In late July, the Arizona Coalition to End Jail-Based Disenfranchisement, a local voting advocacy organization, mailed a small, white postcard to each person detained at the Apache County Jail in St. John’s, Arizona. It read: “BEING IN JAIL DOES NOT AFFECT YOUR RIGHT TO VOTE,” and provided information about voter eligibility and how to request a ballot from a corrections officer.

A couple of days later, according to two men incarcerated at the jail, a corrections officer asked detainees to return their postcards. One of those men says the officer explained that his commander had asked for the postcards back. A third says that at least two other detainees told him that a corrections officer had taken their postcards as well.

“I just handed it to them, surprised,” says Christian Nasse, a 66-year-old detainee at the jail. “And just put it in the memory bank that it was odd — another intimidation thing.”

Nasse, who is being held at the jail pretrial on multiple charges, says by the time his card was taken, he had already requested his ballot. But when he received it, a different corrections officer warned him that he could face more charges if he voted with a prior felony conviction—something that is true in some cases but didn’t apply to Nasse, who is eligible to vote. Nasse said he eventually decided not to cast a ballot because he didn’t want to risk any more legal problems. When asked whether he felt intimidated into making that decision, Nasse said yes.

When asked for comment, Apache County Jail Commander Michael Cirivello said postcards are not allowed in the jail’s housing units “due to the inability to ensure that the cards do not contain contraband without destroying the postcard.” He said a younger staff member had mistakenly allowed the cards into the housing units. (The Arizona Coalition said they were never told of this rule, nor did they see it listed in the jail’s rules for receiving mail.) Cirivello also said detainees are already provided information on voting in the housing unit’s “information cages,” and that “we at the Apache County Jail take [inmates’] right to vote very seriously.”

