Around the world, students are returning to school as countries experiment with new educational models and social distancing protocols to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

While preliminary research suggests children are less vulnerable to COVID-19 than adults, there remain concerns that schools will become breeding grounds for infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has cautioned that “full sized, in-person classes, activities and events” will likely lead to the spread of COVID-19 in schools. Opening schools in some countries has already proven to be hazardous. In Israel, for instance, schools were the second-highest places for infection for the month of June, after 2,026 students, teachers and staff tested positive for COVID-19.

But as the pandemic enters its sixth month, governments are grappling with how to provide a quality education to children in the midst of an ongoing, long-term crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic has created “the largest disruption of education systems in history,” according to the United Nations, affecting nearly 1.6 billion students in over 190 countries. Some 94% of the world’s student population has been impacted and in low and middle-income countries, 99% of students have been affected. School closures caused by the pandemic have exacerbated previously existing educational inequality, according to a Human Rights Watch report.

In Europe, where some students have been back at school for over a month, countries are experimenting with new strategies for teaching that keep children safe from infection while ensuring they receive a quality education. Here’s how three are reopening schools—and what obstacles they are facing along the way:

Germany

On Aug. 7, 152,700 students at 563 schools returned to school for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic caused a nationwide lockdown in March. Like in the United States, summer vacations are not uniform throughout the country, meaning that schools have been slowly reopening throughout Germany over the past few weeks.

But returning to school looks different this year, with students divided up into “cohorts” of several hundred students. Cohorts are prohibited from mixing with one another and teachers are assigned to specific cohorts. The goal of the “cohort” model is to prevent entire student bodies from needing to quarantine in the case of an outbreak.

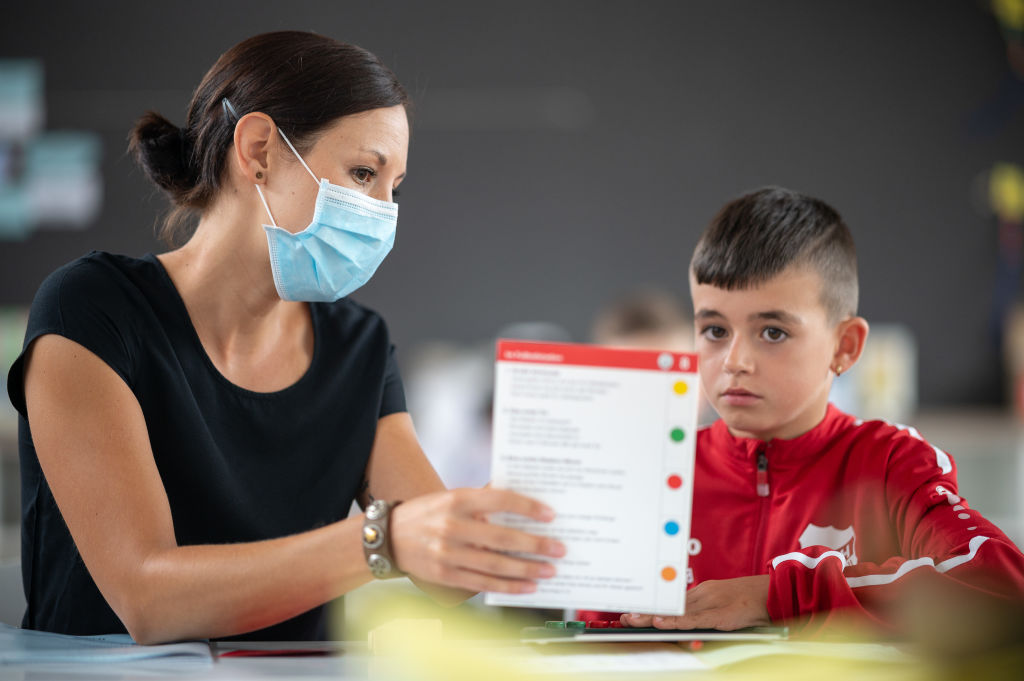

Even within their “cohorts,” students are required to wear face masks in hallways and when entering classrooms but can take them off once seated at their desks. They are also advised to keep their hands off of any banisters and are required to wash their hands regularly. Classrooms have been reconfigured to allow for social distancing and better ventilation.

