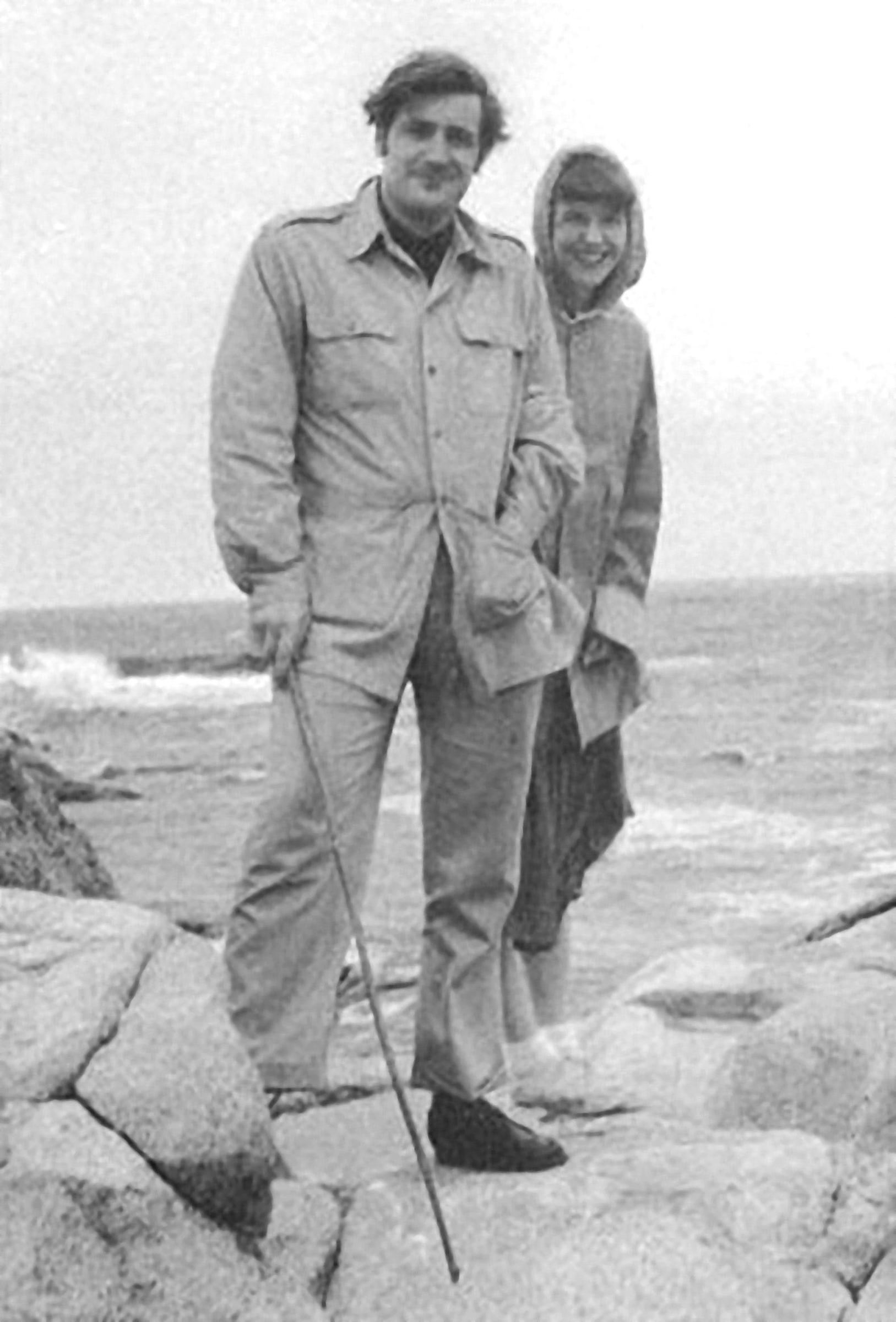

Sylvia Plath was one of the greatest American writers of the twentieth century. In 1956, while on a Fulbright Fellowship at Cambridge University, she married the British poet Ted Hughes after a whirlwind courtship. They were both ambitious, and hoped to become the leading poets of their generation. But what began as a Shakespearean “marriage of true minds” ended in tragedy. Hughes left Plath for another woman in 1962; suffering from depression, Plath took her own life in 1963.

