Maria Fallon Romo has voted all her life. It’s important to her, and it was important to her when she cast her mail-in ballot for then-Democratic Senator Heidi Heitkamp in North Dakota’s 2018 midterm elections.

So Romo was stunned when, in the spring of 2020, the bipartisan Campaign Legal Center informed her that her vote had never been counted. Her ballot was rejected when election officials ruled that the signature on her ballot didn’t match the signature on her absentee ballot request form.

Romo, 54, has fought multiple sclerosis for over 20 years, a disease which, among other symptoms, numbs her hands and fingers and impacts her handwriting. “I didn’t know my vote didn’t count, and that was an important election to me,” Ramo says. “I should have been notified.”

Romo was a plaintiff in a suit brought in the spring by the Campaign Legal Center against North Dakota’s signature matching laws, which resulted in a federal judge ruling in June that the state must adopt a “notice and cure” process. Now, state election officials must notify voters if their mail-in ballots are deemed invalid and give them opportunity to correct—or “cure”—the problem in time for their vote to be counted. In his opinion, the judge ruled that “attempting to contact voters and allowing an opportunity to verify ballots” met “the bare-minimum requirements of procedural due process.”

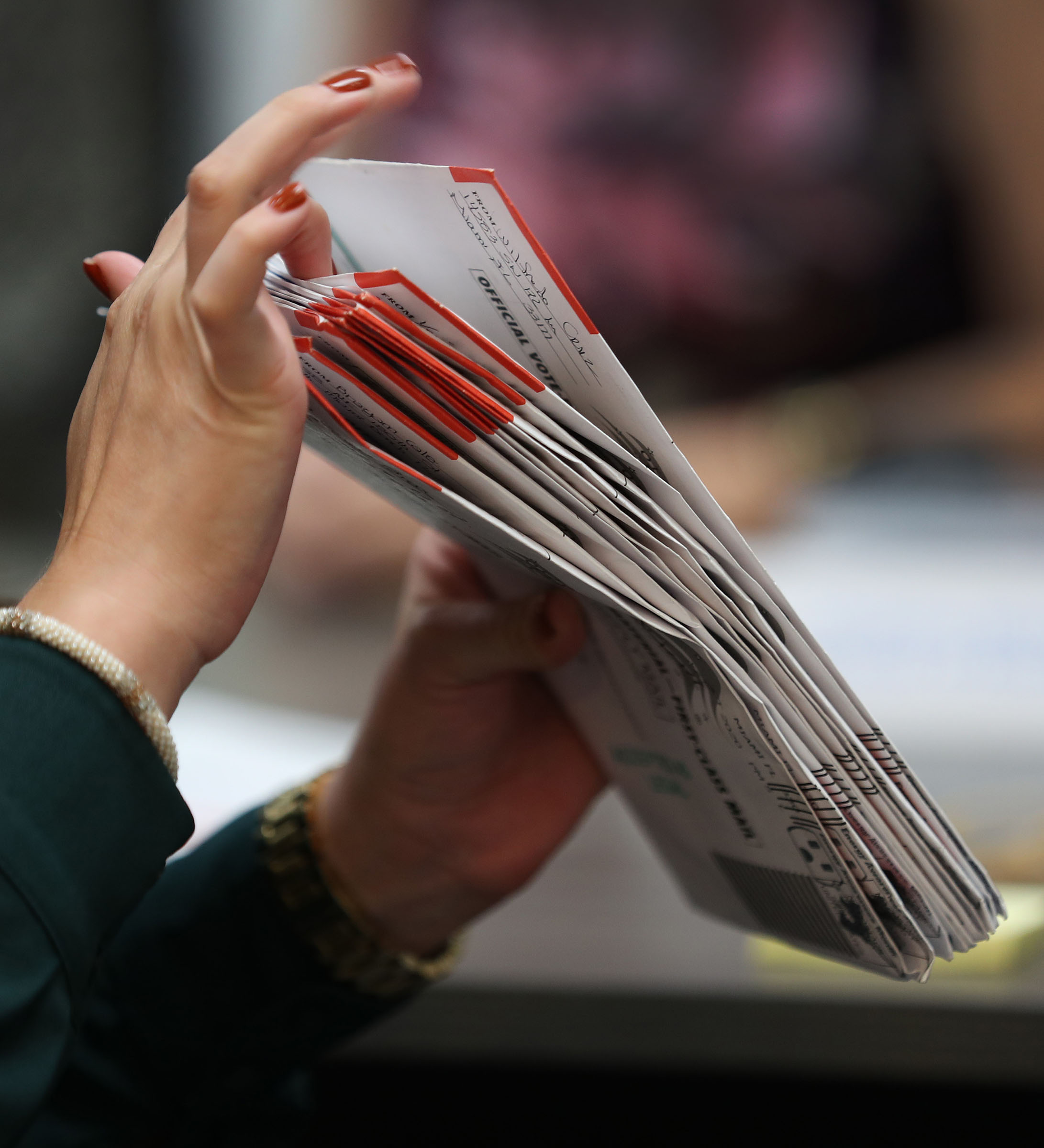

As an unprecedented number of voters turn to voting by mail amid the COVID-19 pandemic, more and more states are adopting “notice and cure” processes. Eighteen states already had some type of cure process before the pandemic, and at least 11 more will have a new system in place by Nov. 3, according to the advocacy organization The Voting Rights Lab (VRL). In the run-up to the polls, voting rights groups have filed over a dozen lawsuits across the U.S. pushing states to adopt these cure systems. Some legal battles are still ongoing, including in the key swing state of North Carolina, where a recent ruling from a federal judge provided some clarity on a cure process for more than more than 6,800 votes—many from voters of color—that have been in limbo.

