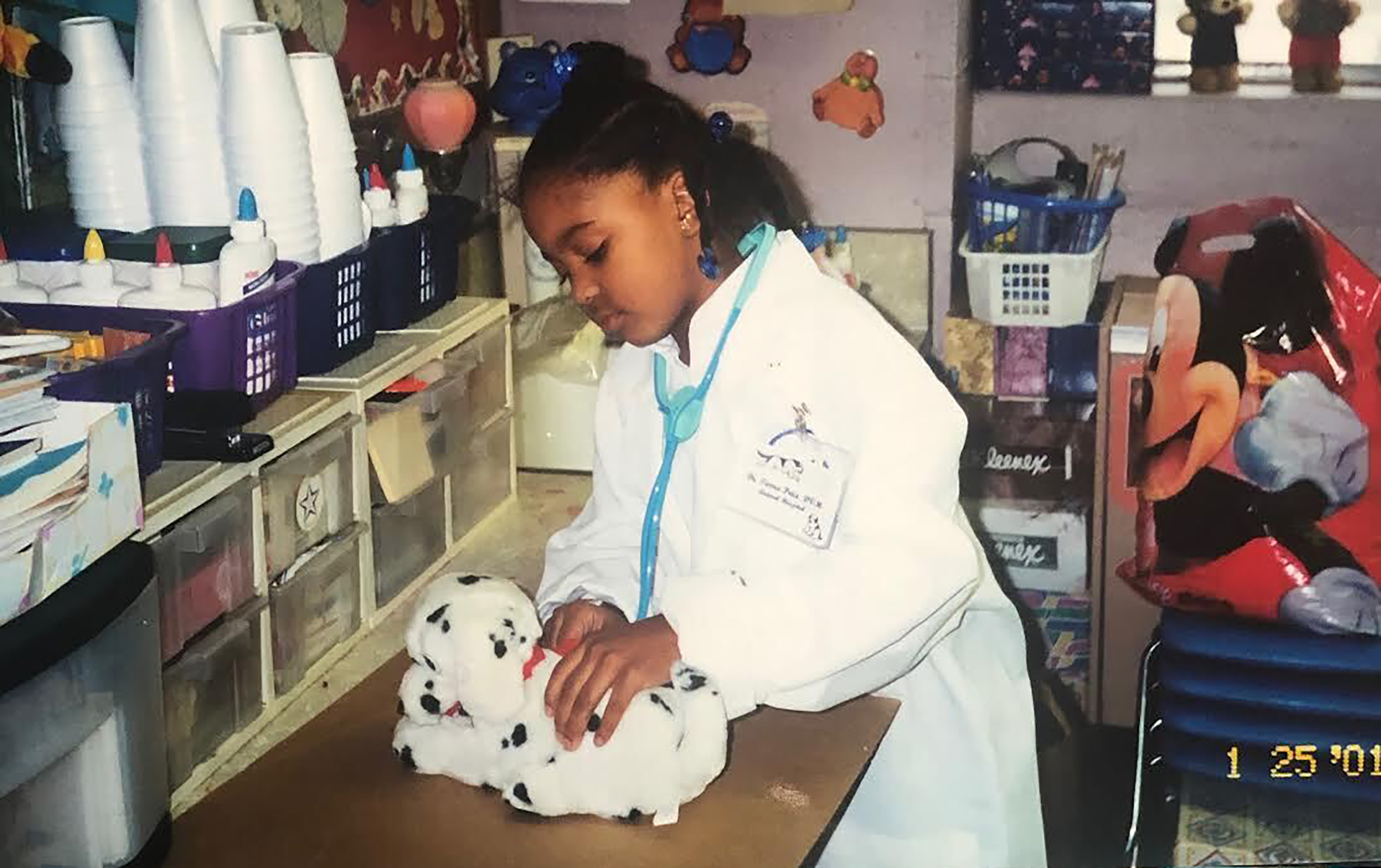

As a child, Tierra Price was mesmerized by Dr. Dolittle, portrayed by Eddie Murphy in the 1998 film—not only because he could talk to dogs and sad circus tigers, but because he was a person of color who treated animals. “That resonated deeply with me,” says Price, who wore an oversized white coat and carried around a stuffed Dalmatian for her first-grade career day. “I grew up thinking that I was going to be one of the first Black veterinarians because I had never seen any,” says Price, now 26.

There were no Black doctors at vet clinics near her Louisville, Ky. home or at the local animal shelter where she volunteered. Price didn’t see her first real Black veterinarian until she was 19 and participating in a veterinary program for minority undergraduates. By the time she started veterinary school, she felt like an outcast. In 2018, Price created an online networking group for Black vets just to connect and commiserate with people who looked like her. “I was going into a profession I didn’t really belong in,” she says.

