In 1979, Howardena Pindell quit her job in the curatorial department of The Museum of Modern Art to start teaching at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Months into her new profession, she was a passenger in a car accident that left her with a hip injury and a dent in her head, causing memory loss. The near-death situation inspired an epiphany for Pindell, already an artist outside of her working hours: she needed to voice her opinion, she needed to do it now, and her art was the perfect way to do it.

The accident propelled Pindell, then in her mid-30s, into a career making work that overtly touches on subjects others often feared were too political for the art gallery, in groundbreaking pieces like Free, White and 21 and Separate But Equal Genocide: AIDS. Now, Pindell will have a solo exhibition of her work as The Shed, a cultural center in New York City’s Hudson Yards, reopens its doors after seven months. Pindell has had her work regularly exhibited since the ‘70s, and this new exhibition, Rope/Fire/Water, comes just two years after her first major museum retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Curated by Adeze Wilford, Rope/Fire/Water will be on view from Oct. 16 through April of next year, with its centerpieces focused on the violent, barbarous nature of racism, while additional works juxtapose those themes with an eye toward healing.

At the heart of the show is a new film of the same name, which is the artist’s first video work in 25 years. As Pindell, now 77, explains in her own voice in the film, the work was inspired by a traumatic childhood memory: she was at the home of a friend, whose mother was cooking meat for dinner, when she opened an issue of LIFE magazine to find a graphic image of a lynched Black man. Pindell could not eat meat for a year.

She first pitched the idea for Rope/Fire/Water in the early 1970s as a performance piece to a group of female artists, all of whom were white, at A.I.R. Gallery, where Pindell was a founding member. A.I.R., which stands for Artists in Residence, is the first non-profit, artist-run gallery for women in the U.S. Pindell’s idea was turned down—an example, as she explains it, of the unwillingness of white feminists at the time to engage with issues of race. Now, as part of The Shed’s mission to help artists bring to life works that they have not yet been able to realize, Pindell was able to turn that painful memory into an informative, shocking and cathartic experience for viewers.

The complex mix of “the accident, the sense of being isolated by living in lofts for years, and the sense of not really being welcomed in the art world,” says Pindell, have all influenced her approach and the resulting works. And though she has been making work for over half a century, with the new opening at The Shed and the current racial climate, she’s felt that there are more eyes on her work now than ever before. “The killing of George Floyd moved many people who were not on the street in the 1960s with the civil rights movement, so we have a multicultural uprising against police violence and racism in general,” says Pindell. “Then, the light was shone on artists and myself in particular.”

“I put myself—the Black body—in the work”

