On March 22, 1977, newly-elected president Jimmy Carter sent a letter to Congress recommending a package of electoral reforms. The president was concerned that America ranked twenty-first in voter participation among the world’s democracies. He argued that the problem was not voter apathy but that “millions of Americans are prevented or discouraged from voting in every election by antiquated and overly restrictive voter registration laws”—a fact proven by the record rates of participation in 1976 in states like Minnesota, Wisconsin, and North Dakota that let voters register on Election Day. Carter recommended same-day registration be adopted universally—tempering concerns that such measures might increase opportunities for fraud by increasing penalties against it to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

He asked for $25 million to help states comply, an expansion to congressional elections of the current system of federal matching funds for presidential campaigns, and closing a loophole in campaign finance law that advantaged rich contenders by allowing them to evade spending limits if they funded their own campaigns. He proposed revising the Hatch Act to allow federal employees “not in sensitive positions” the same rights of political participation as everyone else when not on the job. Most radically, he recommended a constitutional amendment to scrap the Electoral College, which, three times so far, had selected as president a candidate who had received fewer votes than his opponent.

It was among the most sweeping political reform proposals in U.S. history—and soon afterward, legislators from both parties stood together at a news briefing to endorse all or most of it. The bill for universal registration, which RNC chairman Brock called “a Republican concept,” was cosponsored by four Republicans. Senator Baker suggested going even further by making Election Day a national holiday, keeping polls open twenty-four hours, and instituting automatic registration. House minority leader John Rhodes, the conservative disciple of Barry Goldwater, predicted the proposal would pass “in substantially the same form with a lot of Republican support, including my own.”

More democracy: who could object?

The answer was: the New Right, which took their lessons about “electoral reform” from legends of Kennedy beating Nixon via votes received from the cemeteries of Chicago.

The next issue of Human Events, a conservative newspaper, was bannered, “ELECTION ‘REFORM’ PACKAGE: EUTHANASIA FOR THE GOP.” It argued that the current electoral system had never disenfranchised a single citizen—at least “no citizen who cares enough to make the minimal effort.” So why was Carter proposing to change it? Because, Kevin Phillips insisted, it would “blow the Republican Party sky high.” Phillips claimed that Carter had calculated that since he had won Wisconsin by a tiny margin, defying predictions, and since “most electoral analysts credited that upset to the 210,000 allowed to register on election day,” he wanted to expand the scam to all fifty states. A Berkeley political scientist, Human Events noted, predicted national turnout would go up 20 percent under Carter’s reforms—a bad thing, the editors said, because “the bulk of these extra votes will go to Carter’s Democratic Party . . . with blacks and other traditionally Democratic voter groups accounting for most of the increase.” Conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation, meanwhile, got out one issue brief arguing that instant registration might allow the “eight million illegal aliens in the U.S.” to vote, and another arguing that it was a mistake to “take for granted that it is desirable to increase the number of people who vote.”

