Nigel Alexander Clay hadn’t planned on voting. He’d been detained in Arlington, Va. for misdemeanor charges since late summer 2019, and didn’t think voting from jail was possible. So when Chris DeRosa, the Arlington chapter leader of the advocacy group Spread The Vote came to the jail to ask if any detainees wanted to register to vote in Virginia’s 2019 elections, Clay jumped at the chance.

“Being in jail, it’s easy to think, ‘Man I don’t matter. The world is moving on without me,’” the 28-year-old tells TIME. “Having my voice heard and having my vote counted… just having that option is a beautiful thing.”

Clay researched the candidates running in Virginia’s 2019 elections, including the local commonwealth attorney, sheriff and county board members, filled out his mail-in ballot, returned it, then called his local registrar’s office to confirm it’d been received. “It just gave me some hope,” Clay says. “Even though [you’re] going through some tough times… don’t forget you can still vote. This is a democracy.”

Spread the Vote has now partnered with more than 50 jails across the U.S. in a broad new initiative, Vote By Mail in Jail, which is organized in partnership with the nonprofit Vote.org. The advocacy group has more than 150 volunteers researching jails’ voting infrastructure, training jail program officers and counselors on how to facilitate vote by mail, and sending postcards to incarcerated people explaining how to cast their ballot in 18 states. The organization aims to reach 15,000 people in 300 jails across more than 25 states by the general election on November 3.

Other groups are doing similar work across the country. In Wisconsin, the non-profit All Voting is Local and ACLU of Wisconsin analyzed vote from jail policies and presented recommendations to county sheriffs and clerks across the state. In Illinois, voting access advocacy organizations, including Chicago Votes, have successfully pushed for legislation that makes ballots more accessible in jails throughout the state.

But advocates say they’re still in the early stages of a long battle. Across the country, there’s little consistency, or oversight, of jail voting, and the roughly 750,000 people in U.S. jails represent one of the most often-overlooked and difficult-to-reach populations, especially in places where law enforcement is uncooperative or misinformed. The majority of those in jail have not been convicted of felonies, and are therefore eligible to vote, and many are behind bars simply because they cannot afford bail for minor offenses. Their access to the ballot is blocked not by legal issues, but logistical ones. Because a disproportionate makeup of jail populations are people of color, this disproportionately marginalizes them as voters in this context as well.

This de facto disenfranchisement can affect more than these individuals’ lives. Especially in close contests, voters in jail can determine the outcome of local races for sheriffs and judges, who enforce and interpret policies that directly affect the lives of the incarcerated.

Much of the national conversation around criminal justice reform and voting in recent years has focused on those with felony convictions. It’s only recently that reform measures aimed at voters in jail, who are often serving time for misdemeanors, began gaining traction. “As the community of reformers expanded, people kept searching for the ripple effects of mass incarceration,” says Marc Mauer, senior adviser to The Sentencing Project, a criminal justice reform advocacy group. “And increasingly there’s heightened discussion about the jail voting issue along with that.”

“It definitely will open your eyes”

Jen Dean, the co-deputy director of Chicago Votes, a voting-access advocacy group, remembers talking with a woman at Cook County Jail in March 2018 who was waiting to vote for the first time in her life. The woman told her that she never would have voted had she not been in jail, and that she couldn’t wait to get out so she could register her whole family to vote, too, Dean recalls. Dean had registered the woman to vote and had been with her when she requested her absentee ballot.

When Dean returned for subsequent voter registration drives, this same woman had been her division’s “gatekeeper”—the person who helps command the room’s attention. All right ladies, calm down, give her the floor, everybody be quiet. The gatekeeper is often instrumental in helping an advocate like Dean present the case for why voting is important. “I will never forget her. She just validated everything that I do, from…voter registration through actually submitting your ballot when you are in the worst environment in the world but you still give a shit for some reason,” says Dean. “That is everything.”

Chicago Votes has registered eligible voters in Cook County Jail, one of the largest jails in the U.S. with a daily jail population of more than 5,000 people, through its Unlock Civics initiative since 2017. According to Chicago Votes, roughly 100,000 people pass through the facility each year and more than 90% of them are eligible to vote. Over the years, the voting-access group has worked with jail administrators to increase access to voter education, registration, and ballot access; set up processes for registering and voting; and trained teams of volunteers on everything from cultural sensitivity, like what language they should use, to serving as poll watchers.

