Denis Fortier, a retired education specialist from Lewiston, Me., has worked as a deputy election warden for several years. But both he and his wife Pauline, an election clerk, decided they weren’t comfortable working the Maine primary in July due to the coronavirus pandemic. Both are over 70.

“It was not an easy decision,” Fortier says. “It’s not an easy decision whichever way I go for the November elections. I’ve not made up my mind yet whether I’m going to work or not.”

Fortier fits the profile for a standard election worker: A retired, engaged citizen who comes back cycle after cycle to keep democracy running smoothly. According to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission’s (EAC) Election Administration and Voting Survey for the 2016 presidential election, 917,694 poll workers ran voting sites across the country. More than half the poll workers the commission gathered data from were 61 or older.

This year, many of those workers are considering sitting November out, leaving election officials scrambling to recruit replacements. “What we’ve heard from election officials is just a massive dropout of poll workers,” says Benjamin Hovland, commissioner of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. “That has real consequences. You can’t open polling places if you don’t have poll workers.”

The increase in mail ballots this year is expected to relieve some of the demand, but an adequate election-day workforce will still be needed to staff polling sites and count the ballots. In 2018, states used an average of eight poll workers per location, and nearly 70% of jurisdictions that responded to the EAC’s survey said they struggled to recruit workers.

The primaries have already demonstrated why it’s so important to plan ahead and ensure there are enough people to keep things running. Many states reported no-shows, resulting in long lines and even closed polling locations.

In Milwaukee, Wis., an expected 180 voting sites for the April 7 presidential primary were consolidated into five. The city typically requires at least 1,400 election workers, but had less than 400 as Election Day approached. The result was long wait times for voters. Due to the city’s large Black population, the delays disproportionately affected voters of color.

Shauntay Nelson, the Wisconsin state director for All Voting is Local, says the voting-rights group has been working with the City of Milwaukee municipal clerk and other local organizations to find “nontraditional” ways to recruit poll workers. Among their efforts are using social media, holding information sessions, and even hosting a job fair. She says they’re trying to recruit people from public-facing jobs, like bartenders, that may not be working on Election Day.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the daily D.C. Brief newsletter.

Efforts like this are underway in other states and on the national level. Ohio is offering lawyers Continuing Legal Education credit for taking part in the election. Iowa launched a recruitment campaign specifically requesting younger Iowans participate. Colorado offered election judges $3 more per hour and paid sick leave for the primary, while the West Virginia Real Estate Commission will allow agents and brokers to earn Continuing Education credit for their service. Many of the campaigns tap into patriotic themes. The Election Assistance Commission, Hovland says, also plans to announce soon that the agency will launch a poll-worker recruitment day for September 1, a new initiative spurred by the demand.

In Texas’ Bexar County, which encompasses San Antonio, several voting sites had to close during the state’s July 14 run-off elections because of a lack of poll workers. County Judge Nelson Wolff, who oversees guidelines and funding for elections on the local level as part of the Commissioners Court, says coronavirus concerns were to blame. Looking ahead to November, Wolff says the county is planning to create four “supersites” to reduce the need to staff so many places for early voting. While Bexar County typically has 280 voting sites for elections, Wolff says he anticipates cutting that figure to between 25 and 50 sites in November. “We’re taking a number of steps in anticipation that we will not be able to man all the polls on Election Day that we have done in the past,” Wolff says.

In South Windsor, Conn., poll workers will be paid an additional $100 in hazard pay for the presidential preference primaries on August 11, and may get the same bonus in November. The 26,000-person city would face a shortage of poll workers had younger poll workers not stepped in, according to Sue Larsen, the Democratic registrar. “The hazard pay was because we understood that this was a tough financial time and the fact that they were putting themselves in a situation that could be detrimental to their health,” Larsen says.

