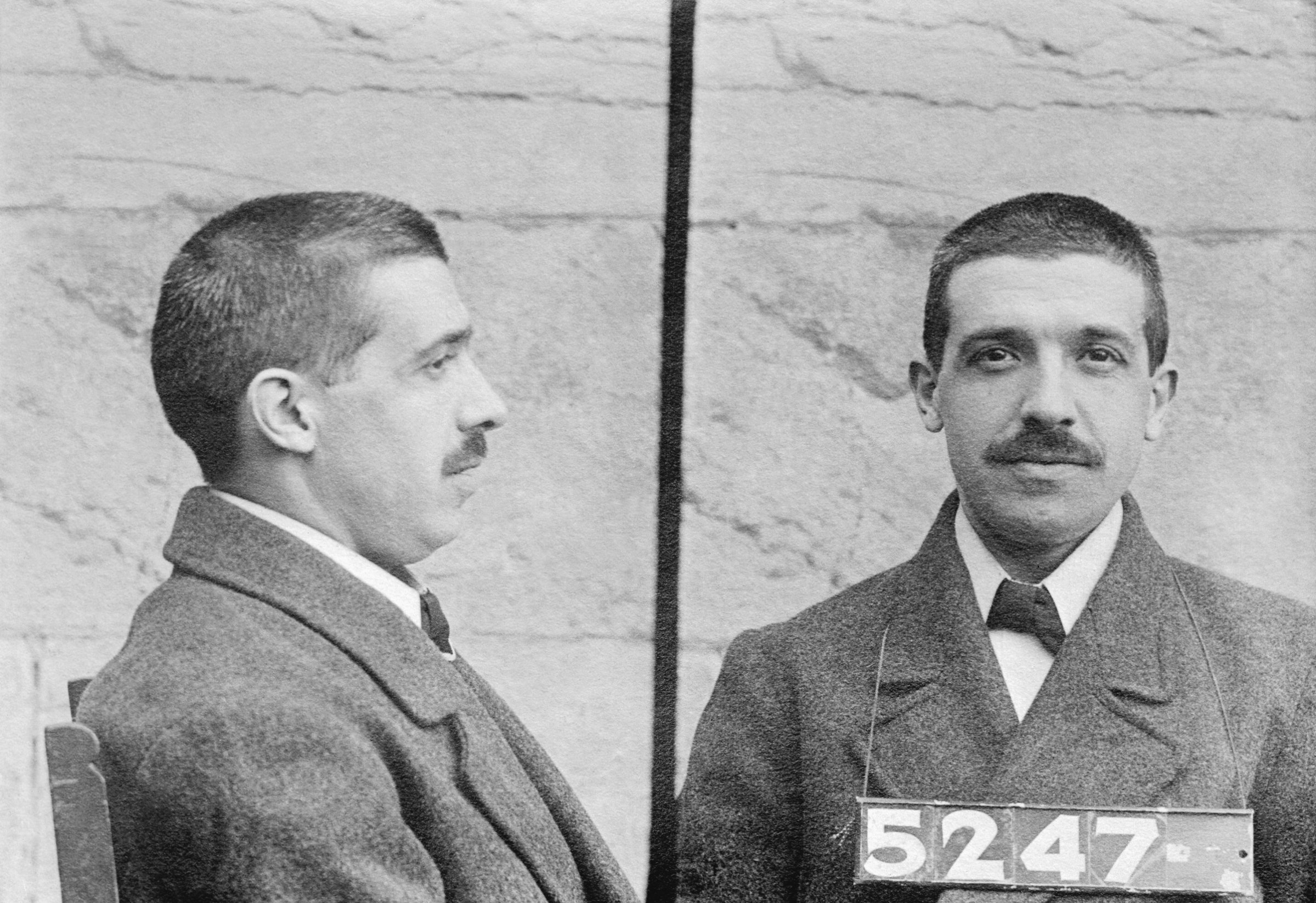

In the century since his arrest on Aug. 12, 1920, Charles Ponzi’s name has been linked to the scam that led to his eventual conviction and imprisonment. At its essence, a Ponzi scheme involves a phony investment in which early investors are paid with the investments of later investors making the enterprise appear legitimate. But Ponzi was neither the first nor the last, by far, to perpetrate this type of fraud.