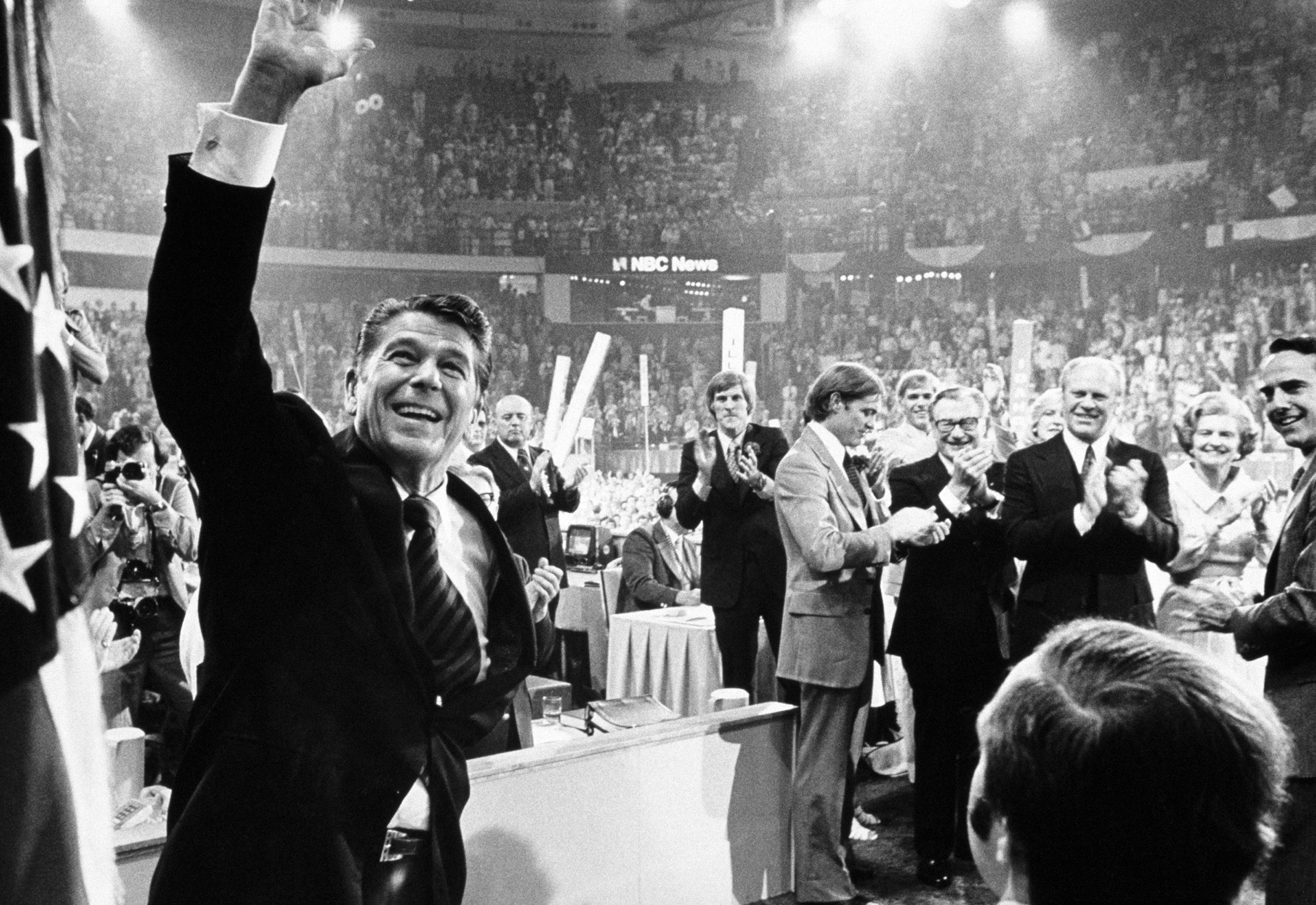

Ronald Reagan had been making similar arguments for years. “Look at the potential for cheating,” he thundered in 1975 when Democrats proposed a system allowing citizens to register by mail. A voter “can be John Doe in Berkeley, and J. F. Doe in the next county, all by saying he intends to live in both places. . . . Yes, it takes a little work to be a voter; it takes some planning to get to the polls or send an absentee ballot . . . that’s a small price to pay for freedom.” He took up the same cudgel shortly after Carter’s inauguration when California adopted easier procedures: “Why don’t we try reverse psychology and make it harder to vote?” Now, following Carter’s electoral reform message, Reagan wrote in his column that what this all was really about was boosting votes from “the bloc comprised of those who get a whole lot more from the federal government in various kinds of income distribution than they contribute to it. . . . Don’t be surprised if an army of election workers—much of it supplied by labor organizations which have managed to exempt themselves from election law restrictions—sweep through metropolitan areas scooping up otherwise apathetic voters and rushing them to the polls to keep the benefit-dispensers in power.”

He added, in a newsletter column on Hatch Act reform, “The intent of the bill seems to be to convert your friendly neighborhood bureaucrat into a machine politician. After all, he does have an interest in keeping government growing”—and if successful it would “render the Republican Party as dead as the dodo bird.” He dedicated a radio broadcast to what he called the most terrifying idea of all: popular election of presidents. “The very basis for our freedom is that we are a federation of sovereign states. Our constitution recognizes that certain rights belong to the states and cannot be infringed upon by the national government.” John C. Calhoun had pioneered that argument in South Carolina in the 1830s, as a way to cloak attempts to preserve slavery in noble constitutional raiment.

And the party establishment soon became convinced.

Republican National Committee Chairman Bill Brock met in Los Angeles with Reagan, who subsequently told supporters that the chairman had assured him “he is opposed to the election reform package,” which “might better be called the Universal Voter Fraud Bill.” Brock then penned an article in the RNC magazine First Monday on the “Democratic Power Grab”; when it had been proposed he called it a “Republican idea.” The RNC passed a resolution claiming that same-day registration would “endanger the integrity of the franchise and open American elections to serious threat of fraud.” Representative John Rhodes, after what the Washington Post called “unremitting opposition for his original stand”—including a cartoon in the Citizens for the Republic newsletter depicting a bleeding GOP elephant stabbed by a figure labeled “Rhodes” and “Universal Registration”—directed his House Republican Policy Committee to adopt a statement of formal opposition.

Several months later, thirty conservatives met in a private dining room at the Capitol Hill Club, the famous “home away from home” for GOP lawmakers, for a ceremony in which Nevada Senator Paul Laxalt, Reagan’s 1976 campaign chairman, and Richard Viguerie, godfather of the New Right, received bronze plaques inscribed, “FOR LEADERSHIP IN PRESERVING FREE ELECTIONS,” for their role in defeating same-day voter registration.

From REAGANLAND: America’s Right Turn 1976-1980 by Rick Perlstein. Copyright © 2020 by Eric S. Perlstein. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com