In 1974, humorist Erma Bombeck published a syndicated newspaper column that looms over the lives of American mothers whether they’ve read it or not. In “When God Created Mothers,” Bombeck describes God making a mother with the help of an angel. “She has to be completely washable, but not plastic. Have 180 movable parts … all replaceable,” God tells the angel. “Run on black coffee and leftovers. Have a lap that disappears when she stands up. A kiss that can cure anything from a broken leg to a disappointed love affair. And six pairs of hands.”

My mother, who homeschooled eight children, saw that column as a mark of her valor. Not only did it hang on our wall at home, I grew up hearing it quoted in church sermons on Mother’s Day.

But once I became a mother, I came to hate that column. I think Erma Bombeck did us dirty.

As the pandemic forces us to rethink almost every aspect of our society, from why we go into an office to how we set up a kindergarten classroom, allow me to suggest that we reassess the very foundation of our society: motherhood.

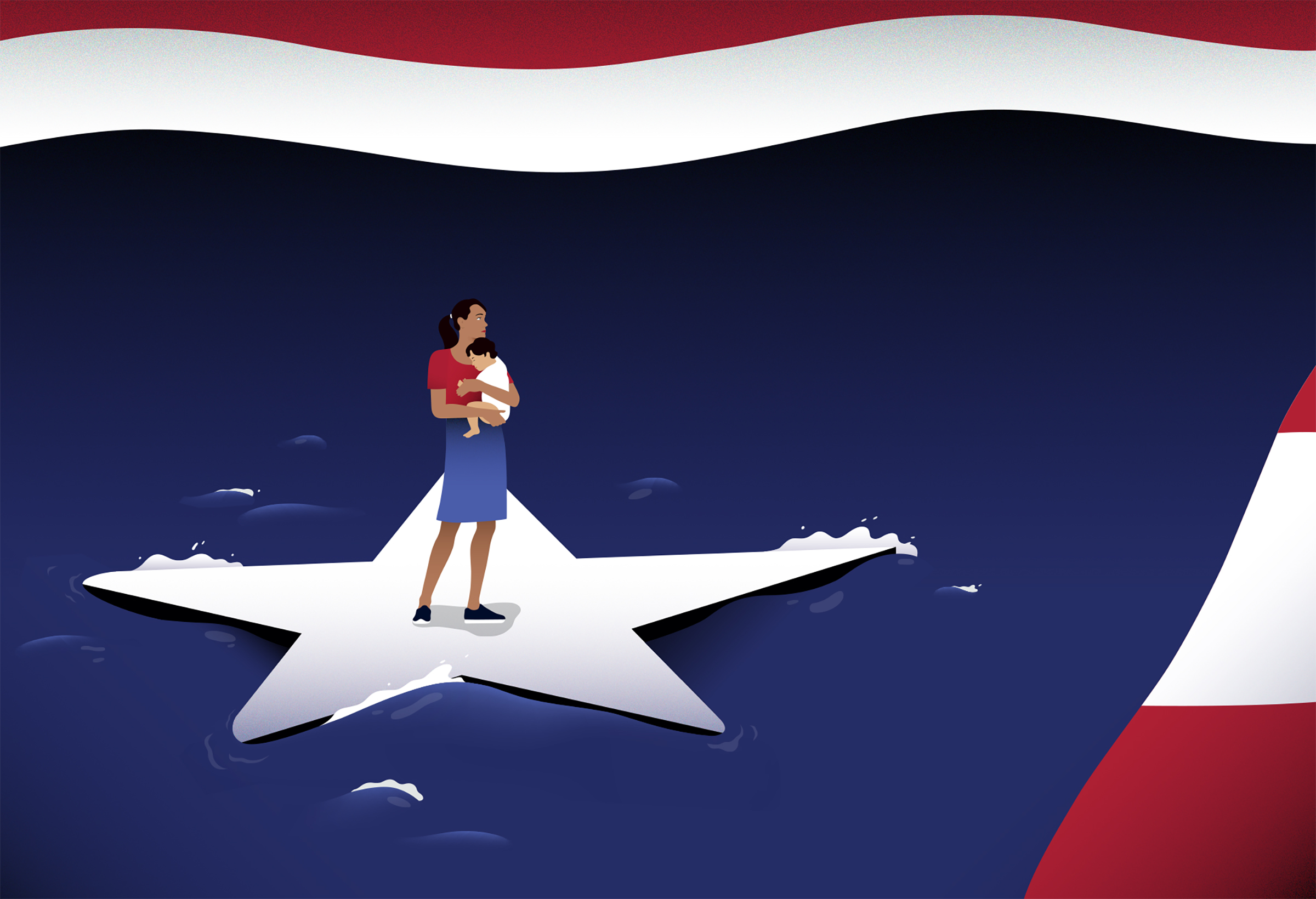

Motherhood is valorized in American culture because we don’t want to admit the truth: we have built an entire economy on the backs of unpaid and poorly paid women. Even as gender roles have shifted in the U.S., the expectation that the mother will be the parent primarily responsible for maintaining the household and taking care of the children, no matter what else she has on her plate, is still as true today as when Bombeck wrote her column. Never has this been clearer than during the pandemic.