Ponzi schemes often appear complicated on the surface and Charles Ponzi’s fraud was no different. Ponzi told investors that he was able to take advantage of fluctuating currency values to purchase international postal reply coupons. These were postage vouchers that senders of a letter from one country could include to facilitate a reply from a recipient in another country. Ponzi claimed he could purchase the coupons abroad at a discount and then sell them at face value in the United States at a tremendous profit. Ponzi, like later scammer Bernie Madoff, refused to provide details as to precisely how he operated his investment strategy, claiming he didn’t want to give that information to competitors.

Ponzi promised investors a 50% profit within 45 days and a 100% profit within 90 days—and from all appearances Ponzi was a man of his word, as early investors were rewarded handsomely. Due to what appeared to be his phenomenal success, he soon had investors clamoring for him to take their money. The math, however, just didn’t work. Behind the scenes, Ponzi was only able to pay his investors using money from new investors, not profits. Ponzi was brought down due to a series of investigative reports in the Boston Post newspaper, which ultimately led to a federal criminal investigation resulting in mail fraud charges.

Despite the notoriety of Charles Ponzi, the scheme that carries his name appears to have been first perpetrated by Sarah Howe in Boston in 1879, when she created the Ladies’ Deposit to help invest money for women. According to famed economist John Kenneth Galbraith, “the man who is admired for the ingenuity of his larceny is almost always rediscovering some earlier form of fraud.” As with Ponzi, Howe’s promises of profits were astounding, with promises that investors’ funds would be doubled in a mere nine months. Once again, it was journalists, this time reporters for the Boston Daily Advertiser, who investigated and discovered her scam. She was eventually charged and convicted of her crimes and served three years in prison. Upon being released, she managed to perpetrate an identical scam for two years before getting caught again.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Ponzi schemes share some common characteristics. The high visibility and popularity of their apparently lucrative investments make them appear legitimate. Many Ponzi schemers also appear to be terribly selective in who is allowed to invest with them. This was certainly the case with Sarah Howe, Charles Ponzi and Bernie Madoff. Investors begged these scam artists to take their money. These criminals exploited a rampant fear of missing out on a golden opportunity.

A common theme among Ponzi scheme victims is “irrational exuberance,” a term popularized by former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan whereby people observe others making great profits from investments and determine that this means the investments are safe—even if there are no underlying reasons to support those conclusions. Irrational exuberance is nothing new and certainly was applicable as far back as during the tulipmania of the 1600s in the Netherlands, when speculation in investments in tulip bulbs led to a dramatic market crash in 1637.

Whatever their differences, the same mistake is made by victims of all Ponzi schemes: putting money in an investment that is not completely understood. In a prison interview, Madoff, who stole $50 billion from his victims, even had the chutzpah to blame his victims for their plight, indicating that if they had looked into his investment methodology, they would have seen that it was impossible to consistently earn the returns he claimed to deliver.

So what have we learned since Ponzi was arrested 100 years ago? Seemingly little. Last year U.S. law enforcement discovered 60 major Ponzi schemes, with victims investing $3.25 billion in these totally fraudulent scams. And it is highly likely that the true number of Ponzi scams still being perpetrated is far greater, with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) under the Trump Administration being far less aggressive in its investigation and prosecution of white-collar crime in general and investment fraud in particular.

According to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, “white-collar and corporate prosecutions are at their lowest point in modern U.S. history.” That figure doesn’t mean that white-collar crime isn’t happening. In fact, knowing that the history of Ponzi schemes runs much deeper than that name suggests, perhaps it’s unsurprising that a century hasn’t been long enough to put an end to the scams.

Historians’ perspectives on how the past informs the present

Steve Weisman is a Senior Lecturer in Law, Taxation and Financial Planning at Bentley University in Waltham, Mass. He is also the author and creator of www.scamicide.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com