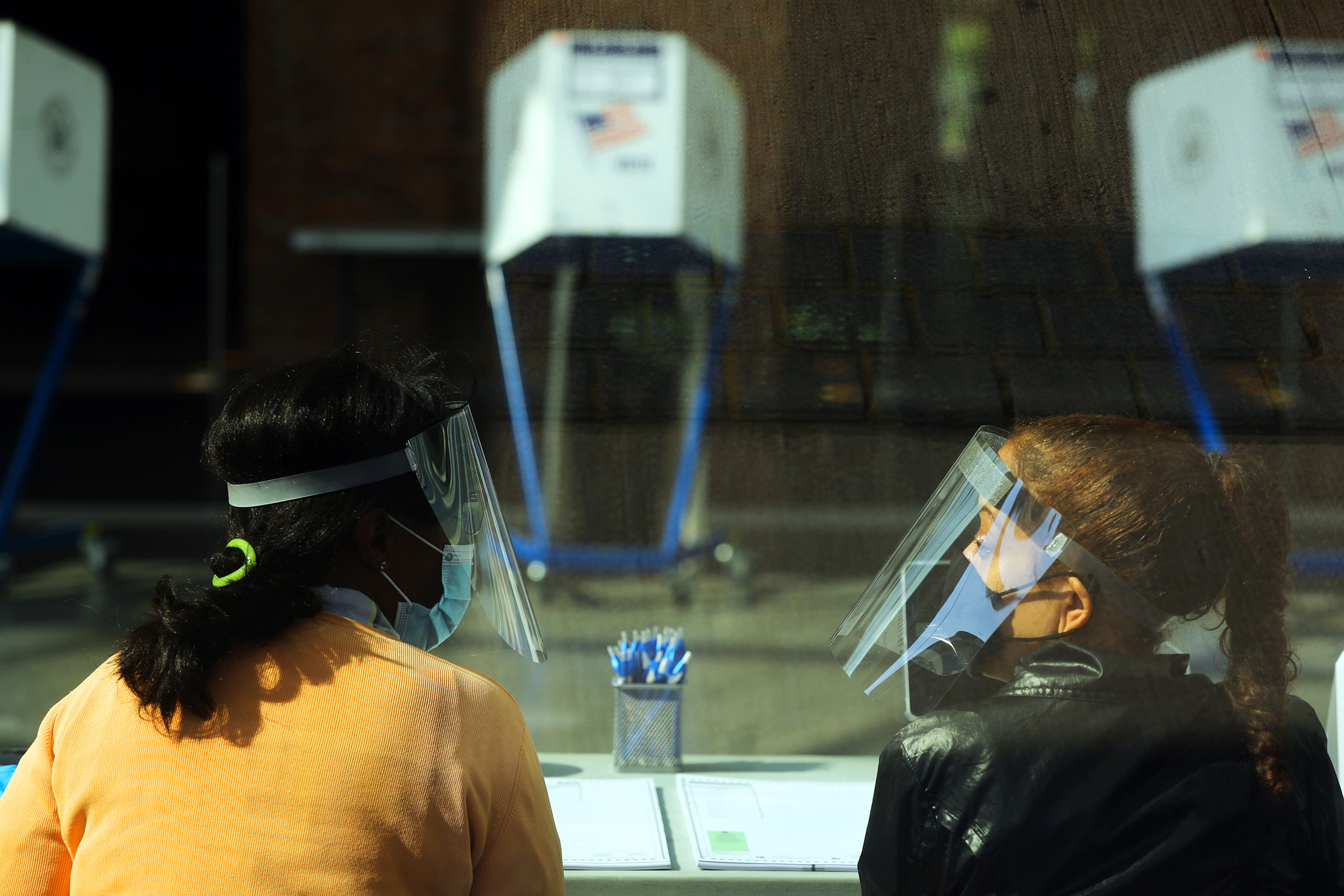

Poll workers are recruited and hired locally and help with tasks such as verifying voters’ identities, answering questions, and assisting voters who require it. Most of these roles are temporary and paid, requiring a short training period commitment and attendance on the day of the election. A majority of states even have youth poll workers programs, allowing minors to participate. Because so many of the workers build up a base of knowledge by returning election after election, training will be crucial this year because so many are likely to be first-time poll workers.

In Seminole County, Fla., Chris Anderson, the Republican Supervisor of Elections, said that because of the pandemic, the county had to build its bench of backup workers. While a lot of workers are returning, there will be a “very high degree of new folks,” Anderson says, estimating 30% of the poll workers for the August 18 primary election will be first-timers.

“What we do for all three elections, regardless of turnout, is we overstaff,” says Anderson. “We’re planners by nature, so we are always kind of looking at … the what-if scenario.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lissandra Villa at lissandra.villa@time.com