Although in 2017, 41% of mothers were the sole or primary breadwinner for their family and an additional 23.2% brought home at least a quarter of their total household earnings, the loss of most outside support–from school, from camp, from day care–has meant that mothers are the ones picking up the slack. A recent study of about 60,000 U.S. households published in the academic journal Gender, Work & Organization showed that in heterosexual couples where both partners were employed, mothers “have reduced their work hours four to five times more than fathers.” There’s no reason to believe this will get better–and plenty of reasons to suspect it will get worse–as school districts announce back-to-school plans that are all remote or a hybrid of online and in person. The drive to reopen the economy without adequate childcare will force women from the workforce in record numbers.

Society will call it a choice, when in reality, it’s a failure of the system.

This is not a new problem, nor are the solutions a mystery. We’ve just chosen until now not to listen. It’s time to abolish our conception of what it means to be a mother in America and rebuild it on a policy level.

First, we need to normalize women receiving help with childcare. We are the only industrialized nation without guaranteed paid parental leave, and for half of Americans, full-time day care costs more than in-state college tuition. Additionally, other industrialized nations offer income supplements to help raise children or subsidies for childcare costs. We do not. This disregard has continued even in these unprecedented times. As economist Betsey Stevenson pointed out to Politico, “We gave less money to the entire childcare sector than we gave to one single airline, Delta.” The U.S. also ranks 26th in the world for access to preschool for 4-year-olds, and 24th for 3-year-olds. But access to early-childhood education rarely becomes a top policy priority. The implication is clear: Mom will take care of it.

We also need to recognize the hypocrisy in giving mothers so little support when we make it difficult for women to choose when and whether to have children in the first place. Recently the Supreme Court ruled 7 to 2 to allow employers the right to deny insurance coverage for birth control. In addition to preventing some women from getting pain relief from endometriosis and heavy periods, this decision takes away a measure of control that can alter the entire trajectory of a woman’s life. Meanwhile, states like Texas and Iowa, which had already put up barriers for women seeking abortions, tried to use the pandemic as a cover to further erode health care access for women by claiming the procedure was nonessential, a determination contradicted by leading health organizations.

America has the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world (a number that rises significantly for people of color), and in addition to taking steps to combat this disgraceful problem, we should actually take into account the considerable risk that comes with pregnancy and childbirth and the long-term implications for those who are forced to become moms when they’re not ready. A study by the research group ANSIRH (Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health) at the University of California, San Francisco’s Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health found that women who sought an abortion and were denied one were more likely to live below the federal poverty line, more likely to stay with abusive partners, and more likely to suffer life-threatening complications during pregnancy and birth.

Beyond letting women decide whether to have a baby, our government needs to pass legislation that would ensure that those who do become moms are paid the same as dads. According to the National Women’s Law Center, for every dollar white dads made in 2018, Asian American and Pacific Islander moms made 89¢, white moms made 69¢, Black moms made 50¢, Native moms made 47¢ and Latina moms made 45¢. In 2017, Michelle J. Budig, a professor of sociology at the University of Massachusetts, published a report, “The Fatherhood Bonus and the Motherhood Penalty,” in which she explained women’s wages tend to decrease after they have kids while men’s tend to increase, though these shifts are not equal across income distributions. “First, there is a wage penalty for motherhood of 4% per child that cannot be explained by human capital, family structure, family-friendly job characteristics, or differences among women that are stable over time,” she wrote. “Second, this motherhood penalty is larger among low-wage workers while the top 10% of female workers incur no motherhood wage penalty.”

Part of the disparity between fathers and mothers may be due to employer discrimination, Budig explained, citing research suggesting that companies view dads as more competent and worthy of promotion than moms. “Ideas of what make a ‘good mother,’ a ‘good father,’ and an ‘ideal worker’ matter,” she writes. “If mothers are supposed to focus on caring for children over career ambitions, they will be suspect on the job and even criticized if viewed as overly focusing on work.”

But modern motherhood is also relentless. Not only do mothers in America today continue to spend more time on both childcare and household chores than fathers do, despite men’s increased involvement at home, they also spend more time with their children than they did in the 1970s, when Bombeck wrote that mothers had to have six pairs of hands, even as they worked full-time jobs. Unable to justify the cost of childcare compared with their wages or, in the case of a global health crisis, faced with no childcare at all, women end up being the ones to walk away from work.

Previous economic crises in the U.S. have put men out of work, and we’ve bemoaned the hit to masculinity. This pandemic has hit women, specifically mothers, particularly hard, but instead of contemplating the creativity, discovery and productivity that are lost when women are forced from the workforce, we expect them to lean in so far, they fall off a cliff.

In the Bombeck column, the angel comments that the mother is too soft. “But tough!” God replies. “You can imagine what this mother can do or endure.”

How much longer will fables of valor be held up as an excuse for using mothers to prop up a failing system? Even if women can handle it, or at least appear outwardly to be handling it, does it really have to be this hard? How many fathers would find “enduring” to be a satisfying existence?

American mothers have been the undersupported cog in the wheel of American capitalism for too long. We must now completely reimagine their role and start over.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com