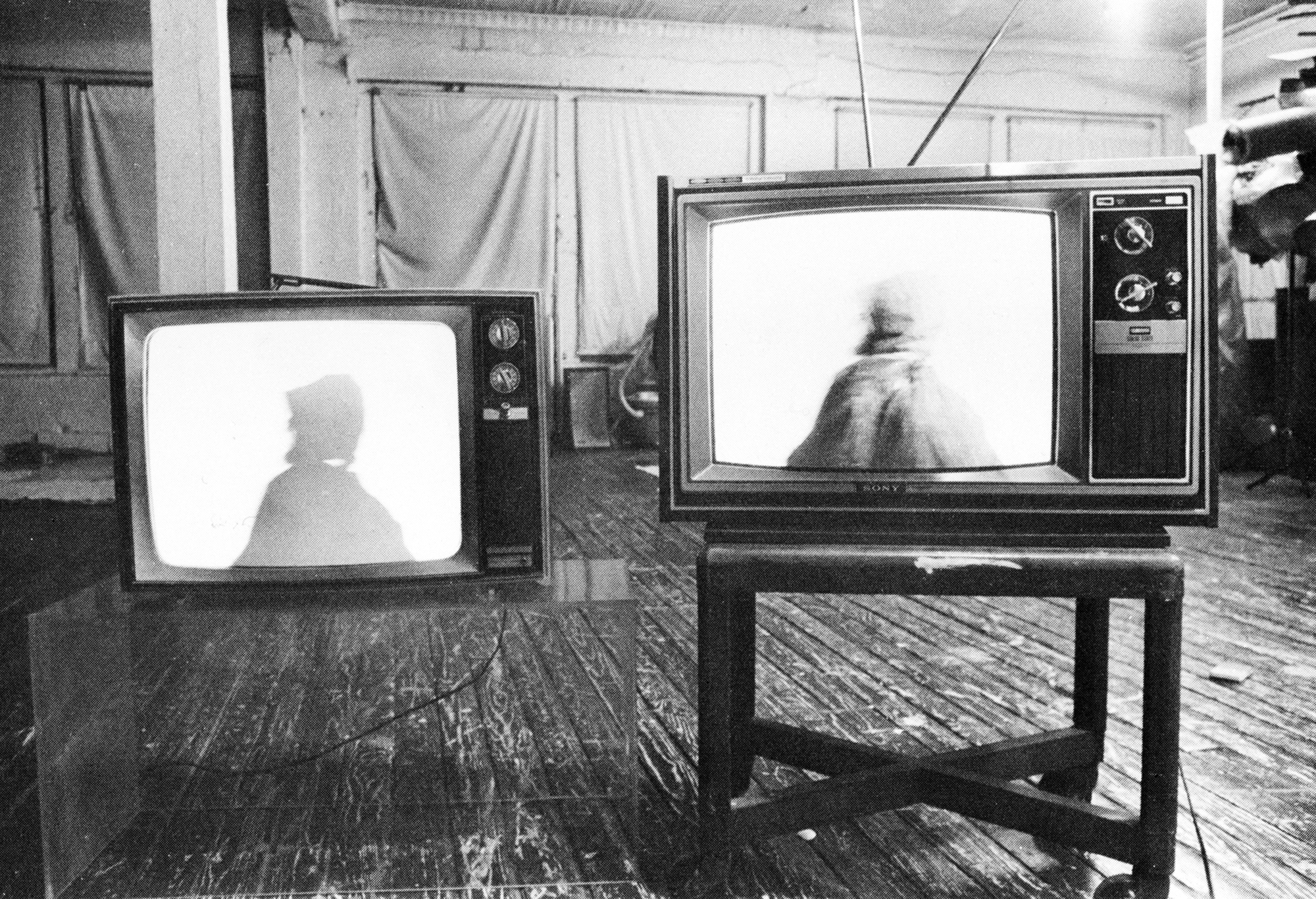

Pindell was trained as a painter and started to solidify her career in art working with experimental methods and materials. In the 1970s, she created “video drawings,” in which she would place clear sheets of acetate over her television, mark them up with numbers and arrows as the movements on the screen interested her, then photograph them. The scenes she would draw over were often of sports events—swimming, hockey, baseball. After the accident, she would continue this practice, but the drawings became political. She made one of George H.W. Bush with the text “LIAR” placed over his image in 1988, and in 2007 made one about news coverage of Hurricane Katrina.