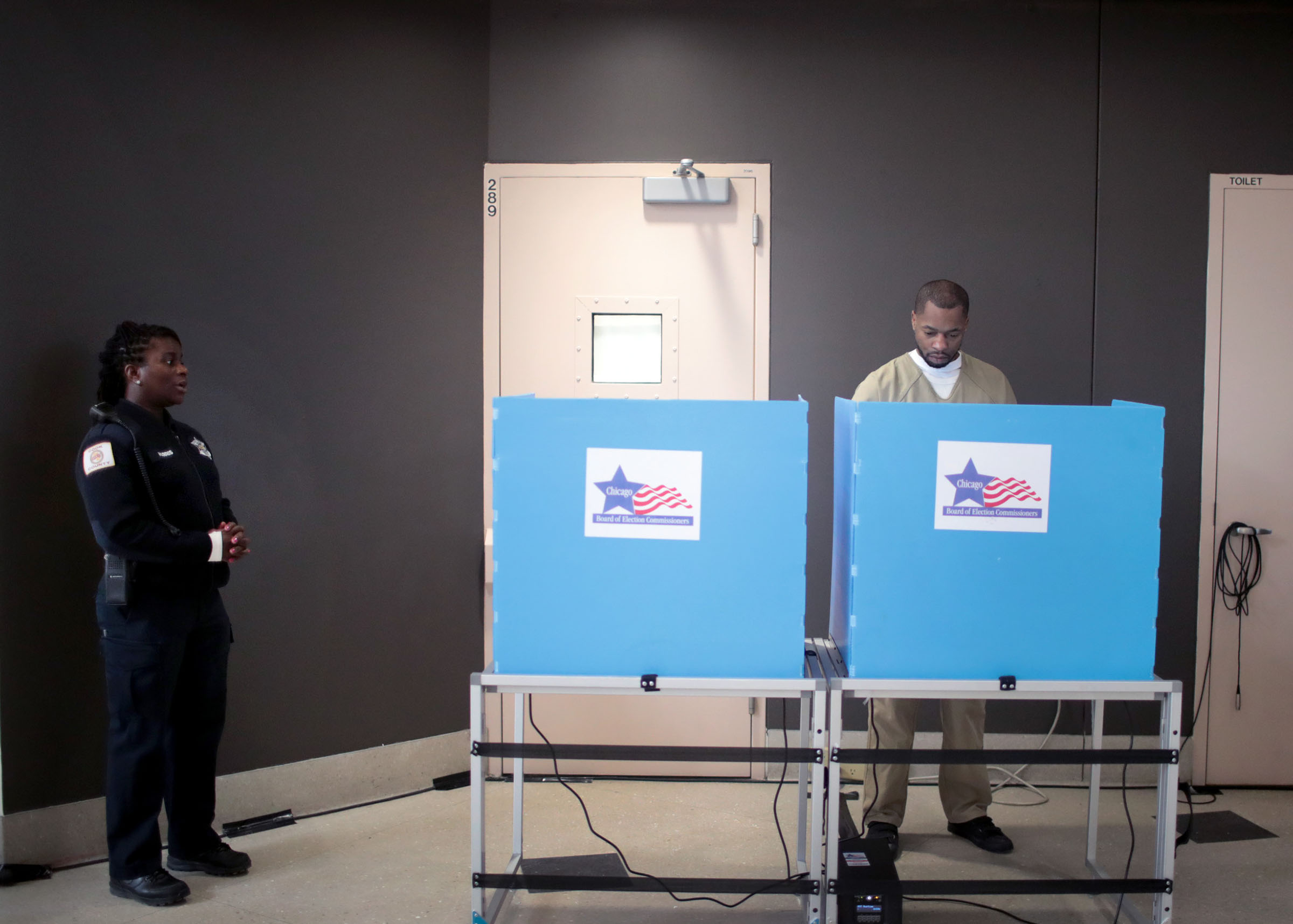

Nasse’s alleged experience trying to vote in Arizona’s Aug. 4 primary offers a small window into the complex set of barriers facing many of the 750,000 people in jail in this country. Like Nasse, most people in U.S. jails are eligible to vote. Many either have yet to stand trial, and so remain innocent in the eyes of the law, or are eligible for other reasons, such as serving time for lesser crimes like misdemeanors.

It’s unclear how widespread voter disenfranchisement is in U.S. jails, but experts worry that the current environment creates a lot of room for error. Many U.S. jails lack voting policies, and are hobbled by major gaps in education on voter eligibility among both detainees and jail employees. While some local authorities are proactive about helping detainees access their ballots, others are not. Jails also generally lack transparency and are out of the public view—a problem that has been compounded during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many jails have suspended or restricted guest visits, including from advocacy groups that would normally visit before an election. “We don’t really know what the full picture is of jail-based disenfranchisement, partly because of this very decentralization,” says Ariel White, an associate professor of political science at M.I.T.

These factors all combine to make access to voting in jails something of a blackbox, with inconsistencies that often render this constitutional right hard to access. It’s a system that disproportionately impacts potential voters of color; for example, according to the Department of Justice, in 2018 Black people were incarcerated in jails at a rate of 592 per 100,000 Black U.S. residents, while white people were incarcerated in jails at a rate of 187 per 100,000 white U.S. residents. Five weeks before a major election, jail populations could make up a significant voting bloc, particularly in local races such as the race for sheriff—the very people who often have the discretion to facilitate voting programs. With the clock running, advocates across the country are scrambling to reach incarcerated people to make sure they have the resources they need to vote.

Sometimes problems with ballot access are only observable when there is a group or advocate serving in a watchdog role, like in Nasse’s case. After learning the postcards it had sent to the jail were confiscated, the Arizona Coalition to End Jail-Based Disenfranchisement sent a letter to the Apache County Sheriff and Apache County Jail Commander on Sept. 25, asking the jail to address the reports of alleged disenfranchisement of eligible voters within the facility. “We have received reports indicating not only that Apache County is failing to take the steps necessary to ensure jailed voters can access the ballot, but also that jail staff have actively impeded outside efforts to assist voters held in Apache County Jail,” states the letter, first reported by TIME.

Along with the taking of postcards, the coalition says they have received reports that a voter registration kiosk set up in the jail is dysfunctional, only leading users to a blank text box with no instructions. The group says they reached out to the Sheriff about addressing the issue of voter registration, but have not received a response. Soon, it will be too late: Arizona’s registration deadline is Oct. 5, and the coalition urged the jail to at least make forms available by Sept. 28 and arrange for pick up of the forms by the registration deadline.