This excerpt picks up in happier times. In 1957, Plath and Hughes left England for Massachusetts, where they planned to spend the summer writing on Cape Cod before Plath took up a teaching position at Smith College. Plath had not published a story in five years, and she hoped to use this uninterrupted time to write new fiction that would impress editors at women’s magazines like Mademoiselle and Ladies’ Home Journal. Her efforts were unsuccessful, but the summer itself marked an important creative point in Plath’s life. Although her time on Cape Cod was marked by professional setbacks, self-doubt, and marital tension, she managed to find the inspiration for one of her finest poems, “Mussel Hunter at Rock Harbor,” and sketch the outline of her best-selling novel, The Bell Jar.

On July 13, 1957, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes arrived in Cape Cod for their second honeymoon. They had been married for over a year, but their London wedding had been a secret. Now, newly arrived in Massachusetts, they celebrated their marriage with Sylvia’s family and friends in Wellesley before heading to Eastham, where Sylvia’s mother Aurelia had rented them a shingled cottage amid the pines at the Hidden Acres Cottage Colony for six weeks. Nauset Light Beach was three miles to the east, Cape Cod Bay three miles to the west. They had no phone and no car, just their bicycles, Sylvia’s new Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter, some books, and clothes. Ted found the two-bedroom cottage comfortable and modern. He especially liked the screened-in porch. “When you step from the doorway pine needles touch your head, and as you sit there you see chipmunks & little red squirrels among the house-high trees,” he wrote his sister Olwyn.

For the first few days, they luxuriated in silence and ate simple meals Sylvia prepared in their single frying pan. She was delighted to see four of her poems in that July’s Poetry. Yet soon a neighbor began playing his radio too loudly, and the biting horseflies became a nuisance. “God has to remind us this isn’t heaven,” Sylvia wrote in her journal. The cottage itself proved rather too rustic—Sylvia sent Aurelia a long list of “suburban” supplies they needed (eggbeaters, pillowcases, facecloths, nail clippers, coffee mugs), while the lack of a car proved a major inconvenience. They had to rely on the colony’s caretaker, Mrs. Spaulding, for frequent rides into town. Mrs. Spaulding, in turn, felt free to drop by for coffee and conversation—just the kind of suburban mingling they had longed to escape. And even in paradise, Sylvia had disturbing dreams, all “diabolically real.” “Why these dreams?” she wrote in her journal. “These last exorcisings of the horrors and fears beginning when my father died and the bottom fell out. I am just now restored. I have been restored for over a year, and still the dreams aren’t quite sure of it. They aren’t for I’m not. And I suppose never will be.”

Everything would be better, Plath reassured herself, once she began “the painful process of getting writing again after nine months.” Her first day back at the typewriter produced only one “good image”: “This bad beginning depressed me inordinately.” As she and Hughes walked to the beach along busy Route 6, the cars seemed to her “deathly . . . like killer instruments from the mechanical tempo of another planet.” The “badly begun poem” weighed on her all day. She vowed to “never get in this rusty state again, for writing is the prime condition of both our lives & our happiness: if that goes well, the sky can fall in.” But this American honeymoon yielded little in the way of new writing. She had not published a story in a women’s magazine in five years, and she spent much of her time in Eastham trying to write fiction that would sell. She wanted to show the editors at the “slicks” that the twenty-year-old adolescent writer had transformed into a more mature literary voice. But she feared that creative paralysis would bring on another depression.

