As long-simmering U.S.–China tensions come to the boil, a sweeping bilateral accord being negotiated between Beijing and Tehran is ringing alarms in Washington. It has the potential to dramatically deepen the relationship between America’s principal global rival and its long term antagonist in the Middle East, undermining White House attempts to isolate Iran on the world stage.

“Two ancient Asian cultures,” runs the opening line of a leaked 18-page Persian-language draft obtained by the New York Times earlier in July. “Two partners in the sectors of trade, economy, politics, culture and security with a similar outlook and many mutual bilateral and multilateral interests will consider one another strategic partners.”

The leaked document has come to light during a month that has seen tit-for-tat closures of a U.S. consulate in China and a Chinese consulate in the U.S.; meanwhile, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khameini renewed a vow to deal America a “reciprocal blow,” for the killing of Quds Forces Commander Qasem Soleimani in January and on July 27, satellite images showed that Iran had moved a dummy U.S. gunship into the Strait of Hormuz—apparently for target practice. But amid concern in Washington over a new China–Iran axis, there are several reasons to be skeptical of what the accord’s contents promise.

Here’s what to know about the state of China-Iran relations, what they portend for the future of the Middle East, and why the new accord might not live up to the hype:

What’s in the deal?

Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif confirmed on July 5 that Iran was negotiating a 25-year deal with China. According to the leaked draft, it paves the way for billions of dollars worth of Chinese investments in energy, transportation, banking, and cybersecurity in Iran. The draft also dangles the possibility of Chinese–Iranian co-operation on weapons development and intelligence sharing, and joint military drills, according to the Times, which also reports the deal could boost Chinese investments in Iran to $400 billion. But the accord has yet to be greenlit by Iran’s parliament or publicly unveiled, and the authenticity of the leaked Persian-language document has not been officially confirmed.

Public debate over the deal continues to rage in Iran, but comment from China has been scarce. When asked about it by a reporter on July 13, China’s foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said only: “China attaches importance to developing friendly cooperative relations with other countries. Iran is a friendly nation enjoying normal exchange and cooperation with China. I don’t have any information on your specific question [about the draft agreement].”

How did the deal come about?

