliminating fraud, were creating a chilling effect on noncitizen human trafficking victims.

Neumann says she tried to raise the issue with policy officials at ICE, but the discussions didn’t go anywhere. She also tried to get recommendations into DHS’s strategy report on the topic, but when discussions became too heated, she settled for putting higher level language about victim-centered approaches in the strategy document. She figured she and the other officials would “fight all of this out” during the strategy’s implementation. But that never happened. Plagued with chronic understaffing and constant turnover, DHS failed to publish Neumann’s strategy report until January 2020. Four months later, she quit, unable to reconcile her own beliefs with Trump’s actions and rhetoric, which she says was emboldening white supremacists. (She has since appeared in a video produced by Republican Voters Against Trump, saying she is voting for Joe Biden this year because the country cannot afford four more years of Trump.)

A DHS spokesperson said the idea that the Trump Administration has made it more difficult to prevent human trafficking is “ludicrous” and pointed to its new center on trafficking. But the spokesperson did not answer specific questions about the strategy report or concerns raised by Neumann and anti-trafficking advocates. “The Trump administration has made the historic fight to end human trafficking a top priority,” the spokesperson said.

The State Department’s annual Trafficking In Persons reports from recent years, which evaluate the human trafficking landscape and efforts to combat the crime in countries around the world, corroborate some of Neumann’s concerns.

Human trafficking prosecutions and charges fell in 2018 and 2019, and T visa approvals have fallen all three years so far under Trump, according to the most recent Trafficking in Persons reports. The reports are also full of notes about areas that advocates see as needing improvement, from immigration deterrents to victims being arrested for committing sex acts or other crimes their traffickers compelled them to do. In July, Mark Taylor, a former State Department official who coordinated the reports from 2003 to 2013, wrote an op-ed in the Bangkok Post condemning the Trump Administration’s actions and arguing that by continuing to rank itself a Tier 1 nation, the highest designation for counter-trafficking, the U.S. was undermining its own credibility. (The State Department declined to comment for this article.)

Neumann says she and many of her colleagues understood the dilemma they were in: the work of countering human-trafficking was being subjugated to a broader agenda, perpetuated by President Trump and Stephen Miller, a long-serving top advisor who has pushed the Administration’s most extremist immigration policies. “We would go to these meetings with [the Department of Justice] and State and sometimes the White House, and everybody would be looking at this problem going like, ‘We’ve got to get these T visa numbers up,’” Neumann says. “You’re kind of looking around the room going, ‘Hey, everybody understands that in this Administration this problem will never be solved because Stephen Miller won’t let it be solved.”

’What’s going to happen to me?’

Emma, who is just learning how to navigate her adopted country, isn’t privy to most of the details of these Ivory Tower policy discussions. But the implications of Trump’s policies in her daily life are crystal clear: because of delays seemingly designed to deter new T visa applications and reduce the total number offered each year, she finds herself in a prolonged legal purgatory. Until a decision is issued on her case, she has no legal status, no access to benefits, like Medicaid, and no work authorization. She’s also been given no indication of when the government will give her an answer. If she is eventually granted a T visa, she could be allowed to stay in the U.S. for up to four years, and could be eligible to apply for permanent status. If her application is denied, she could begin deportation proceedings.

The indecision puts her in an impossible position. After the raid last summer in Kentucky, Emma found a job as a live-in housekeeper in Maryland with a family that did not ask about her legal status. But when COVID-19 hit in March, Emma panicked. “What if I contract the disease, what is going to happen to me? What about health care?” she thought. “What if I die alone?” She had a conversation with the man she’d been dating and the two of them decided she’d move in with him so they could be together, and she would not have to keep working and expose herself to COVID-19. She is much happier now, she says.

After years of harassment and trauma, Emma would like to stay in the U.S. permanently. She dreams of maybe opening her own beauty store one day if she can get legal status. But in the meantime, she is hoping that her own personal nightmare will help law enforcement officials. She wants them to find and punish the network that exploited her so that “they do not continue to lie to the innocent people,” she says. “They shouldn’t let innocent people be cheated and forced to do things that they don’t want to.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com