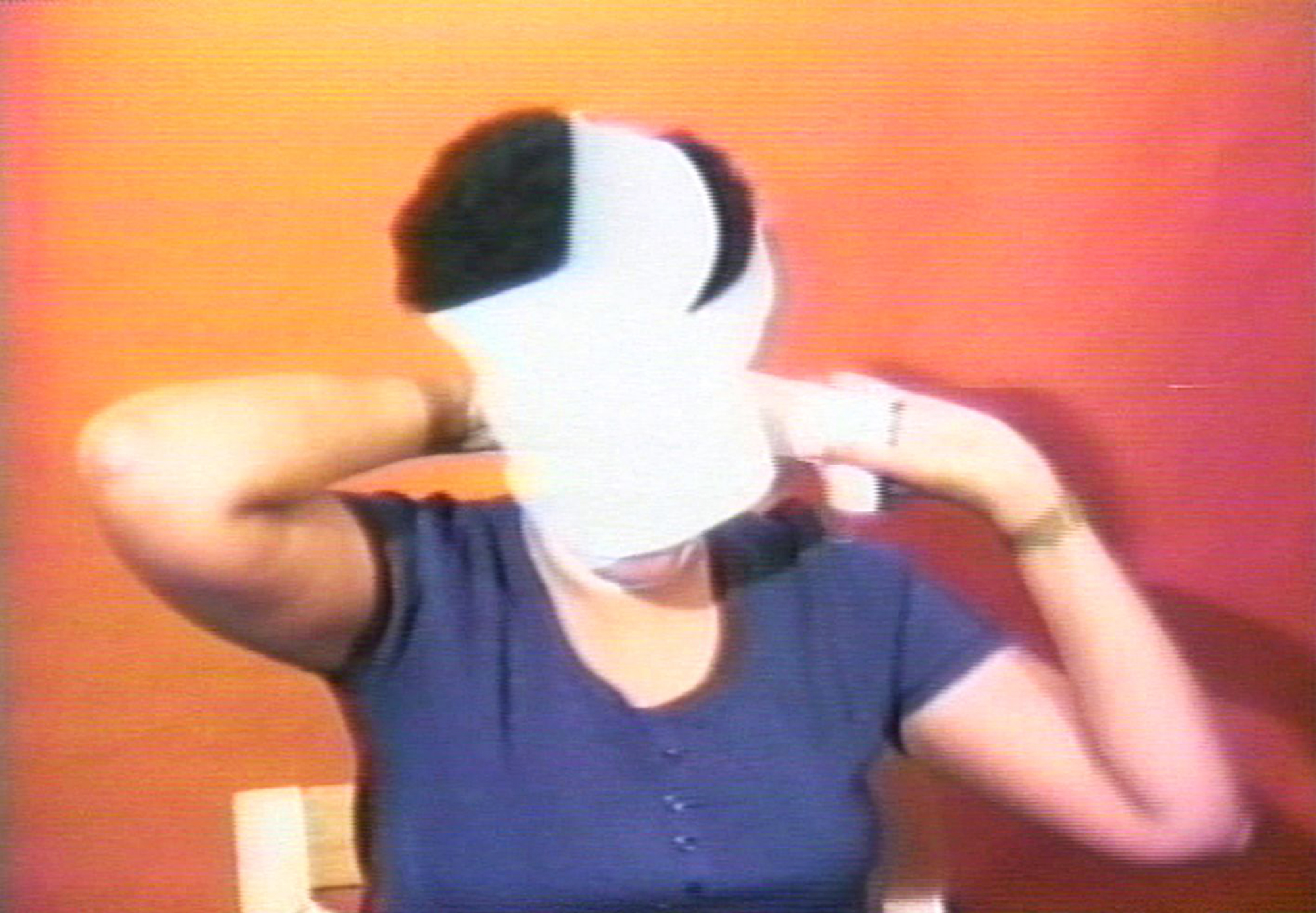

Pindell’s first seminal work arrived eight months after the accident. “When you have something like that, you get the fear that you might die and you have not expressed your opinion or tried to make anything better in the world, so that’s why my work became issue-related,” Pindell tells TIME. In 1980, she made Free, White and 21, a 12-minute, 15-second, plain-spoken video about her experiences facing racism and sexism. The film was shot in Pindell’s top-floor loft during what she called “one of the hottest summers in New York.” In the piece, she speaks directly to the camera, telling the viewer about a range of sexist and racist instances in her life, including when a high school teacher refused to place her in an accelerated course, saying that a white student with lower grades would do better. In addition to playing herself in the video, Pindell also acts as a white woman, who interjects throughout to call Pindell “ungrateful” and “paranoid.”

The performance video created waves in the art world when it was first shown at A.I.R. Gallery’s Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists of the United States exhibition. Pindell made it, in part, as a reaction to the white feminism she felt was prevalent in her industry and in everyday life. “A lot of well-known women artists, white women artists, whenever I brought up issues of race, they said they didn’t want to talk about them, that that was just politics,” says Pindell, describing her disenchantment with the art world. It was this kind of criticism that her reflections after the accident prompted her to incorporate more explicitly into her work.

