It was the Chinese philosopher Sun Tzu, and not Al Pacino in The Godfather Part 2, who first said, “Keep your friends close, and your enemies closer.” Yin Weidong, the CEO of Chinese biotech firm SinoVac, seems to have taken that advice to heart.

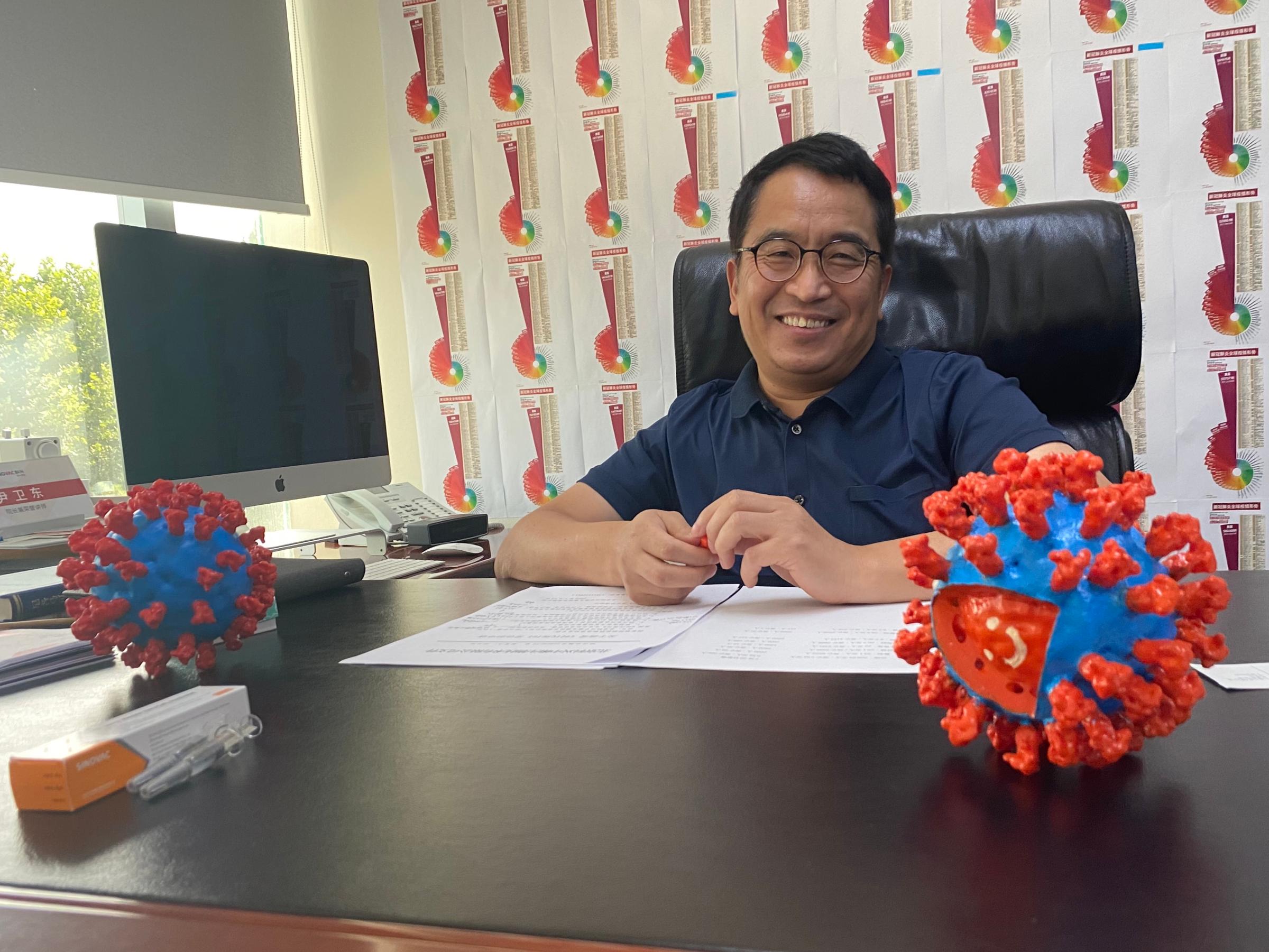

On the desk in his office in Beijing are two plastic models of a virus—each blue core surrounded by red protein spikes. From the time it started spreading in the central Chinese city of Wuhan in late December, containing that virus has occupied virtually every waking moment for the scientist.

The pandemic we now know as COVID-19 is rampaging across every continent. On the dozens of daily infection charts, broken down by nation and pasted floor to ceiling on Yin’s office wall, the numbers tell a horrifying story: 16 million infections and 640,000 deaths worldwide, including 146,000 American lives lost as of Monday.

