From the bridge of the Arctic Sunrise, an old ice-breaking fishing trawler turned research vessel now plying the polar waters between Greenland and northern Norway, Laura Meller has an unparalleled view of our planet’s future. It is both gorgeous, and terrifying. The early autumn sunlight bathes the scattered icebergs in soft pink and orange hues that glimmer with the gentle swell.

“It is so soft and quiet out here that it’s difficult to remember that we are literally looking at a climate emergency unfolding before our eyes,” she says by satellite-enabled WhatsApp. Meller is a polar advisor for a Greenpeace expedition plying the edge of the polar ice cap to document the minimum extent of sea ice this year, a potent indicator for overall global climate health. The prognosis is grim.

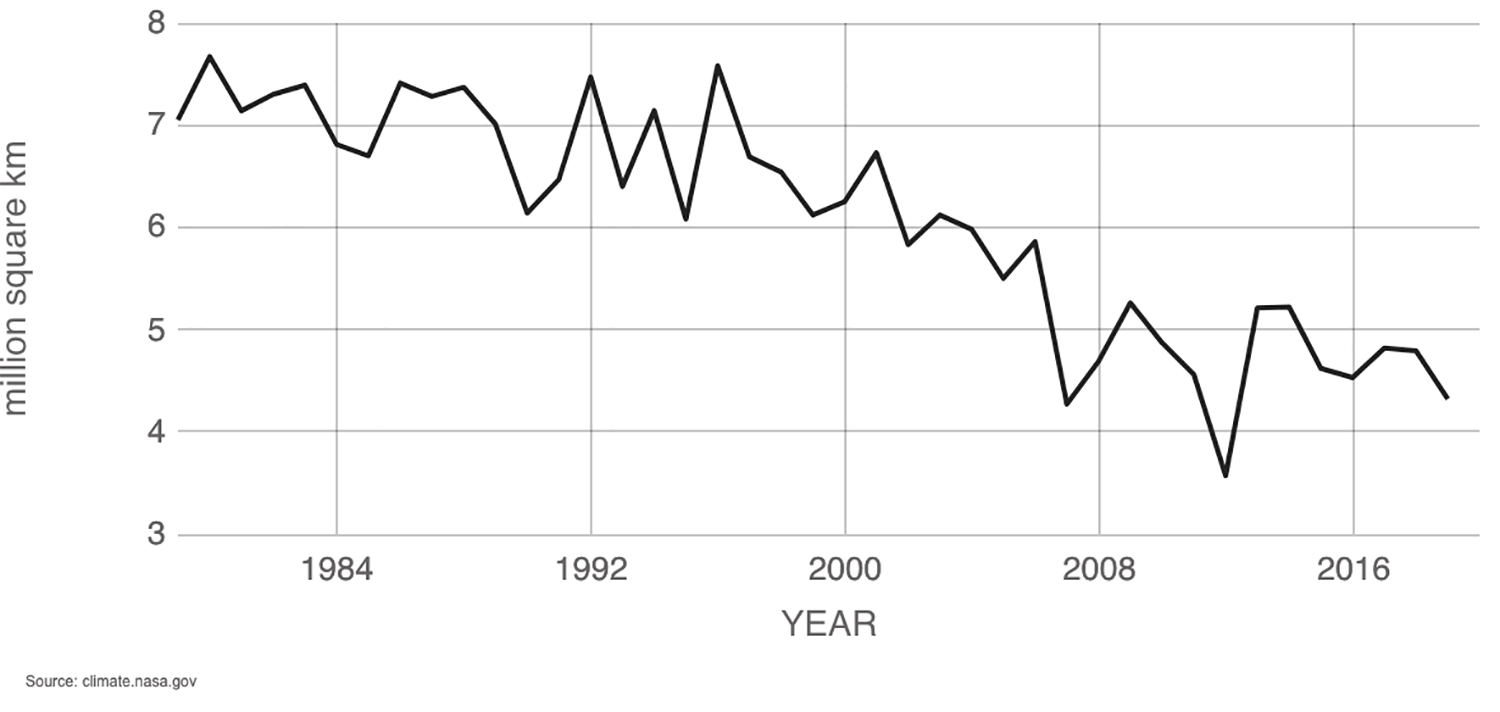

On Sept.21, scientists at the United States-based National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC), announced that Arctic sea ice coverage had contracted to a near-unprecedented minimum of 3.74 million square kilometers on Sept. 15, the second lowest in 42 years of records. Arctic sea ice has already lost two-thirds of its volume over the past four decades, part of an alarming trend in polar warming that that is already seeing impacts across the globe. “It is a traumatic picture,” says Meller, of the satellite images provided by NASA that the NSIDC used to make its assessment. “The rapid disappearance of sea ice is a sobering indicator of how closely our planet is circling the drain.”