Years later, not much has changed. Veterinarians are projected to be among the most in-demand workers in the next decade. As more people of all races own pets, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) predicts jobs for vets and vet technicians will grow 16% by 2029. Nearly 65% of white households have pets, 61% of Hispanic households have pets, and almost 37% of Black households have pets, according to the most recent industry data. Yet pet lovers are faced with a predominantly white world once it’s time to see a vet. Of the more than 104,000 veterinarians in the nation, nearly 90% are white, less than 2% are Hispanic and almost none are Black, according to 2019 BLS figures.

In this day and time, you don't stay that way unless you're ignorant to the fact that diversity is good.

This spring, Kimberley Glover spent nearly two months searching for a Black veterinarian in Birmingham, Ala., to care for her 2-year-old puppy Stokely—named after civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael—and to serve as a role model for her two children, who attend predominantly white schools. After scouring the internet and Facebook groups for Black pet owners, she finally received a suggestion from a college classmate, but the clinic was too far away.

“I have given up the search, honestly,” says Glover, 46. “It just tells me there’s more work to do.” Price, who graduated from the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine in May and is now a veterinarian in Los Angeles, agrees. “We have so much catching up to do,” she says.

Stark disparities have permeated the vet world for decades, advocates say, long before George Floyd’s death in May sparked a national movement for racial justice. In 2013, the profession was dubbed the whitest in America. “It has always been a problem,” says Annie J. Daniel, who founded the nonprofit National Association for Black Veterinarians (NABV). “This was just the wake-up call.”

Despite youth outreach efforts at schools and community partnerships to grow the number of Black veterinarians, the group has barely moved the needle since it was formed in 2016. In fact, the number of Black vets dropped from 2.1% of the total vet population in 2016 to below 1% in 2019, which Daniel says is largely due to systemic racism. “In this day and time, you don’t stay that way unless you’re ignorant to the fact that diversity is good,” Daniel says. “Or,” she adds, “you just don’t care that you’re purposefully omitting a group of people.”

Many issues prevent the veterinary profession from becoming more diverse. Chief among them is a lack of access and exposure to veterinarians at an early age, particularly among children who live in urban or low-income areas, where pet healthcare is considered more of a luxury, advocates say. “It’s not that they don’t want to become veterinarians,” Price says, “but they don’t know that it’s a career option.”

Such was the case for Dr. Will Draper, 53, who didn’t live near vet clinics or animal shelters while growing up in a predominantly Black community in Inglewood, Calif. Differing cultural views on animals also limited his exposure to veterinarians. “I didn’t really have many pets growing up because my father didn’t like animals,” says Draper, who now runs his own practice in Decatur, Georgia with his wife. Draper loved animals, but he didn’t realize he wanted to enter the field until his father took him to see the College of Veterinary Medicine at his alma mater, Tuskegee University. The historically Black college has educated more than 70% of the nation’s current Black vets. Draper was hooked after one visit.

‘Mountains and mountains of debt’

For many others, getting into vet school and paying for it pose additional challenges. On top of requiring prospective students to complete a number of undergraduate prerequisite courses, which can be costly, many top vet schools require or recommend that applicants have hundreds of hours of clinical experience working with animals and licensed veterinarians. Even before the pandemic, Price says that was tough for applicants who don’t live near clinics or shelters, especially if they have to work to support themselves or their families. “A lot of the experience that you have to have to get into veterinary school, you’re not paid for,” Price says. “That really selects for populations that have the luxury of forgoing income.”

In 2019, veterinary students in the U.S. graduated with an average of $150,000 in debt, according to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). Yet federal data shows the median annual wage for veterinarians in 2019 was about $95,000. Starting salaries were much lower. It costs graduate students attending in-state vet schools at Cornell University in New York and at the University of California, Davis upwards of $32,000 per academic year for just tuition and fees, according to the schools’ websites. Tuition for Tuskegee’s vet school costs more than $20,000 per semester. “When they come out of veterinary school,” Price says, “they’re under mountains and mountains of debt.”

While many young veterinarians are wracked with student debt, no matter their race, daily discrimination in the workplace is another job challenge. Draper—who stars in a reality TV show called Love & Vets on Disney Plus—is often the first Black veterinarian his clients have ever seen. In turn, at least two have refused his service. More than 30 years ago, Draper says an older white man balked when he saw that Draper was Black. The man insisted a white doctor treat his chihuahua, Tiny, who was suffering from congestive heart failure.

“He said Tiny doesn’t see colored people,” Draper recalls. He saved the chihuahua that day, but the man referred to Draper as “the colored doctor” for the next couple of appointments. “Nobody would have blamed me if I told that guy to screw off,” Draper says. “But that’s not what it was about.” When asked if clients have mistaken Draper for a technician or assistant, Draper laughs. “All the time,” he says, adding that they often insist on speaking to the clinic’s owner. “One time, I even said, ‘Hold on,’” Draper says. “I walked away and came back and said, ‘I am the owner.’”

