In January 1918, as the people of Porvenir, Texas, slept, a group of Texas Rangers, U.S. Army cavalry soldiers and Anglo ranchers invaded the town. They abducted 15 Mexican men and boys, took them to a nearby hill overlooking a river and shot them from 3 ft. away, killing all of them. The rest of the villagers sought refuge in Mexico. Days later, the executioners burned what was left of the town. They claimed, without proof, that their victims had been connected to a recent raid at the nearby Brite Ranch.

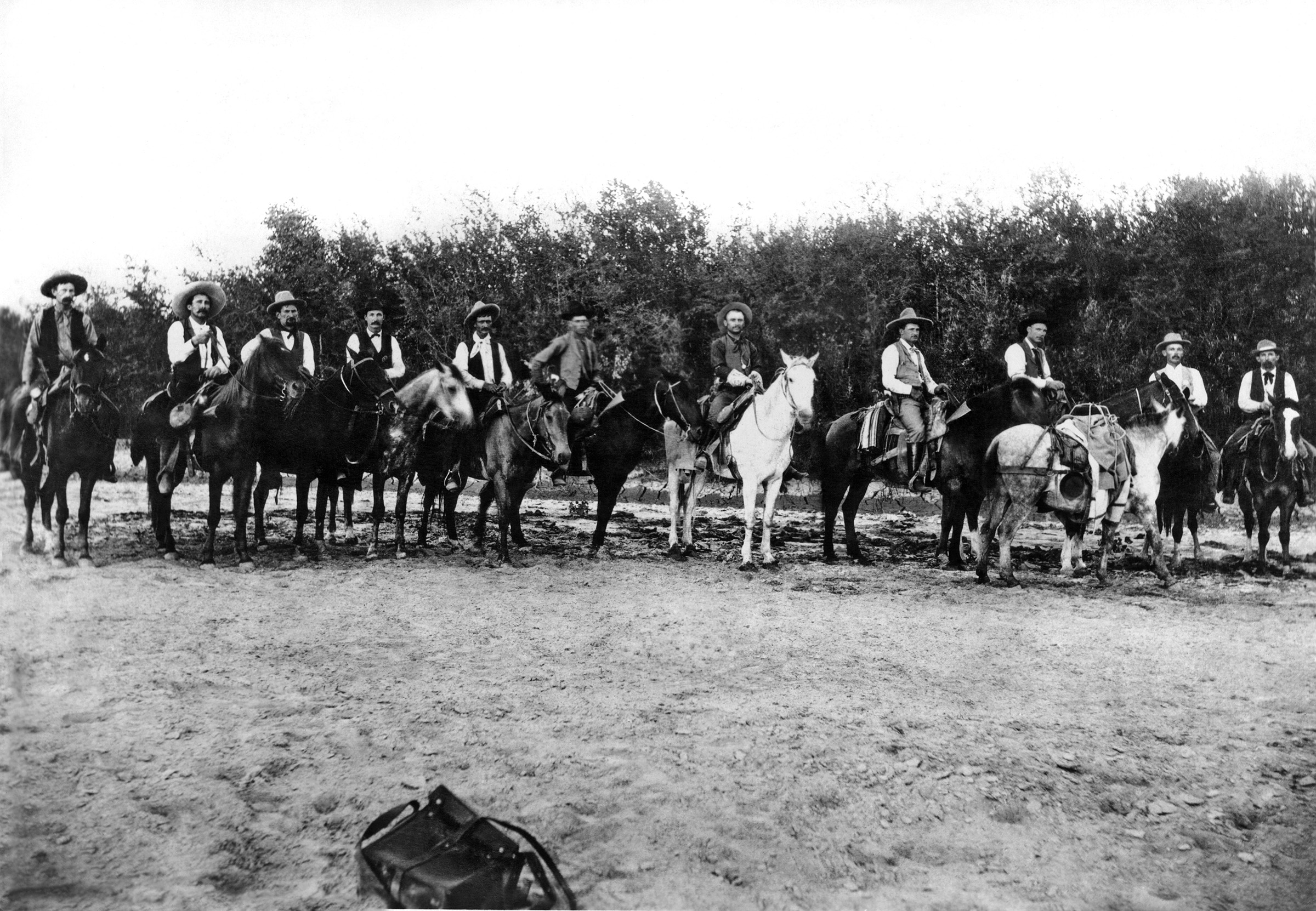

The rotten law-enforcement system we have today is the rapacious fruit of institutions like the Texas Rangers that were sowed specifically to persecute Black and brown bodies. From the early days of this country, law-enforcement officers have conducted themselves with little consequence for their actions because the government has never placed much value on the lives of people of color. While the origins of police in America vary, we know in the South they had their roots in slave patrols targeting African Americans. The Texas Rangers, created in the 1820s, are often seen as American heroes, almost mythical in stature. But they were a racist, repressive and violent force that rained terror on Mexicans and Native people as they cleared the way for westward expansion.

“They burned peasant villages and slaughtered innocents. They committed war crimes. Their murders of Mexicans and Mexican Americans made them as feared on the border as the Ku Klux Klan in the Deep South,” notes Doug J. Swanson in his new book Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers. From 1915 to 1920, up to 5,000 Mexicans “innocent of any crime but the one of being Mexican” were killed by the Texas Rangers, write Julian Samora, Joe Bernal and Albert Peña in Gunpowder Justice: A Reassessment of the Texas Rangers. The specific agencies may have changed over the years, but racist attitudes and actions in law enforcement have persisted. (The Texas Rangers today are a division of the state’s Department of Public Safety, but perhaps it’s not surprising that some former Rangers joined Border Patrol when it was formed in the 1920s.)