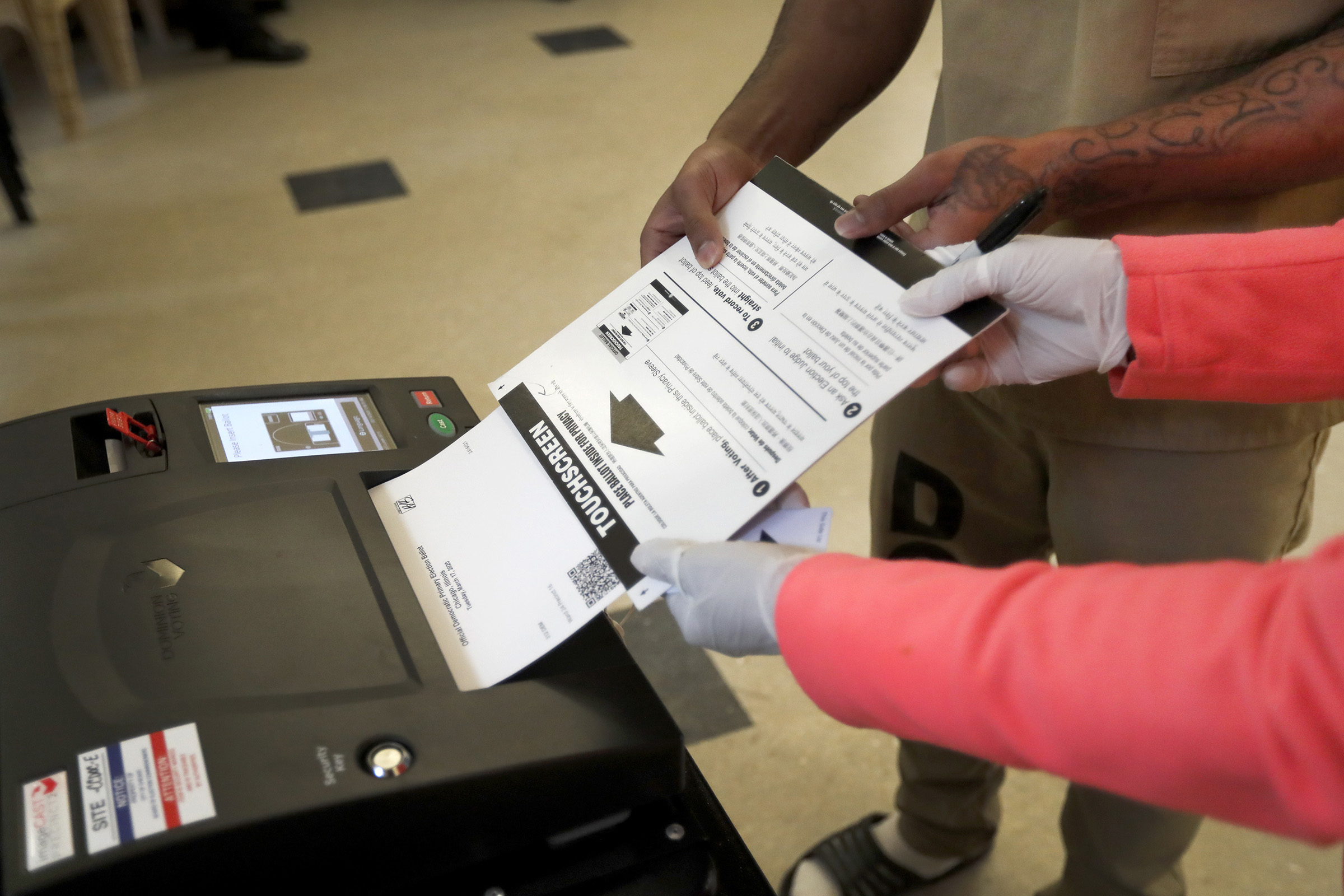

But there were still gaps that needed to be addressed. Illinois switched to same-day voter registration in 2014, but incarcerated people at the jail weren’t offered that access, and if they were arrested after the absentee ballot deadline, they could be disenfranchised. To address those problems, Chicago Votes—backed by a coalition of voting access and criminal justice reform groups—succeeded in pushing the state legislature to pass a bill in 2019 requiring jails across the state to facilitate vote by mail and turning Cook County Jail into an official polling location. It was the first jail in the U.S. to do so.

Sean Allen, 36, who was incarcerated at Cook County Jail pretrial—and voted from there both in the 2018 midterms and the 2020 primary—said the transformation has been meaningful. “Jail [makes] you look at who is the state’s attorney, who is the sheriff of the county, and of course the different laws,” Allen says. “I won’t say for everybody, but it definitely will open your eyes as far as who you’re voting for and what’s going on.”

Due to the COVID pandemic, jail administrators have limited visitors and internal programs in recent months. That includes voter registration, a matter of concern for Dean. “I am definitely concerned about the fact that nobody has been inside that jail doing voter registration this whole summer, and we have an election coming up in November,” she says.