Whether or not additional states adopt cure processes could determine if hundreds of thousands of ballots are counted this election. Roughly 318,700 mail-in ballots were rejected in the 2016 general election, according to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, and a recent NPR analysis found that more than 550,000 were rejected in this year’s presidential primaries. As millions of voters are expected to cast their ballots by mail for the first time, experts worry an unprecedented number of ballots could be disqualified this cycle. Research has found that first-time mail-in voters are up to three times more likely to have their ballot rejected compared to experienced mail-in voters. Studies also show that people of color and young people are more likely to have their ballots rejected.

Enter “notice and cure” processes, which advocates argue are an essential part of any vote-by-mail system that help protect voters’ rights to due process. “Notice and cure” processes require that voters be informed if their ballot has been rejected, and gives voters a chance to correct any mistake they may have made. “It’s very, very important — understanding that these are the dynamics of the election — that we put something in place that actually allows people to preserve their vote,” says Celina Stewart, chief counsel and senior director of advocacy and litigation at the League of Women Voters, which has won several lawsuits requiring states to implement cure processes.

“Just as we are making changes to our election laws… to account for COVID, we also need to account for first-time voters or people using this avenue for the first time,” argues Sylvia Albert, the director of voting and elections at the advocacy organization Common Cause.

Here’s what to know about correcting mail-in ballots in the upcoming election.

What causes mail-in ballots to be disqualified?

This varies widely, depending on how strict a state’s vote-by-mail laws are. Voting by mail can be confusing, especially for voters who haven’t done it before.

“Many states have arcane technical requirements that aren’t communicated well,” explains Charles Stewart, a professor of political science at MIT. Some states, such as Missouri, require voters to notarize their mail-in ballots; others require at least one adult witness to sign the ballot. Some states, like New Hampshire, require voters to place their ballot in a “secrecy sleeve” that goes inside the pre-addressed envelope provided. Kentucky requires voters to also sign said sleeve. Failure to complete any of these tasks could result in a ballot being disqualified. (The ACLU has a guide on each state’s vote-by-mail requirements.)

Ballots can also be disqualified due to signature mismatch. At least 31 states use signature matching to verify absentee ballots, per the Campaign Legal Center, meaning they compare the signature on a voter’s ballot to the signature the Board of Elections has on file or the signature on the absentee ballot request form. The mechanics of this process can vary across—and even within—states. Some jurisdictions use computers for a first round of checking, while others leave the process up to the discretion of local election officials, says Barry Burden, a professor of political science and the director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“I think there are real concerns about the quality of the process and exactly what signatures the state has on file to compare against,” says Burden. Many voters’ signatures were taken at the DMV on digital signing pads, which are notoriously glitchy. Some signatures are old, and could have been taken 20 years ago when a person first registered to vote.

Signature rejections are also “not distributed equally across the population,” Burden says. According to the Campaign Legal Center, voters with disabilities, non-native English speakers, racial minorities and the elderly are more likely to have ballots rejected because of signature match issues. Studies also show that young people—who on average don’t have as reliable signatures—are also more likely to have their ballots rejected because of a mismatched signature.

That’s what happened to 20-year-old Isabelle Halbe-Sauer, who voted for the first time in the 2018 Arizona midterms. She cast her ballot by mail while attending Arizona State University, and shortly afterwards received a call from an elections official notifying her that her signatures didn’t match and asked her to verify her identity, which she did. Like many young people, Halbe-Sauer says she has “never had a very consistent signature.”

But signature mismatch can also impact more experienced voters, such as former Florida Rep. Patrick E. Murphy. During the 2018 Florida midterms, Murphy saw on the news that ballots weren’t being counted because of signature mismatch and went online to check the status of his mail-in ballot. Sure enough, he saw it was labeled invalid. He was shocked. “I’ve had the same signature since I was 16,” he says. Murphy ended up curing his ballot by going in-person to the county elections office and signing an affidavit, but was alarmed it could have been disqualified. “There’s got to be a better way to do this, a better way to make sure your vote counts,” he says.

How can voters fix mistakes on mail-in ballots?

This also depends on the state. In a state with a “notice and cure” process, voters should be notified by a local elections official if there’s an issue with their ballot. (Here is The Voting Rights Lab’s list of states with cure processes.)