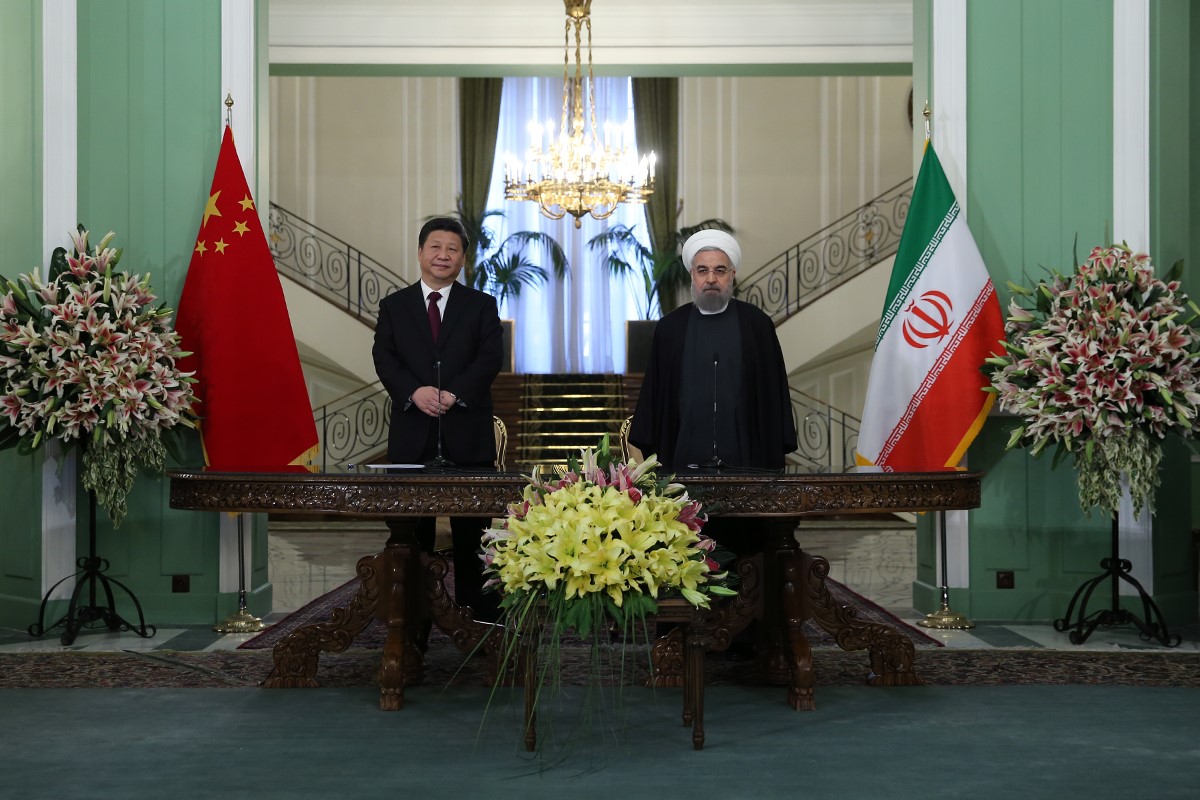

In January 2016, China’s President Xi Jinping visited Tehran to open a “new chapter” in relations between the two countries. That visit took place a year after the U.S. and other world powers concluded a deal to curb Iran’s nuclear program known as the JCPOA; and two before President Trump unilaterally pulled the U.S. out of the agreement. Cased in ceremonial language, the partnership China and Iran announced set out a goal of developing trade relations worth $600 billion —a fanciful figure even before the U.S. reinstated sanctions on Iran in 2018.

Yet trade with Iran has not been a priority for China in recent years and, for the most part, it has abided by U.S. sanctions. Beijing invested less than $27 billion in Iran from 2005 to 2019 according to the American Enterprise Institute, and annual investment has dropped every year since 2016. Last year, China invested just $1.54 billion in Iran—a paltry sum compared to the $3.72 billion it invested in the UAE or the $5.36 billion it invested in Saudi Arabia. Although China continued to purchase some Iranian oil after the U.S. imposed secondary sanctions, it did so at “what appears to be a token level” says economist Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, founder of a think tank that promotes trade between Europe and Iran.

China’s oil imports from Iran plummeted 89% year-on-year this March, as Beijing tried to secure a trade deal with the U.S. In June—officially, at least—China imported zero crude from Iran, compared to an all-time high from the Islamic Republic’s archrival Saudi Arabia.

Why does Iran want a deal with China now?

It needs the business. President Trump has waged a campaign of “maximum pressure” on Iran’s economy since 2018, threatening to sanction countries in Europe and elsewhere who buy oil and other exports from the Islamic Republic. He promised that this would help to “eliminate the threat of Iran’s ballistic missile program; to stop its terrorist activities worldwide; and to block its menacing activity across the Middle East.” American sanctions are yet to achieve these objectives but they have pushed Iran deep into recession.

Tehran sees a new accord with China as a way to extract more from a relationship that has so far entailed only “lukewarm” commitment, says Batmanghelidj. Yet even if trade between the two nations undergoes the sort of boost outlined in the leaked draft, “China cannot fully compensate for the shortfall in European trade.”

On top of the sanctions, low oil prices, the worst COVID-19 outbreak in the Middle East, the accidental downing of a Ukrainian airliner, and waves of protests have heaped further strain on Tehran. “The Rouhaini government needs to show something for its seven years in office,” says Ariane Tabatabai, author of No Conquest, No Defeat: Iran’s National Security Strategy. “People are exhausted and they just want to know that something good is going to happen at some point. This might be a way for the government to say: just hang in there, things will get better.”

What’s in it for China?

Discounted Iranian oil would provide a useful extra source of energy for China, which surpassed the U.S. as the world’s largest crude importer in 2017 and has long sought to diversify in its supply. Meanwhile, Iran’s geography opens an additional terrestrial route for Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—the sprawling global infrastructure development strategy adopted by the Chinese government in 2013. But Iran is neither a vital node for BRI nor a vital oil supplier for China. Beijing sees Iran as “a depressed asset” it can pick up at low cost, says Jon Alterman, Director of the Middle East Program at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). “China does not need Iran, but Iran is useful to China.”

Part of that usefulness comes from Tehran’s enmity with Washington, he adds. Rising tension between the U.S. and Iran potentially commits American military assets to the waters around the Persian Gulf, drawing resources away from the Western Pacific, where China seeks to establish naval dominance. Furthermore, disagreements over how to address Iran’s nuclear program drive a wedge between the U.S. and its allies—a boon for China, whose investment-centered foreign policy is based on bilateral partnerships rather than broader alliances.