Cirivello, the jail’s commander, said the jail has communicated with the county recorder’s office over best voting procedures, trained staff on those procedures, posted information flyers for detainees and taken steps to ensure detainees can request ballots. They also pointed to the fact that the Arizona Advocacy Network & Foundation, a member of the coalition that wrote the letter, graded their jail’s voting policy a “C” in July. Cirivello wrote, “While not a perfect score, it is a passing grade!”

“Where no one is doing anything”

In the 1970s, the Supreme Court ruled eligible voters in jail can’t be denied the right to vote because they’re incarcerated in the case O’Brien v. Skinner. But that doesn’t mean that jailed people are always given an opportunity to exercise that right.

State and local systems governing voting are often inadequate—or simply dysfunctional—when applied to the context of jails, and end up putting a disproportionate burden on detainees to exercise their constitutional rights. For example, in the lead-up to the November 2008 presidential election, two men, Hassan Swann and David Hartfield, who were detained in Georgia at the DeKalb County Jail on misdemeanor convictions, were denied their request to receive absentee ballots at the jail, according to a federal complaint filed by the men. At the time, state law said only disabled voters could receive an absentee ballot to a location within the county other than their permanent mailing address.

The complaint stated that although the jail had put on voter registration drives and provided detainees with absentee ballot requests, country officials didn’t inform Swann and Hartfield that they would not receive their absentee ballots at the jail. The county sent the incarcerated voters’ absentee ballots to their permanent addresses, and jail officials placed a drop box in the jail lobby for family members to drop them off. But Swann and Hartfield never ended up receiving theirs; their complaint stated the absentee ballots never arrived at their permanent addresses. And so the 2008 election came and went without the men casting their ballots.

The lawsuit charged that officials did not help the men find an alternative means to vote, thus violating their Fourteenth Amendment rights. The case never went Swann and Hartfields’ way: Hartfield was dismissed as a plaintiff by the district court, which sided with the state, and an appeals court ordered that the case be dismissed due to an omission Swann left on his absentee ballot application. Georgia did not change its law to allow detainees to receive absentee ballots who were incarcerated in the same county as their permanent address until 2019.

These complicated—and often unsatisfactory—civil cases often do little to move the needle, says Dana Paikowsky, an equal justice works fellow at Campaign Legal Center, one of the advocacy organizations included in the Arizona Coalition to End Jail-Based Disenfranchisement. “[Courts] hold the voter to an extraordinarily high standard to prove that there is a denial, and their analysis is often disconnected from the realities of incarceration,” she says. Incarcerated people are given limited access to information or communication, and many choose to represent themselves because of the cost of an attorney.

Another major problem is that many people in jail don’t have the information they need to advocate for themselves. Many people who have yet to stand trial or who have been found guilty of misdemeanors don’t know they are still eligible to vote. They depend on another party—often the jail itself—to make them aware of it and create pathways to participating. And yet, the systems in place often require that voters not only recognize that they’re eligible to vote, but act proactively and persistently to access their right to the ballot.

An August report by The Appeal, an editorial project by The Justice Collaborative, compared two Georgia counties, DeKalb and Gwinnett County. A batch of emails obtained by American Oversight showed that in designing a voting procedure for detainees subsequent to the 2019 change in Georgia law, a Gwinnett county official told members of the staff that they had been advised “it is the voter’s responsibility to ask for the opportunity to vote in the 2020 election cycle.” A later email emphasized that no special announcements needed to be made. Meanwhile, in DeKalb County, the sheriff had partnered with a local NAACP chapter to run a voter registration drive in the county jail.

It’s a case study for how different the process of registering and voting can be in two jails, divided only by a county line. “I think that there are a lot of jurisdictions out there where no one is doing anything,” Paikowsky adds. “Where there aren’t advocates, where the local election official is not engaged and where the sheriff is not engaged.”

“My voice should be heard”

Voting advocates agree that one of the best-case scenarios is that people find themselves in a jail with a policy that proactively helps them cast a ballot, or that partners with advocacy organizations like Arizona Coalition to End Jail-Based Disenfranchisement, that help people in jail vote.