While Hughes began writing the poems that would go into his second collection, Lupercal, Plath worked on four stories. None would be published, but it was during this time that she outlined the plot and themes—in “The Trouble-Making Mother”—that would become the basis for The Bell Jar:

Get tension of scenes with mother during Ira and Gordon crisis. Rebellion. Car keys. Psychiatrist. Details: Dr. Beuscher: baby. Girl comes back to self, can be good daughter. Sees vision of mothers [sic] hard-ship. Yes yes. This is a good one. . . . Mental hospital background. Danger. Dynamite under high tension. Mothers [sic] character. At first menacing, later pathetic, moving. Seen from outside first, then inside. Girl comes back: grown bigger, ready to be bigger. Like mother, yet furious about it. Wants to be different. Bleaches hair. Policemen. Annoying her. Story in newspapers. After suicide attempt. Earthy Dr. Beuscher. . . . MOTHER-DAUGHTER. Troubles. Graphic. A real story.

The girl’s name would be Judith Greenwood—like Esther Greenwood, the future heroine of The Bell Jar—and she would be “a statement of the generation. Which is you.” After starting this story during the third week of July, Plath felt the “old fluency” return “at last, at last.” The story, as her confident, fast-moving outline suggests, was writing itself. In her journal she wrote, “I must say, I’m surprised at the story: it’s more gripping, I think, than anything I’ve ever done.” She finished on July 25 and sent the piece off to The Saturday Evening Post, where it was quickly rejected. Yet the writing restored her faith: “And now, aching, but surer and surer, I feel the wells of experience and thought spurting up, welling quietly, with little clear sounds of juiciness. How the phrases come to me.” Plath thought it her “first good story for five years” and later realized that it contained the seeds of a novel.

Each afternoon, after four hours of writing, Sylvia and Ted biked to the shore. There, they swam along a sandbar halfway between Nauset Light Beach and Coast Guard Beach, with “clear level water & long rollers.” The sand and the blue horizon stretched in both directions for miles; Sylvia had fantasized about such summer afternoons during the long Cambridge winters. In the evening, they read. Plath immersed herself in Virginia Woolf’s diary, The Waves, and Jacob’s Room. She reread and underlined the end of The Waves, which chilled her as much as the end of James Joyce’s “The Dead.” “Virginia Woolf helps,” she wrote in her journal. “Her novels make mine possible.” Woolf’s writing inspired her to believe in her own vocation and even to “go better than she.” She promised herself: “No children until I have done it. . . . My life, I feel, will not be lived until there are books and stories which relive it perpetually in time.”

When it rained, Sylvia cooked and baked cakes. She knew she tended to “escape into cooking,” as Hughes put it, when “faced by some tedious or unpleasant piece of work.” Now she mined her baking habit for dramatic potential in “The Day of the Twenty-Four Cakes,” which she outlined in her journal:

woman at end of rope . . . quarrel with husband: loose ends, bills, problems, dead end. Wavering between running away or committing suicide: stayed by need to create an order: slowly, methodically begins to bake cakes, one each hour. . . . Husband comes home: new understanding. She can go on making order in her limited way: beautiful cakes: can’t bear to leave them.

Plath was aware of her story’s parodic elements, and she wondered whether she should use a “Kafka lit-mag serious” tone, or a style more appropriate for The Saturday Evening Post. In the end she decided to experiment with both. The story has not survived, but its outlines point to Plath’s unsettled approach to domesticity. In her stories about housewifery and motherhood— “The Visitor,” “Sunday at the Mintons,” “Home Is Where the Heart Is,” “The Wishing Box,” “Sweetie Pie and the Gutter Men,” and “Day of Success”—wives respond to their subordination with murderous fantasies, suicidal unhappiness, or smug superiority over “career women.” They are painful referendums on dreams deferred.

These tensions came to a head in “Dialogue Over a Ouija Board,” the first poem Plath had written in six months. She found the form liberating: “strict 7 line stanzas rhyming ababcbc,” which she challenged herself to make sound “like conversation.” The poem had a biting undercurrent. Just as she had written about unhappy, ghostly doubles during her first honeymoon in Spain (“The Other Two”), she now wrote about another glowering married couple. Although Plath frequently gave the impression to others that she shared Hughes’s interest in the occult, “Dialogue Over a Ouija Board” reminds us that she was more ambivalent. In the poem, the wife, Sybil, is skeptical of her husband Leroy’s ability to interpret “messages” from the spirit they nickname Pan. “Pan’s a mere puppet / Of our two intuitions,” Plath writes, a “psychic bastard / Sprung to being on our wedding night.” The couple fights about Pan’s meaning.