Although Germany has fast and free testing, effective contact tracing along with lower infection rates than the United States, schools have nevertheless struggled to curb the spread of the virus. In Berlin, one of the first places to reopen schools in the country, at least 42 schools out of the 825 that reopened reported COVID-19 cases within the first two weeks of reopening. Hundreds of students and teachers had to quarantine. Yet despite cases popping up, the country has not yet seen any major outbreaks or long-term school closures.

Although reopening schools has not been easy, Germany plans on prioritizing keeping them open, even if it means closing other public venues. “Children should not become the losers of the pandemic,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel said on Aug. 28.

Scotland

The Scottish government, which has powers over certain domestic policies separate from the U.K. government in Westminster, gave schools the go-ahead to reopen on Aug. 11, advising them to take precautionary measures to prevent the spread of the virus. Like in Germany, Scottish classrooms have been reconfigured to allow social distancing and to increase ventilation. While physical distancing is not enforced between students, pupils showing symptoms are required to get tested immediately.

While Scotland has not seen any major outbreaks in the roughly three weeks since schools reopened, the return to classrooms has not been without challenges. Like in most years, many students have fallen ill with non-COVID, flu-like symptoms which have required them to get tested, overwhelming Scotland’s testing facilities. During the week of Aug. 23, nearly 17,500 people between the ages of 2 and 17 were tested but only 49 were found to have the virus, Scotland’s First Minister Nicolas Sturgeon said at a briefing on Aug. 27. Despite the relatively low number of cases, the Scottish government announced new requirements for students over the age of 12 to wear masks three weeks after schools reopened in order to minimize any potential spread.

For Scotland, keeping schools open remains a priority, with Sturgeon saying there is a “moral and educational imperative that we get children back to school as soon as is safely possible.”

Because Scotland has slowly eased out of lockdown, the government has been able to closely monitor how reopening schools impacts the spread of COVID-19. In contrast, schools in England are reopening at the same time as businesses are encouraged to return to workplaces, which may make it more difficult to monitor where and how the virus is spreading.

Norway

Norway was one of the first countries in Europe to reopen its schools back in April, doing so gradually and with strict social distancing protocols in place. In May, a national ‘traffic light’ model was introduced to guide schools on what infection control measures are to be followed under the pandemic. A ‘green’ light indicates that schools can run according to normal hours whereas a ‘red’ light signifies schools must limit class sizes and alter their school hours according to the size of the outbreak. Since June 2, the traffic light model has been set to ‘yellow’, meaning schools must take measures to reduce physical contact and have stronger hygiene.

Like Germany, Norway has also adopted the “cohort” model, requiring students to arrive at school at staggered times and limiting all interaction between cohorts. While the number of new cases is rising in the region, particularly among young people, Norway has not yet experienced any major outbreaks.

While Norway, Germany and Scotland have all found ways of reopening schools in effective, albeit imperfect, ways, experts worry that the same approach may not be possible in the United States.

“The situation in the U.S. is obviously much more difficult,” says Ralf Reintjes, a professor of Epidemiology and Surveillance at Hamburg University of Applied Sciences. “With regards to the school setting, it’s difficult to be at least slightly optimistic in such a big epidemic to open schools in a normal way.”

Kathryn Edwards, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, agrees. “All of us have read the studies and experiences in Europe. And they seem to have been pretty positive,” Edwards says. “But the burden of disease in European communities is much less than what we’re seeing. Europe has controlled the outbreak in most places more effectively than we have.”

—With reporting by Madeline Roache in London

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com