For Black veterinarians and pet owners, systemic racism in the industry is the norm. That’s why Cheryl Kearney, 65, has no problem driving more than 50 miles to and from Detroit each time her 6-month-old kitten, Roger, needs to see a doctor. Kearney says she’s had negative experiences with her own white doctors speaking to her condescendingly, assuming that because she’s a Black woman, she wouldn’t understand their explanations unless they dumbed them down. Kearney says she couldn’t bear enduring that discomfort when it came to caring for her “baby” Roger, so she made it a point to find a Black vet. “It was a much more personal experience,” she says.

Dion Hobbs, a 46-year-old Houston financial advisor, also noticed that difference when he switched to a Black vet. Hobbs had been taking his 11-year-old dog Sadie to the same vet, who’s white, for more than a decade when Sadie cut open her back leg in June—her first major injury. Hobbs says he was disappointed with the clinic’s bedside manner during a vulnerable and frightening time.

“Competency wasn’t the issue,” he says. “I thought there would at least be a little bit more warmth in the conversion.” Hobbs says he doesn’t think race played a major role in what he considered Sadie’s chilly treatment, but he saw the experience as an opportunity to give his business instead to a Black veterinarian, who he says has shown more compassion. “If I’m going to spend my dollars,” he says, “why not have it go to someone who looks like me?”

An industry slow to change

When an industry is stifled by homogeneity, it can breed a culture of leaders often inflexible to change, advocates say. Amid a pandemic, when social distancing restrictions limited in-person appointments, some veterinarians criticized the AVMA for not tweaking its telemedicine policy, which discourages vets from prescribing medication or diagnosing new pet patients remotely except in emergency situations. The AVMA said it does not regulate or set laws that govern the use of telemedicine, but some vets say industry leaders should be better champions for changing those laws nationwide. For some, it was the latest example that the industry was not keeping up with the times.

“The veterinary industry, in general, has been very resistant to change in every facet,” Price says. Since July, nearly 6,000 people have signed an online petition, written by nearly a dozen multicultural advocacy groups, calling for the AVMA to take concrete steps to assess where it stands with inclusion issues and to ensure an equitable process for all. “Our profession could really benefit from more diversity because it brings creativity,” Price says. “It brings innovation and it brings new ideas.”

Pets need us. People need us, and aspiring veterinarians need us to drive a change for the profession.

In a statement to TIME, the AVMA, which has more than 95,000 members, said it was “building on” efforts to “further infuse” inclusion into its programs and outreach. It added that it would develop new programs to bring leaders of color to the forefront and that it would work to amplify multicultural vet advocacy groups. In July, the AVMA approved the idea of forming a commission to assess diversity issues, but it has not yet been created. “Transformative change doesn’t happen overnight,” says AVMA President Dr. Douglas Kratt. “It will take an industry-wide, profession-wide collaborative effort to move the needle and to attract more young people to consider a career in veterinary medicine. No single organization can do this alone.”

Now, amid America’s racial reckoning, more leaders are pledging to step up. On Sept. 14, Banfield Pet Hospital, one of the nation’s largest employers of veterinary professionals, announced it would invest $1 million in diversity efforts and ensure at least 30% of its veterinarians and support staff are people of color by 2030. “This is absolutely just the start,” says Dr. Molly McAllister, Banfield’s chief medical officer. Banfield also gave $125,000 to help in-need Tuskegee vet students afford their schooling. “This is a critical time,” McAllister says. “Pets need us. People need us, and aspiring veterinarians need us to drive a change for the profession.”

A new vet school that opened at the University of Arizona in August is among those that have stopped requiring applicants to have a minimum number of hours of clinical experience. Instead, applicants can explain how they’ve found success in the face of hardship or how they’ve adapted to change. Of the 110 students in its inaugural class, 33% were minorities, officials say.

“We should not exclude someone from our profession just because they may come from an underserved community,” says Julie Funk, the vet school’s dean. “The very future of the veterinary profession is dependent on our ability to serve society as a whole.” Several other vet schools have recently hired managers to oversee diversity efforts or have donated to scholarships that help underrepresented minority students. The Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges says it reached a milestone in 2020 of having about 20% of its total enrollment consisting of racial and ethnic underrepresented minorities.

There’s no better moment for industry leaders to commit, advocates say. The demographics of the U.S. are changing, and so are those of pet owners. A record high number of Americans own pets, according to the American Pet Products Association trade group, with estimates ranging from 56.8% to more than 65% of U.S. households. Minority groups are fueling that growth, a 2019 study found. Between 2008 and 2018, the number of Hispanic pet owners increased 44%, the number of Black pet owners grew 24% but the white pet owner population went up only 2%, according to the study. At this rate, Daniel says, the industry could suffer financially if it doesn’t keep up with the needs of the changing pet-owning population.

“We have to do more,” Daniel says, “and this is the time.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com