The fall semester has yet to begin, but student athletes training for the season can already be found on college campuses across the U.S. And so can COVID-19.

Since the start of July there have been at least two outbreaks among student athletes, coaches, and staff—with 37 infected at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Chapel Hill and 22 at Boise State. Clusters of infection have been traced to college town bars popular with students.

A common misconception is that young people with COVID-19 don’t die and therefore college re-openings pose little risk. Sadly, this isn’t the case. COVID-19 deaths in the young are rare, but they happen. Universities across the U.S. are mourning the loss of students in the lead-up to the school year, including Joshua Bush, a 30-year old nursing student at the University of South Carolina, Trevor Syphus Lee, a 27-year old senior at Utah Valley University, and Juan Garcia, a 21-year old Penn State undergraduate.

One might imagine that the rapid, uncontained spread of a serious and poorly understood disease which is already killing students would cause universities all across America to put their re-opening plans on hold. Unfortunately, that’s not the case.

The Chronicle of Higher Education compiled a database of the fall reopening plans of over 1,000 colleges and universities and found that 60% are “going to open for business and bring all of their students back.” Given how much is still unknown about the virus and especially its long-term effects on those infected, this could be the largest-scale uncontrolled public health experiment America has ever undertaken, with students, staff, faculty, parents, and communities as the unwitting test subjects. No other nation has reopened schools and universities with the level of rampant community transmission we see in the U.S. today, or with so little coordination or guidance as to protective measures.

The rush to re-open is driven by the very reasonable conviction that universities and colleges ought to provide their students face-to-face classroom teaching and a residential “campus experience.” There is more to college than the transmission of knowledge, and online learning has significant disadvantages. But during a pandemic, both classrooms and presumably campus residential settings present risks universities are not equipped to handle.