By negotiating with Iran during a trade war, Beijing is signaling it is undaunted by the U.S. attempts to isolate Iran, and feels rising impunity over violating U.S. sanctions. But the vagueness of the deal leaves room to maneuver should Joe Biden win the American Presidential elections in November. A final draft of the Democratic Party’s platform advocates a “returning to mutual compliance” with the JCPOA.

How has the U.S. responded?

In a statement to the Times, the U.S. State Department warned that China would be “undermining its own stated goal of promoting stability and peace” by defying U.S. sanctions and doing business with Iran.

Experts say the potential deal shows the limits of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign. The policy was based on the idea that “Iran, and the world, had no good options but to comply with U.S. wishes” says Alterman. But for 40 years, Iran’s leadership has invested in an array of asymmetrical tools to escape foreign pressure, he says. The notion that Iran’s leaders would simply fold under U.S. pressure was always a “dangerous fantasy.”

Where else is China engaged in the Middle East?

Iran is one of China’s five principal partners in the Middle East—and the other four are all U.S. allies. Saudi Arabia is China’s largest trading partner in the region and foremost oil supplier; the UAE comes second in balance of trade and sees itself as a logistics hub in Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); and Egypt is important to China in part because of Chinese concern for transit through the Suez canal. Like Iran and the two Gulf states, Cairo is designated one of China’s “comprehensive strategic partners.” China also maintains close ties with Israel, with whom it co-operates on security and counterterrorism. Separately, Iraq is China’s third-largest oil supplier.

Beijing’s array of bilateral engagements in the region shows an investment-centric approach to foreign policy, rather than a Cold War-style network of alliances based on shared ideology. Key to that is making sure its strategy in one country doesn’t jeopardize its strategy in another. For U.S. allies like Israel, that means fears of a military China–Iran axis are overblown.

Beijing’s objective is “not to create a military alliance against the United States and certainly not against Saudi Arabia and Israel,” ran a recent editorial from Tel Aviv’s Institute for National Security Services. But it added that the risk of Iran threatening regional stability “should be emphasized by Israel to high-level Chinese parties.”

Saudi Arabia “is a far more important oil partner for China,” says Matt Ferchen, a China foreign policy expert at the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies, adding that Beijing’s diplomats are likely in close consultation with Riyadh over the terms of the deal.

Is China becoming a rival to the U.S. as the dominant global power in the Middle East?

With trillions of dollars spent on wars since 2001, more than 800,000 people killed, and unrelenting instability, America’s adventurism in the Middle East has come at an extraordinary cost. The U.S. desire to downsize its military presence in the region predates the Trump Administration and is expected to continue—in one form or another—no matter who wins November’s elections.

But that doesn’t mean China wants to fill the void. “If anything the Chinese are exploring what they can get without replicating what the U.S. did,” says CSIS’s Alterman. That exploration involves developing a series of bespoke commercial relationships that are not backed by conventional military force.

In an October 2019 survey of policymakers on Iran, Chinese respondents told London-based think tank Chatham House that Beijing’s interests in Iran are predominantly economic, and take priority over security and geopolitical interests. Investment that comes without demands for neoliberal economic reforms is an attractive option for ailing regimes.

Others are taking notice. Last month, as Lebanon negotiated with the IMF amid its crippling economic and political crisis, Hezbollah leader Hasan Nasrullah urged Beirut to “look east” for support. And last year, months before resigning in the face of bloodily repressed protests, Iraq’s former Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi promised that Baghdad–Beijing relations would undergo a “quantum leap.”

How has the Iranian public responded?

Vociferously, against the deal. Although the terms of the deal have not been publicly unveiled, critics have already likened it to the humiliating Treaty of Turkmenchay, which Persia signed with Russia in 1828. On social media, Iranians claimed the accord entails Iran giving up land to China, or allowing China to stage its troops in the country.

Those rumors are unsubstantiated, but the public skepticism is not. Iran has in the past turned to China to relieve economic pressure but “China has never been able to deliver, or willing to deliver for that matter,” says Tabatabai. Zoomed out, the leaked draft may appear comprehensive, but there are scant specifics on what individual projects will involve. “It’s more like a roadmap. There are a lot of promises and very broad contours for what future negotiations might entail,” she tells TIME, “but I don’t think it is going to do what the government hopes it will achieve.”

With reporting by Charlie Campbell / Shanghai

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Joseph Hincks at joseph.hincks@time.com