“The white voice was the dominant voice. What the white male’s voice was to the white female’s voice, the white female’s voice was to the woman of color’s voice,” Pindell wrote about the making of the Free, White and 21. That dynamic—the white female’s voice suppressing the woman of color’s voice—is exactly what Free, White and 21 simultaneously exposes and dismantles. In the piece, Pindell uses her voice as an artist to overcome attempts at silencing her.

Though the piece garnered much attention, it received its share of criticism alongside the praise. When it was later exhibited in a solo show of Pindell’s, one of the exhibition’s catalog writers asked Pindell to take the video down. When she refused, the complaint was raised with the curator, who also shut it down. Pindell’s mission of using art as an autobiographical tool to expose racism was attacked by critics and students. “I got slack for it, I also got awards for it, but some people just didn’t want to deal with it, either because I put myself—the Black body—in the work, or they just felt that they wanted more mystery,” she explains.

Undeterred, Pindell continued working in a similar vein, further exploring how she could draw upon her own lived experiences to shed light on social injustice. Her 1988 work Autobiography: Water (Ancestors/Middle Passage/Family Ghosts) is made up of an outline of her body, engulfed in blue and surrounded by various body parts and the words “SEPARATE BUT EQUAL” in the lower right corner. She went on to have works in the permanent collections of museums around the world, including the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Copenhagen, New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C. In 1987, Pindell received a Guggenheim Fellowship in painting, and just last year, she was awarded the Archives of American Art Medal by the Smithsonian Institute.

“It’s taken a long time to break into the system”

This year, Pindell has created another video piece with the potential to agitate. And she says it’s a good thing that the piece is a film instead of a performance, as she originally pitched it to A.I.R., because “film has legs.” It can reach more people and, thus, create more impact. “I was disappointed that A.I.R turned it down, but now I feel it is a stronger statement,” she says. Though she is pleased with the piece finally coming to fruition, she says she feels desensitized toward the surge in attention toward her work. “I’ve been in New York 50 years, it’s taken a long time to break into the system … I just kind of am used to numbing myself and charging ahead,” Pindell explains.

The film, which is 19 minutes long, presents the viewer with blunt, macabre anecdotes and facts—ones viewers can’t argue with. The more than 4,000 men, women, and children lynched between 1877 and 1950. Details of the brutal murder of a pregnant Black woman. And so much more. Though her critics who argue that her works lack “mystery” could lodge the same complaints about the frankness of Rope/Fire/Water, that might just be the point. The data and stories of racial violence Pindell presents are gruesome on their own, needing little decoration to startle.

Pindell isn’t new to using data to get a point across; in the 1980s, the artist conducted a series of surveys of the art world, diving into the demographics of artists represented in museums and galleries. The results were presented in two papers, Statistics, Testimony, and Supporting Documentation and Commentary and Update of Gallery and Museum Statistics.

