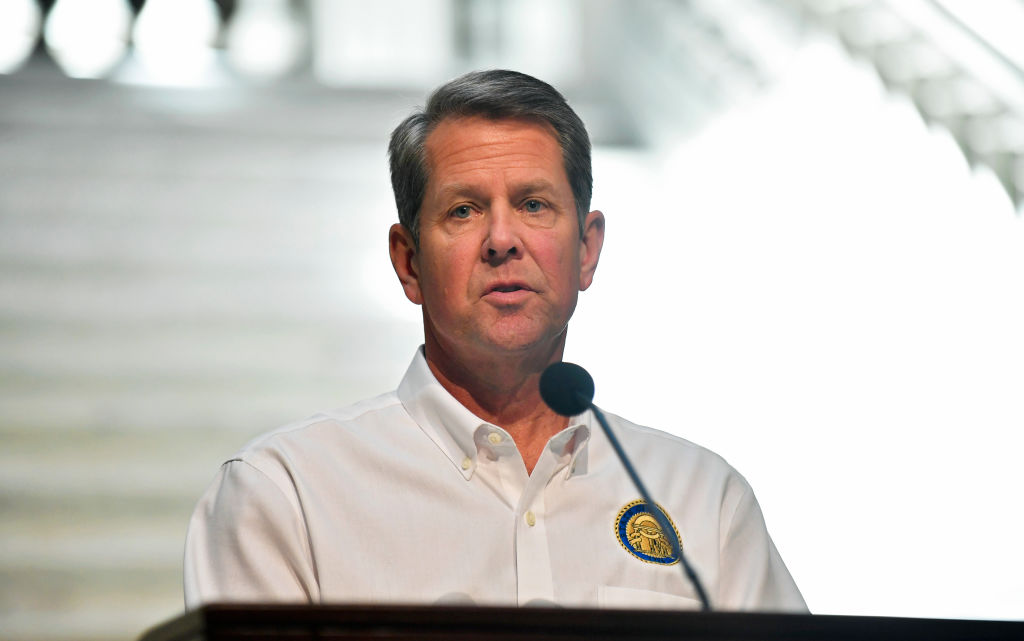

Georgia governor Brian Kemp approved a measure that adds legal protections for police officers Wednesday amid criticism from civil rights groups that say the new law is insulting to the Black Lives Matter movement and the fight for police accountability.

The approval comes weeks after Kemp signed a hate crimes bill into law; that measure had almost failed to gain the Legislature’s approval after Republicans added the police protections language into the same legislative package despite opposition from Democrats.

Adding the police protections language would have derailed bipartisan support for the hate crimes bill as lawmakers’ attempted to remove Georgia from the (short) list of states without a hate crimes law. Arkansas, South Carolina and Wyoming continue to lack an official hate crimes law (and advocacy groups continue to challenge the validity of Indiana’s law). As a result, Republicans took the police protection language out of the hate crimes bill and passed the measure supporting law enforcement, without Democrat support, in separate legislation.

The new police protection law adds an offense of “bias motivated intimidation,” described as when an individual intentionally intimidates, harasses or terrorizes “another person because of that person’s actual or perceived employment as a first responder,” which the bill outlines as a firefighter, police officer or paramedic.

This could include causing death or serious bodily harm, as well as damage to property valued at more than $500. The measure states that anyone who is convicted of committing a crime against a first responder because of their occupation would face between one to five years in prison, a fine of up to $5,000 or both. It also also allows “peace officers” to sue anyone for “filing a complaint against the officer which the person knew was false when it was filed.”

Critics say it overshadows the positive impact of the hate crimes law, which came into effect on July 1. “The hate crimes law is tainted [by a] compromise that puts Georgians in danger,” says Rev. James Woodall, state president of Georgia’s NAACP. If passing a police protection measure was the only way to establish a hate crimes law in Georgia, the state would have been better off without both of them, he adds.

Woodall worries that this provision allowing “peace officers” to sue over allegations determined to be false could deter people from filing valid complaints against the police for fear that they may not be believed—or that repercussions would follow. Georgia House Democrats said in a Twitter statement that it will have “a chilling effect on people.”

Gov. Kemp said in a statement emailed to TIME that the police protection measure was a “step forward to protect those who are risking their lives to protect us.”

“While some vilify, target, and attack our men and women in uniform for personal or political gain, this legislation is a clear reminder that Georgia is a state that unapologetically backs the blue,” he said.

But civil rights groups in the state swiftly weighed in with disapproval. Georgia’s NAACP said the police protection measure would “undoubtedly lead to violence against Black people” and was an “insulting compromise.”

The ACLU of Georgia’s executive director Andrea Young also expressed disappointment, noting that police already have many protections under Georgia law. The measure was “drafted as a direct swipe at Georgians’ participating in the Black Lives Matter protests who are asserting for their constitutional rights,” Young said.

The ACLU said in a previous statement that the new police protection measure “conflicts with existing Georgia law and creates uncertainty in how the law would actually be applied.”

Lauren Groh-Wargo, CEO of Fair Fight Action, suggested in a Twitter statement that the police protections measure was further proof that Kemp “does not care about Black lives.” It “may harm Black Georgians and protestors who become victim of corrupt police officers who already have sufficient protections in place,” Groh-Wargo said.

Georgia lawmakers finally voted on the otherwise stalled hate crimes measure, which had been stuck in a Senate committee for months, in the wake of the killings of Ahmaud Arbery and Rayshard Brooks. Their deaths reinforced national outrage over racism and police brutality.

“It is utterly reprehensible for us to equate the tragic losses of Ahmaud Arbery and so many other Black Georgians with a narrative that suggests that police are under attack,” Woodall says. Arbery’s mother Wanda Cooper-Jones previously said that the police protection measure “is more dangerous to our community than” the hate crimes measure “is good.”

Woodall was at Brooks’ funeral when he learned that both chambers of the Legislature had approved the police protection bill back in June. He remembers the event as “a room full of people who had the righteous indignation of a community that’s done dying.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com