The poem speaks to creative tension within the marriage. To others, and herself, Sylvia always described Ted as her ideal. In her journal that July she wrote, “he sets the sea of my life steady, flooding it with the deep rich color of his mind and his love and constant amaze at his perfect being: as if I had conjured, at last, a god from the slack tides.” But her work suggests a more complex professional relationship. As Sybil says, “I glimpse no light at all as long / As we two glower from our separate camps, / This board our battlefield.” By creating fictional doubles of herself and Hughes, Plath simultaneously addressed and contained her anxieties about the creative partnership. She refused the role of muse; like the heroine of her unfinished novel Falcon Yard, she felt herself a “voyager, no Penelope.”

As July turned to August, the couple became listless in Eastham. The temperature was in the high nineties, “terribly still and sultry”—and Sylvia longed for the “nip” of fall weather. The laundry came back dirty; she could not make sense of Faulkner. In late July, a pregnancy scare brought on “a black lethal two weeks” as bad as the weeks that had preceded her 1953 suicide attempt. She was paralyzed with fear; if she were pregnant, there would be no Smith job, no traveling, no novel: “clang, clang, one door after another banged shut with the overhanging terror which, I know now, would end me, probably Ted, and our writing.” She felt she would resent her child for closing the doors she had pried open. The couple biked through a driving thunderstorm to a doctor in Orleans on August 4 for a blood test. The next day her period came. But she had lost her momentum.

Ted, too, became restless. He was “paralysed” by the cost of the cottage Aurelia had rented for them—“Dowry almost” at $70 a week. He developed an ear abscess, which caused pain, fever, and severe facial swelling. “Conditions haven’t been as ideal as they’ve seemed,” he wrote Olwyn that August. Sylvia endured another setback in early August when she learned that her manuscript had not won the Yale Younger Poets contest. (John Hollander had won.) For over two months she had fantasized about her own moment in the sun—the introduction by Auden, the ensuing New Yorker acceptances. She confided in her journal:

Worst: it gets me feeling so sorry for myself, that I get concerned about Ted: Ted’s success, which I must cope with this fall with my job . . . feeling so wishfully that I could make both of us feel better by having it with him. I’d rather have it this way, if either of us was successful: that’s why I could marry him, knowing he was a better poet than I and that I would never have to restrain my little gift, but could push it and work it to the utmost, and still feel him ahead.

Now she would have to begin again. She reread her manuscript with a newly critical eye, hating the poems for what she now saw as “bland lady-like archness or slightness.” She could hardly believe Adrienne Rich and Donald Hall, with their “dull” poems, were ahead of her. She had not worked hard enough, she wrote in her journal, “Not one tenth hard enough.” She must become “stoic” again, and “fight.” There would be no more stories with “phony plots,” “the old lyric sentimental stuff.”

By late August, Sylvia had begun counting down the days until they could leave the Cape. She felt lazy and unproductive, and hardly realized that she had experienced two creative breakthroughs. In July, she had sketched a rough outline of a major plotline of The Bell Jar, and, in late August, she had pondered a coastal scene in her journal that would inspire her fine poem “Mussel Hunter at Rock Harbor,” which The New Yorker would accept in June 1958: “the weird spectacle of fiddler crabs in the mud-pools off Rock Harbor creek. . . . An image: weird, of another world, with its own queer habits, of mud, lumped, under-peopled with quiet crabs.” Hughes would later write of their coastal explorations in his Birthday Letters poem “Flounders.” “Was that a happy day?” he wondered, remembering how he and Plath had been swept out to sea in their dinghy by a strong current. They eventually rowed to a sandbar, where “big, good America found us”; a powerboat towed them back to the dock. Back in the shallows, they caught flounders “big as plates.” For Hughes, the day symbolized the life of adventure, beauty, and bounty they might have led had they not sacrificed their marriage to art: “we / Only did what poetry told us to do.”

Excerpted from RED COMET: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark. To be published October 27, 2020 by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2020 by Heather Clark.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com