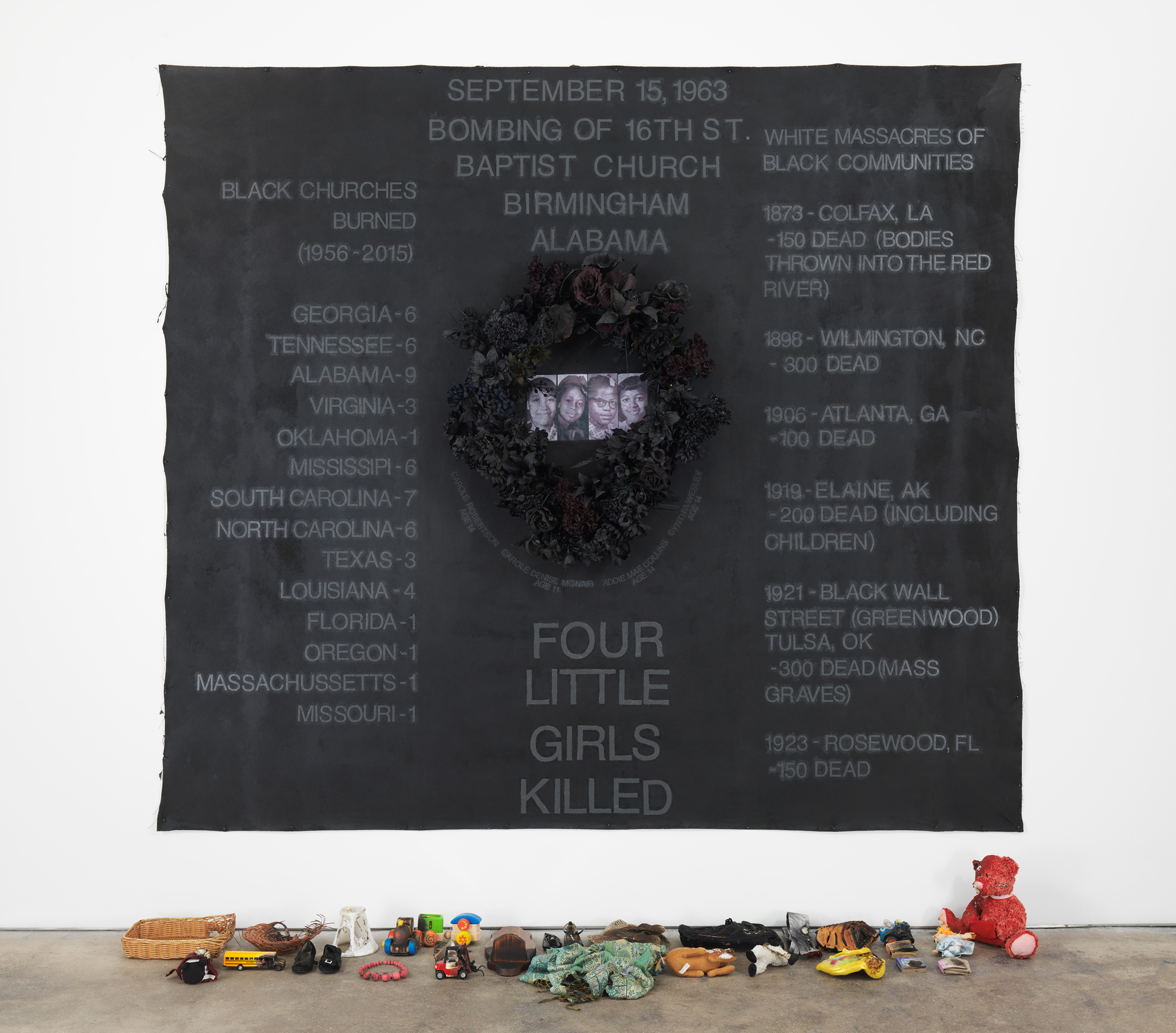

For the new opening, Pindell also created two black paintings spun off from the film, both ten feet wide and nine feet tall. Four Little Girls, a remembrance of Black churches that were burned between 1956 and 2015, and whose name is a reference to the victims of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963, is placed behind a shrine of burned objects, including a teddy bear and children’s books. The other painting, Columbus, is paired with black, silicone hands, bringing attention to Christopher Columbus’ practice of cutting off Indigenous people’s hands.

Other works in the exhibition include Pindell’s highly textured, glimmering paintings, such as Ko’s Snow Day and Songlines: Glacier. Pindell creates these works through a lengthy process of cutting canvases, sewing them back together, painting and drawing on paper, punching dots out of the paper and layering them onto her canvas. The result is a thick, multidimensional work of art that glows. Pindell’s aim is that these lightly colored, abstract works can be healing to viewers who have just witnessed the trauma presented plainly in her film.

Pindell, who lives and works in New York, can’t make it to see her work on display at The Shed in person, per her doctor’s request. But she’s well occupied anyway, hard at work on two other paintings, which are at the stage of being cut and sewn, and recovering from the intensity of creating the pieces for this latest show.

“As a Black American woman, I draw on my experience as I have lived it and not as others wish to perceive my living it as fictionalized in the media and so-called ‘history’ books,” Pindell wrote in an artist statement for a 1980 show at A.I.R. Gallery. Forty years later, it’s still an apt way to describe her work, and the way she literally deconstructs and reconstructs her canvases. She doesn’t merely take the canvas as it was given to her—she completely tears it down and builds it back up in her own way.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Anna Purna Kambhampaty at Anna.kambhampaty@time.com