Polar sea ice minimums—the extent that ice melts during the summer months before starting to form again as winter returns— are not merely a problem for polar bears and Inuit hunters who rely on ice to preserve their traditions and culture. When there isn’t enough ice to reflect the sun’s rays back into space, that heat is instead absorbed by the ocean, accelerating further ice melt while altering ocean currents, weakening the jet stream and changing wind patterns. The effects ripple through the global ecosystem, manifesting in greater drought, heat, floods and storms. While this year’s record breaking wildfire season in the U.S., or the series of hurricanes wreaking havoc in the country’s south, cannot be directly linked to this year’s near-record loss of ice in the Arctic, they are all symptoms of the same ailment: increasing carbon emissions.

The symptoms are also apparent elsewhere in the northern polar region. On Sept. 14, just a day before the Arctic officially reached its minimum level of ice cover, The Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland reported that Greenland’s largest remaining ice shelf had just jettisoned a chunk of ice twice the size of Manhattan. The Arctic Sunrise was too far away to see the glacier break apart, but the resulting flotilla of icebergs could easily be spotted on satellite images. “Such a massive piece of ice collapsing into the ocean like that—the planet doesn’t really have much more powerful ways of alerting us to the crisis,” says Meller.

It’s the second year in a row that Greenland’s glaciers have seen record losses of ice; overall, the region has warmed by an average of about 3C since 1980, resulting in unprecedented levels of melting. New research published in the journal Nature Communications Earth & Environment last month indicates that Greenland’s melting ice sheet has already passed the point of no return. Even if the climate were to stop warming today, researchers found, the glaciers will continue to melt for some time.

Meanwhile, another study published in the journal Nature Climate Change, says that the effects of global warming in the Arctic are so severe that the climate there is already shifting from one dominated by ice and snow to one characterized by open water and rain. The beginnings of that transition can already be seen from space.

Satellites have been taking snapshots of Arctic sea ice since 1979, and ice coverage had been declining by about 12 percent per decade, until 2007, when it started accelerating into near record lows almost every year. The year 2012 saw the least amount of ice, but 2020 is a close second, says Twila Moon, the deputy lead scientist at the NSIDC. “We should be thankful for any year we are not seeing a record, but second place is still abysmal and indicative of the completely changed world we are living in.”

Global sea levels are largely unaffected by sea ice melt, as it was already displacing ocean water when frozen. The loss of land based glaciers and ice shelves, however, has serious consequences. Were it to melt entirely, Greenland’s ice sheet could raise sea levels by at least 20 feet (6 meters), putting many of the worlds’ coastal cities under water. Even at current rates of warming that eventuality is still a few centuries away. But when the sea ice disappears, it can accelerate the loss of land-based ice as well, by pulling out the stoppers that keep it locked up on shore, says Moon.

Scientists estimate that meltwater running off the Greenland ice sheet in 2019 was enough to raise global sea levels by more than 2 mm. It may not sound like much, but over time it is enough to flood low-lying islands and cities, especially combined with storm surges and high tides. “Our ice sheets, our glaciers, they are all holding water that would otherwise be in the ocean,” says Moon. “The more rapidly we warm the climate, the more rapidly we lose the ice, and the more rapidly it moves to our shores.”

The solution, she says, is as obvious as it is difficult: stop the rate of fossil fuel emissions. “If we take decisive action now, we can slow the rate of ice loss, we can slow the rate of changing water levels, we can slow coastal erosion and flooding. And that gives us more time to adjust to the changes that already are coming.”

Even if carbon emissions were to somehow to end today, much of the Arctic’s ice melt would stay locked in for years to come, the result of global warming over the past few decades. That’s all the more reason to act now, Moon says. “We are behind the curve of how we are going to adapt to sea level rise that is already coming from past actions, and if we continue with this pace of emissions, we will have even more to catch up to.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com