But if the enemy is close, so is a possible new friend. Yin’s desk is now also home to several small glass vials of SinoVac’s COVID-19 vaccine—dubbed CoronaVac—that began phase 3 trials involving 9,000 volunteers in Brazil last week. (A phase 1 trial involves small groups of patients to check a vaccine for negative side effects, and a phase two trial usually tests for a combination of safety and efficacy, while a phase 3 trial is like a phase 2 but involving many more participants.)

“Looking at the data collected, I think we have more than an 80% chance of success,” says Yin.

Normally, getting from pathogen identification through phase 3 trials in about 10 years is considered quick. The mumps vaccine is generally considered the fastest ever developed at four years. But if all goes well, CoronaVac might be ready for regulatory approval early next year. Not that Yin is satisfied.

“Do you really think this is fast? Compared with the spread of the virus, it’s not fast enough,” he says, holding his plastic nemesis aloft with grudging respect. “That is how we should measure our progress.”

During the 2002 to 2003 SARS outbreak, which claimed over 774 lives worldwide, SinoVac was the only firm to go into phase 1 vaccine trials, but the pandemic suddenly disappeared. That meant that research was discontinued at a huge loss for the firm. It wasn’t entirely wasted, however. Now, 17 years later, SinoVac is able to build on that earlier work, given that COVID-19 is very similar to SARS. It and coronavirus are “like brothers,” says Yin.

Still, creating an effective vaccine is just a third of the battle. The other two prongs of vaccine development are production capacity and getting regulatory approval. At present, every nation’s FDA equivalent would need to approve CoronaVac independently, though given the unprecedented need, there are conversations about streamlining.

“The virus doesn’t require a passport but the vaccine needs to be licensed by every country,” says Yin.

SinoVac is aiming to triple current capacity to produce 300 million doses per year. That might sound impressive, but accessibility is likely to be a big issue. Given that at least two doses will be required to immunize one person, it would still take almost a decade to vaccinate every person in China alone, never mind sharing the vaccine with the world’s 7.6 billion people.

“If only one or two countries get protected this won’t solve the problem and get economic activity back to normal” Yin says.

SinoVac isn’t the only company with a potential vaccine in clinical evaluation. There are over 20 companies around the world engaged in the task with more than 130 vaccines in development, according to the WHO. But given the scale of the need, there’s going to be no quick fix to the pandemic.

Another vaccine candidate, developed by U.S. biotech firm Moderna with the National Institutes of Health, provoked the desired immune response in a test of 45 individuals, and is about to enter phase 3 trials. It functions by introducing an mRNA sequence—a molecule that tells cells what to build—coded for a disease-specific antigen. Once produced within the body, the antigen is logged by the immune system, empowering it to fight the real virus.

But while such RNA vaccines, as they’re known, have multiple benefits—including speed of production—they must be stored at sub-zero temperatures. That means their distribution to far-flung populations is problematic. While SinoVac initially experimented with RNA and other vaccine prototypes, they found that a traditional inactivated virus vaccine produced the best results. Under normal conditions, Yin believes CoronaVac has a shelf life of three years.

“The purpose of this work is not to discover which technology is better,” says Yin. “The purpose is to control the disease.”

In principle, SinoVac is a private company that owns CoronaVac as its licensed intellectual property, meaning where the vaccine is distributed should be a purely commercial decision. However, the Chinese government has contributed to the estimated one billion renminbi (about $140 million) the firm is investing in CoronaVac. This and other contributions from international NGOs currently under negotiation all come with distribution commitments attached.

In a speech to the World Health Assembly on May 18, Chinese President Xi Jinping promised to make a COVID-19 vaccine produced in China a “global public good.” In reality, of course, every queue has someone at the back, meaning there will be much jostling for priority—and potentially boosting Beijing’s global clout.

According to Benjamin N. Gedan, a former regional director on the White House’s National Security Council now with the Wilson Center, “If China produces the first coronavirus vaccine at scale, it would be an extraordinary diplomatic tool anywhere in the world.”

SinoVac has already committed to sharing 60-100 million doses in Brazil through a collaboration with São Paulo-based Instituto Butantan, which is performing the phase 3 study. In Asia, the firm is “actively in discussion with several countries,” says Yin, including Indonesia and Turkey, and is exploring options in Europe. It has also had more than 30 meetings with the WHO to update the global health body on its progress.

“We will share our vaccine with the world,” says Yin.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlie Campbell / Beijing at charlie.campbell@time.com