The history of state-sanctioned police violence against Latinos has been largely erased, with many of the stories buried in forgotten graves. Community organizers like those of Youth Justice Coalition L.A. and Unión del Barrio have been working tirelessly to bring justice to families of Latinos killed by police and to raise awareness of the ravages of law enforcement on our people. Youth Justice Coalition L.A. has also fought to abolish the presence of cops in schools—in Los Angeles Unified School District, 73.4% of the student population is Latino. This work rarely makes national headlines. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD) has for decades faced allegations that it is home to “deputy gangs” of white officers who work in primarily Black and Latino neighborhoods. In 1991, a federal judge described one such group as “a neo-Nazi, white-supremacist gang” and said higher-ups in the department “tacitly authorize deputies’ unconstitutional behavior.” Without understanding the deep structural forces behind the violence waged against us, it’s easy to dismiss the deaths of Latinos at the hands of police as few and far between.

On June 18, Andrés Guardado, an 18-year-old Salvadoran American, was shot and killed by a Los Angeles sheriff’s deputy. At the time of his death, he had been working as a security guard at an auto-body shop. His father, Cristóbal Guardado, told me Andrés was working two jobs to pay for his car and to help the family stay afloat after they took a financial hit due to COVID-19. The officers allege Guardado had a gun, but his family has repeatedly disputed the account. The sheriff’s office placed a “security hold” on Guardado’s autopsy, further rupturing trust with the community it is supposed to serve, but on July 10, the L.A. County coroner released the official autopsy results defying orders from LASD. The report showed that Guardado was shot five times in the back and had two other graze wounds. “The manner of death is homicide,” it said. As of July 8, the deputy who killed Guardado was still employed by LASD and had not been interviewed by investigators. “We’re on his timetable,” commander Chris Marks said at a press conference.

Guardado was not the only young Latino killed by police in California that month. On June 2, Sean Monterrosa, 22, was killed by a detective who shot five times through the windshield of an unmarked police vehicle. Vallejo police chief Shawny Williams initially said Monterrosa was on his knees with his hands above his waist when he was killed and that the detective who shot him thought he saw a gun, but it turned out to be a hammer. Then later that day, the department issued a statement that made Monterrosa seem more threatening, saying he “abruptly turned toward the officers, crouching down in a half-kneeling position as if in preparation to shoot.” On June 6, California Highway Patrol officers in Oakland shot Erik Salgado, 23, and his pregnant girlfriend in what his family’s lawyer called “a massacre.” Police said he was “ramming” the car he was driving into their vehicles, but his family’s lawyer says he was shot multiple times first. Salgado died; his girlfriend survived, but lost the baby.

As of June 9, according to a database compiled by the Los Angeles Times, 465 Latinos had been killed by police since 2000 in L.A. County alone. Nationally, 910 Hispanics have been killed since 2015. It’s worth noting that Latinos are often undercounted in criminal-justice data since many states report race but not ethnicity.

In 2013, Andy Lopez, 13, was killed by Sonoma County sheriff’s deputy Erick Gelhaus. Lopez was walking through a vacant lot when the officer mistook his toy gun for an AK-47. Gelhaus shot Lopez seven times, killing him at the scene. No criminal charges were filed. In 2014, Alex Nieto, 28, was eating a burrito and chips at a San Francisco park when a passerby deemed him suspicious and urged his partner to call 911. One officer unloaded his entire clip, then reloaded, shooting 23 rounds total at Nieto. Another officer shot 20 times. Two more officers drew their guns and shot at least five times while Nieto lay on the ground dying. They were not criminally charged. In a civil case against them, they claimed they thought the Taser he was carrying was a gun, and a jury found that they did not use excessive force.

The names of Latinos killed by police go on and on, as is painfully clear at Black Lives Matter protests. On June 24, at the weekly Black Lives Matter L.A. protest to remove District Attorney Jackie Lacey, families of those killed by police spoke the names of their loved ones. Many of them were Latino, including Afro-Latinos. Thanks to the Black community’s arduous work to increase police accountability and awareness, and its bold vision for defunding the police and imagining a system that serves the people, the vicious killings of Latinos are starting to gain national attention. This is the manifestation of “when Black lives matter, then all lives will matter.”

We can no longer be averse to the history and truth. The descendants of the victims of Porvenir, Texas, sought to memorialize the massacre with a historical marker but were initially met with resistance from the chair of the Presidio County Historical Commission, who wrote in an email to the Texas Historical Commission that, “militant Hispanics have turned this marker request into a political rally and want reparations from the federal government for a 100-year-old plus tragic event.” Jim White III, a descendent of the Brite family, told the New York Times that it was a “turbulent time on the border when you had a lot of people getting killed on both sides.” When it comes to crimes committed against people of color, two sides always magically emerge. After the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017, in which neo-Nazis clashed with protesters fighting for social justice, President Trump said there were “very fine people on both sides.”

The relatives of those killed in the Porvenir massacre did finally get their marker in 2018. The 910 Hispanics who have been killed at the hands of police since 2015, and in the years before these databases existed, deserve our attention, activism and remembrance too. We cannot wait another hundred years before we tell their stories.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com