Frank Baker, a 43-year-old detainee in Texas’ Harris County Jail, says he didn’t know he was eligible to vote in jail until the Texas-based advocacy group Houston Justice told him so and helped him register. He wishes the jail had a better system in place to inform detainees of their right to vote without needing outside help. “We won’t know [we can vote] unless someone comes in and wants us to vote,” Baker says. “I haven’t been convicted… My voice should be heard, even from the incarcerated state.”

Since the start of their registration efforts at Harris County Jail in 2018, Houston Justice says they have registered over 2,500 voters. The Harris County Sheriff’s Office touts its work with the county clerk’s office and Houston Justice to ensure incarcerated, eligible voters have the opportunity to vote by mail. “It’s a big priority for the Sheriff [Ed Gonzalez] to make sure that everyone who’s eligible to vote has the ability to do [so], and we’ve taken steps that we think are far beyond what any other county jail in Texas is doing,” Jason Spencer, a spokesperson with the Sheriff’s Office, tells TIME.

In Hinds County, Mississippi, the Sheriff’s office has only recently taken an active stance. “Sheriffs for the most part are pretty much policy makers, and so there’s no set rulebook, so to speak, that’s going to regulate what every sheriff in the United States has to do,” says Lee Vance, the Sheriff of Hinds County. Since Vance’s tenure began earlier this year, voting processes have been set up for incarcerated people at his jail. Before that, the county didn’t have a system in place. “I thought that wasn’t fair nor was it acceptable.”

Advocates say it’s exactly that individual subjectivity that creates such unpredictable and patchy access to voting between corrections facilities. Amani Sawari, who coordinates the Right2Vote Campaign, a national campaign that highlights marginalized voices of incarcerated people, has run into this problem before. She said, for example, that when she contacted the Kent County jail in Michigan, jail staff told her that “inmates don’t vote here,” even after acknowledging to her that pretrial detainees were being held at the jail.

In response to an inquiry on the call and the jail’s voting policies, Kent County Correctional Facility Captain Klint Thorne said the “inmate handbook” gives incarcerated people awaiting arraignment guidance on how to request an absentee ballot application, and he said the jail had recently partnered with a local advocacy group to help get eligible voters in their jail registered. “Without more information available to identify the staff member and follow up with them directly for more details, it is difficult to fully comment on the context of that phone conversation,” he wrote in an email, adding “eligible inmates are able to request an absentee ballot while confined.”

The Arizona Coalition to End Jail-Based Disenfranchisement, which sent the postcards to Apache County Jail, works across the state to fill these kinds of gaps. Adrienne Carmack, the deputy director of Arizona Advocacy Network & Foundation, a member of the coalition, says that even after developing jail-based voting procedures in partnership with the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office in the fall of 2019, it was months before the Sheriff’s Office made time to meet with them.

When The Arizona Coalition and the Sheriff’s Office finally did sit down in January, the Coalition was told that there wasn’t enough time to implement the procedures before the March presidential primary. (A report released by the Arizona Coalition in July found that of the 2,700 Democratic voters the group estimated were in Arizona jails in March who would have been eligible to cast a ballot in the Democratic presidential primary, only seven people voted.) Since then, the Coalition says, the Sheriff’s Office has been uncooperative about adopting their voting plan.

When asked for comment, the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office said it has updated its election “information and awareness efforts” through the use of tablets in the jail in partnership with the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office and Elections Department. “MCSO always has and will continue our support of those who wish to exercise their constitutional right to take part in the election process,” the Sheriff’s Office said.

It’s impossible to know what every jail across the country is or isn’t doing to help detainees access the vote in the days ahead of this critical election. And that, advocates say, is why better state policies need to be implemented so something as fundamental as the constitutional right to vote isn’t left up to the priorities of one jail’s administration.

“In some cases it’s not necessarily malice, it’s about priorities,” says Christopher Uggen, a professor of sociology and law at the University of Minnesota and the co-author of Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy. “[It] is jarring to think that something as fundamental as the right to vote can come down to essentially the whim of a [local] official,” he says. “That’s not the way voting is supposed to work.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Madeleine Carlisle at madeleine.carlisle@time.com and Lissandra Villa at lissandra.villa@time.com