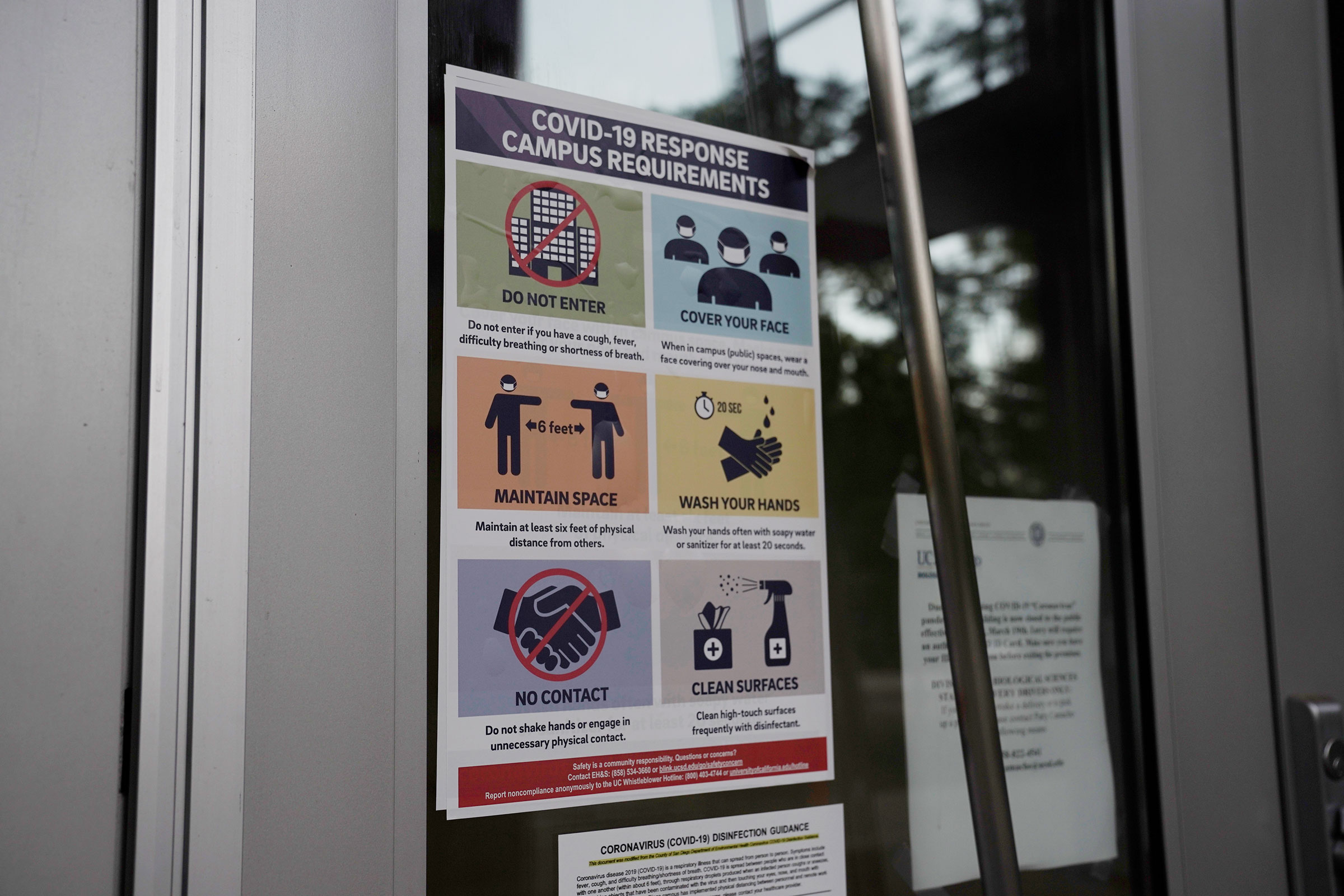

Safety measures proposed so far revolve around sanitation, masks, and physical distancing. These might be sufficient for a trip to the supermarket; for several reasons, they are likely to fail in the context of daily life at a university.

First, some colleges are only “encouraging” (not mandating) mask wearing this fall, drastically reducing effectiveness. When a strict rule is in place, classroom enforcement will likely be up to individual instructors, and proper mask use (e.g., a snug fit that keeps all noses covered) cannot be guaranteed.

Second, physical distancing is a moving target. Some states have argued that 4 feet of distancing is enough in the classroom, on the assumption that everyone will only cough (or breathe) straight ahead. UNC Chapel Hill even suggested that 3 feet would do, until an outcry caused them to reverse course.

Third, evidence suggests that when students and instructors spend extended time together in the classroom, even universal mask use and six feet of distancing may not be enough.

There is a growing consensus that in places with an uncontrolled COVID-19 epidemic, being inside a building where people are talking—such as in a bar, restaurant, office, or classroom—puts you at risk of infection. We now know that SARS-Cov-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, can linger in the air in the form of tiny droplets (aerosols) and can infect people as they breathe in.

Research has shown that air flow can transmit aerosolized SARS-Cov-2 much further than 6 feet. In the absence of constant and efficient ventilation, viral particles can remain airborne for at least 3 hours. In most universities, opening all the windows and doors would be impractical or impossible, and air conditioning systems can waft recycled air over occupants for hours. Masks help, but they’re not perfect protection.

Not surprisingly, many professors, particularly those who are older or have pre-existing medical conditions, say they will refuse to teach inside classrooms. But to be able to refuse, you need some degree of power. There’s a real risk that so-called contingent faculty, those in “insecure, unsupported positions with little job security and few protections for academic freedom” will have no choice—they will feel pressured to teach in person or be replaced.

Beyond the classroom, colleges and universities are “congregate settings” that are known to create high risk for viral transmission, akin to nursing homes or cruise ships. The campus experience includes bringing students together in dormitories, dining halls, athletic training, parties, bars and clubs—gatherings that would risk becoming “superspreading events.”