The way voters are notified depends on what information the state has on file. Some states require voters to provide a phone number or email. (Arizona, for example, allows voters to sign up for text message alerts.) Others only have voters’ physical addresses and send letters by mail notifying them of the issue.

How ballots are cured also varies state to state. Some states simply let voters know their ballots were rejected and ask them to cast a new one. Others ask voters to provide evidence of their identity, sometimes requiring them to come in-person to the county elections office, to validate the ballot.

“There’s no uniform standard across the country on how this is done,” says Stewart of the League of Women Voters. “There is a lot of levity given to board of elections officials, from secretaries of states, on how to handle it based on their particular jurisdiction and what works in that particular jurisdiction.”

The most effective curing systems give voters ample time to fix the problem once they’ve been notified, says Sophia Lakin, the deputy director of the Voting Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). In Illinois, for example, voters have until 14 days after the election to fix an issue with a ballot.

But many states don’t give voters that much time. Florida, for example, allows voters to cure a ballot up to 46 hours after the election. In those tight windows, if a voter doesn’t provide a phone number or email address with their ballot and returns their envelope on Election Day, it would be extremely difficult to be notified by mail in time to fix the ballot, explains Daniel A. Smith, a professor and chair of political science at the University of Florida. To be safe, advocates urge voters to cast their mail-in ballots as soon as possible to provide plenty of time for any potential problems to be flagged and fixed.

After Laura Jantzen voted by mail in Montana in 2016, she says she was notified that she needed to go to the county elections office and cure her ballot because of a signature issue. She was able to quickly get there before the deadline on Election Day. But, the 37-year-old says, while she found the process to be straightforward, it would have been harder if she had less flexible work hours, or needed to find childcare. “If I was in a different situation, which I know many voters are, I could see that process as being a lot more challenging and potentially not doable,” she says.

What happens in states that don’t have a “cure” process?

In states without a “notice and cure” process, if a ballot is disqualified, it will likely be thrown out, sometimes without the voter’s knowledge. But even in these states, there are some steps for voters to take to protect against this.

While 21 states still don’t have state-wide cure processes, some individual jurisdictions have taken it upon themselves to implement their own system, so voters should check with their local officials to see what’s available in their area, recommends Megan Lewis, the executive director of Voting Rights Lab.

For voters living in one of the many states that allows them to track mail-in ballots, advocates recommend they track it every step of the way to see if their ballot was flagged as having an issue. If that happens, a voter can call their local election officials to see if there’s any way to fix it, or potentially spoil, or throw out, that ballot and cast a new one, adds Stewart of the League of Women Voters.

Is the movement to push for more states to adopt a “cure” process making progress?

Over the past several years political and legal pressure has driven more and more states to adopt cure systems. This year alone, advocates have filed at least 18 lawsuits to force states to implement cure systems before the general election, according to a tally by Loyola Law School Professor Justin Levitt. In general, “the courts have decided in favor of cure,” says Stewart of MIT.

Traditional absentee ballot law operated under the legal theory that absentee ballots are a convenience and not a right, and for that reason, “all of the risk of voting an absentee ballot was born by the voter,” says Stewart. Under that reasoning, the state could impose restrictions and it’d be up to the voter to adhere to them. But as more states have moved to vote by mail systems—especially given the constraints of the pandemic—that theory has weakened, says Stewart.

Most of lawsuits filed this year argue that denying voters the opportunity to correct problems with their ballots deprives them of their right to due process, especially in the instance of signature mismatch, which is often so subjective. Over the past several months at least six federal district courts—North Dakota, North Carolina, Indiana, Texas, Pennsylvania and New Jersey—have ruled in agreement.

But several states’ cure processes are still wrapped up in legal battles, so advocates recommend voters check with their local election officials for the latest developments, and proactively check the status of their ballots throughout the process of voting if they can. As Stewart put it, “don’t make any assumptions about whether your ballot is going to be going to be approved.”

It can take perseverance. Miltrine Jenkins Barden has been voting since she was 18, since she marched in the 1960s Civil Rights Movement and went to jail for three days for the right to cast a ballot. But the 74-year-old had never voted by mail until September, when she filled out her first mail-in ballot from her Greensboro, N.C., home out of concern about the COVID-19 pandemic.

A few days later, Barden says she received a call from the North Carolina Democratic Party’s Voter Assistance Hotline informing her that her ballot had been marked invalid because she’d left off a required witness signature. (Barden says she thought the signature was only required if you needed assistance filling out a ballot.) She says she was told the Board of Elections would send instructions on a “cure certification” process, but instructions never came. She later found out her ballot was one of thousands that were in limbo as the legal battle over North Carolina’s cure process continued to play out.

After repeatedly calling her local Board of Elections, Barden eventually decided to “spoil,” or throw out, her original ballot and cast a new one. Barden says she’s frustrated that the process wasn’t easier. “There should not be any kind of obstruction,” she says. “It is our right and our privilege to vote.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Madeleine Carlisle at madeleine.carlisle@time.com