A “cross-section of historically marginalized voters”

In 1974, the U.S. Supreme Court case O’Brien v. Skinner ruled that eligible voters in jail can’t be denied the right to vote because they’re incarcerated. But the Court largely left it up to states and municipalities to figure out how to ensure people in jail could vote. And since the 1970s, says Dana Paikowsky, a fellow at the nonprofit the Campaign Legal Center (CLC), that hasn’t really happened. There have been “very few instances of action being taken to affirmatively address jail-based disenfranchisement at a state level and even locally,” she says.

That is, in part, the problem that voting access advocates are facing in Wisconsin. A county jail analysis published by All Voting is Local and ACLU of Wisconsin found that more than half of Wisconsin counties that responded to their inquiries did not have written policies for how incarcerated people could register and vote, and only one—Kenosha County—had systems in place to make that happen. None of the counties that responded to the advocacy groups’ requests for information said they had a way to track when people in jail asked to register to vote.

Shauntay Nelson, the Wisconsin state director for All Voting is Local, says her group has been in talks with Wisconsin county jails to determine whether they would be able to get lawyers or election officials — what the group calls a “jail voting social worker” — to administer the voting process behind bars. The organization also offers a training program that enables volunteers to pursue voter registration at local jails.

Counties’ failure to proactively offer people in jail access to registration and balloting has an inordinate impact on people of color and the poor. “When you’re talking about who is in American jails, you’re also talking about a sort of cross-section of historically marginalized voters,” says Paikowsky, who works on CLC’s initiative to help facilitate voting in jails across the country. Jail populations are disproportionately Black, Latino and Native American, and disproportionately homeless and low income, she adds. The median bail for felonies is $10,000, or around eight months of income for the typical person detained in jail, according to a report from the criminal justice reform think tank the Prison Policy Initiative.

Enfranchising people in jail is about more than just securing an individual’s right, Nelson argues. “When an eligible voter is denied the fundamental right to vote, not only is their voice silenced, but also the voices of their families and their communities,” she says. “It further alienates these communities from a political process that’s supposed to work for them.”

The power of a few thousand voices

Voting access organizations say they see both good news and bad news on the horizon. On the local level, there seems to be rising interest in the issue, as more volunteers look to get involved, says Jennifer Costa, the director of volunteer training at Spread the Vote. Some days, she says, she receives more than 100 calls from volunteers.

On the national level, the challenges remain formidable. Garien Gatewood, the program director of the advocacy group the Illinois Justice Project, which backed the Illinois legislation to facilitate jail-based voting, says that much of their work is stymied by a lack of a national conversation around the issue. The work being done in Illinois could easily serve as a model for other states, he says, but there’s no national coordination. “There is a leadership vacuum in getting this ball rolling on the national perspective,” he says.

But the path forward is clear, advocates say: states should establish polling places in jails to allow Election Day voting (as Cook County Jail has done); mail voting should be made more widely available; consistent voter education and registration should become the norm; and states should implement oversight measures. Kat Calvin, the founder and executive director of Spread the Vote, says there’s no good reason people in jail should not have the same access to the ballot as anyone else. “They’re being counted in the census. They’re still citizens and there’s no reason that they shouldn’t be able to vote,” she says. “Their lives are being controlled by the system. They should be allowed to elect people in that system. And yet we have the exact opposite of that.”

Jail populations could also be deciding factors in many local elections. In a 2019 article published in the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, Paikowsky of the Campaign Legal Center looked closely at La Plata County, Co., which has a population of around 51,000. She found that a 2014 Colorado House of Representatives race had been decided by just 168 votes and a 2016 Colorado State Board of Education primary had been decided by just 51 votes. The population of La Plata County Jail — which included 142 eligible voters in August of 2016, according to The Durango Herald — could have made a difference in that outcome. Yet Paikowsky found that only one voter had cast a ballot from the jail in the past 20 years.

Wisconsin, an important swing state, is in a similar situation. Wisconsin’s jail population of about 12,500, most of whom are eligible to vote, could add up: As the All Voting is Local and ACLU of Wisconsin report notes, the state swung for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in 2016 by just over 22,500 votes.

Clay, the 28-year-old who has since been released from the Arlington, Va., jail, says that for him, the act of voting is clarifying. While in jail, “it’s easy to get depressed and lose sight of what’s going on,” he says. But casting a ballot, he says, ‘[helped] zoom my perspective out for the bigger picture: that it’s very important, even if you’re in jail, wherever you are, to vote.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Madeleine Carlisle at madeleine.carlisle@time.com and Lissandra Villa at lissandra.villa@time.com