Some universities are hoping that a pre-semester quarantine period, an honor code that encourages students to self-report symptoms and adopt masks and distancing, and campus-wide contact tracing will help avert catastrophe. But a recent study led by Dr Sherry Pagoto at the University of Connecticut—a survey of 2,698 students who will be returning to campus in a few weeks, and in-depth interviews with a further 35 students—suggests that many obstacles lie ahead, especially if students are not meaningfully engaged in the reopening planning process. (Dr Pagoto has shared the initial findings of the 35 in-depth interviews on social media.)

Every student said quarantine is not realistic and will fail. They also said that if they develop mild COVID-19 symptoms, they may not report them. If they become infected, they’d be reluctant to tell the university about their contacts, especially those at bars. They were pessimistic about the safety of social events, suggesting mask use would not be universal. The fact that 117 students at University of Washington fraternities have tested positive since late June suggests that such fears are well founded. The overarching message seems to be that just telling students not to do things and leaving it at that is not a reliable policy.

While the risk of death from COVID-19 is lower among the young than the old, we’ve seen that young adults can die of the disease and the risk is five to nine times higher among those who are Black, Latinx or Indigenous. Even if they recover from the initial acute illness, infection with the novel coronavirus can have debilitating long-term consequences, including lung disease, heart problems, brain damage, and mental health problems. And we don’t yet know what other lingering effects the disease might have.

Infections among students will also put the lives of others around them at risk. The highest risk of death will be among service and maintenance staff on campus—cleaners, bus drivers, food service employees, janitors, facilities managers and support staff—who wield little institutional power. A recent outbreak of COVID-19 among housekeepers at UNC Chapel Hill, tasked with cleaning the rooms of student athletes, is just the tip of the iceberg. Over 40% of service and maintenance staff on U.S. university campuses are people of color, who are at elevated risk of dying if they become infected with SARS-Cov-2.

For the city where a campus is based, reopening will be like dropping a cruise ship into the center of town—and giving passengers free rein. Campus outbreaks cannot be hermetically sealed—they will inevitably cause a spike in community spread, affecting the city, state, and beyond. Universities that fully re-open in the midst of an uncontrolled epidemic will bear responsibility for the damage they cause to their wider communities.

What would it take to re-open safely? We can look to Taiwan as an example. Rather than leaving individual universities to piece together their own plans, Taiwan’s Ministry of Education produced a national strategy for college campuses. The strategy included an initial quarantine, frequent testing of all students, sanitation, masks, distancing, reduction of student density, cleaning of dorms twice daily with bleach, and allowing only one student per dining table. It also included mandatory quarantine for anyone exposed, and infection-number thresholds at which an entire university would shut down. With this huge array of protective measures on campus, Taiwanese universities were able to reopen successfully and see a total of just seven confirmed university-based cases by June 18, and only four new cases nationwide since then.

Aside from the safety protocols more rigorous than any we’ve seen proposed in the U.S., Taiwan’s universities had another advantage America’s don’t: a well-controlled epidemic with virtually no community transmission. To date, Taiwan has had only 451 cases and seven deaths. Not a single state in the U.S. has had anything like that level of success.

In that context, it’s hard to see how any U.S. university could have a safe on-campus reopening plan comprehensive enough to succeed.

We understand the financial pressures that colleges and universities are facing. Some could risk bankruptcy without the revenue that reopening will generate. We also recognize the enormous benefits of campus life and in-person teaching and the wishes of some students and parents to experience these. But at what price?

These institutions need to be honest about the trade-offs. They should publish their estimates of the number of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths that re-opening will cause. That will allow students, instructors, parents, and the wider community to better understand how much suffering must be endured, and by whom, as the price for the benefits of reopening. These institutions should also state clearly what level of illness will trigger another shutdown.

The Trump administration is applying increasing pressure on the education system to reopen, hoping that Americans will grow numb to COVID-19 deaths. Colleges and universities should not become complicit in fostering numbness, even if suspending in-person tuition would threaten their financial viability. They should put the health and safety of their students, instructors, service and maintenance staff, and communities first. Who else do they exist to serve?

Clarification, July 20: The original version of this article didn’t specify the extent of Dr. Pagoto’s findings she has shared online.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com