When Christine Baker, a financially strapped stay-at-home mom to two little girls, made up her mind to lose 30 lb., she took a cue from a friend who’d gotten fit with Beachbody. The company’s online workouts and diet products cost Baker about $160, but they worked.

“Literally within 30 days, I looked and felt like a different person,” says Baker, of Roseville, Calif., who was so impressed with her 2015 transformation that she decided to become a Beachbody fitness coach herself. She started paying around $135 per month to set up her own online portal and to purchase Beachbody products, and she got to work looking for customers. Yet as she spent more hours trying to sell people on Beachbody and fewer hours working out herself, Baker says the pounds piled back on but the money did not roll in.

“You’re working your ass off. You’re having to check in every day in your group, you’re having to keep everybody motivated, because if they don’t lose weight and see results, they’re not going to keep buying from you,” says Baker, 48. “It was like I was just throwing money away.” By the time she gave up on Beachbody, Baker says, she’d lost several thousand dollars and countless hours that she wishes had been spent with her daughters.

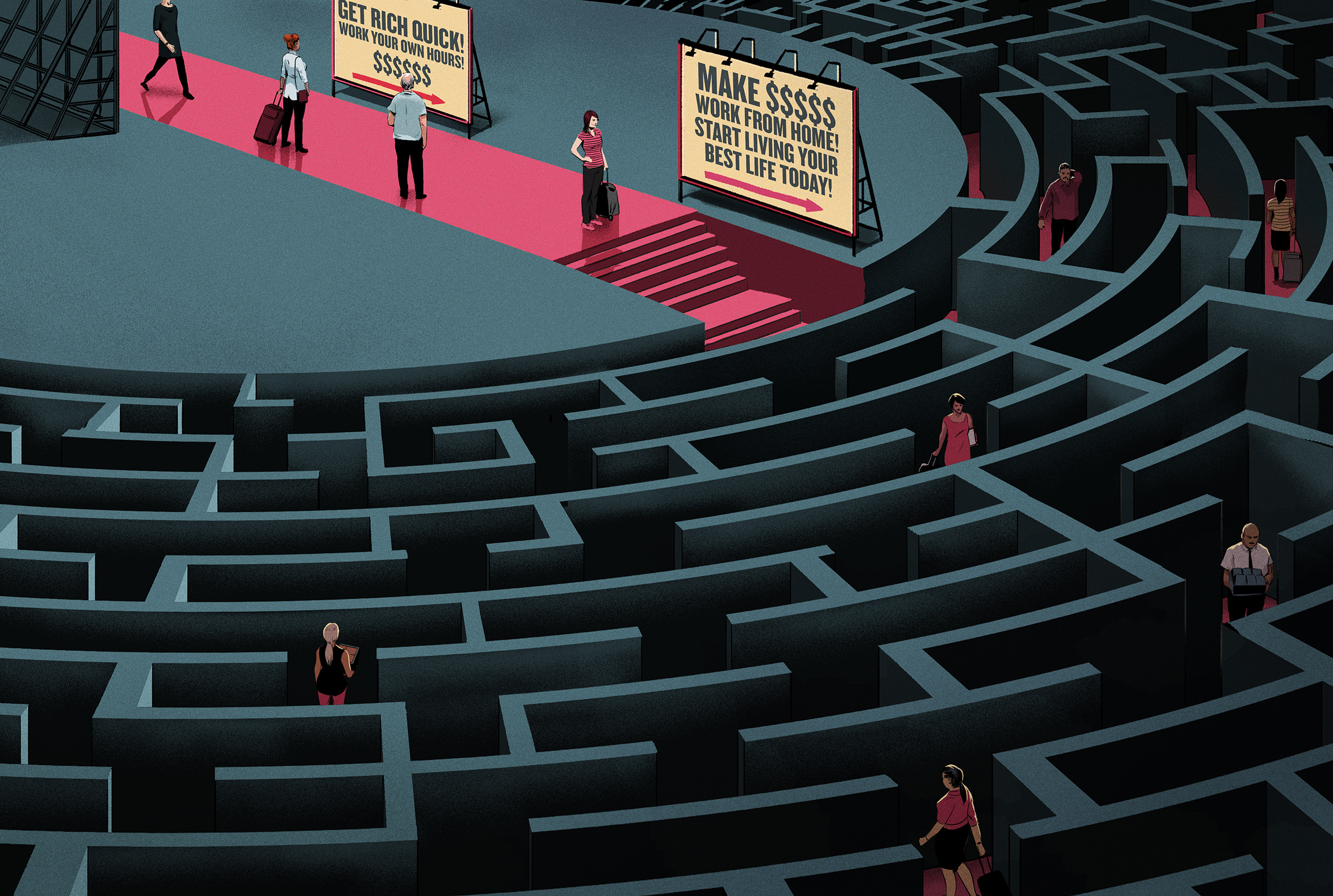

Multilevel marketing companies (MLMs) like Beachbody, which rely primarily on distributors like Baker instead of salaried staff to sell goods and services, have long been eyed with suspicion by regulators, and for good reason. The Consumer Awareness Institute, whose research has been posted on the website of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), found that 99% of people who participate in them lose money. “Statistically, it is more likely you will win the lottery than you will make hundreds of thousands of dollars selling for an MLM,” says Robert FitzPatrick, the co-author of False Profits, a book about MLMs, and the president of PyramidSchemeAlert.org.

But as the COVID-19 pandemic sends the economy into its worst tailspin since the Great Depression, some MLM distributors are wooing new investors with promises of big money and the opportunity to work from home–seemingly ideal for people who are unemployed. Facebook posts promising jobs are easy to spot, though the caveats that these opportunities do not offer guaranteed paychecks are rarely mentioned. “Worried about the Coronavirus?” reads a Facebook post by a Young Living essential-oils distributor touting its Thieves product line. “Thieves kills germs!” A similar post by a seller for Color Street, an MLM that sells nail-polish strips, urged members to “invest some of that stimulus check in yourself and start making money instantly.”

Some sellers imply that their non-FDA-approved supplements and essential oils can protect people from the virus. “With the flu and coronavirus spreading throughout the U.S., things are selling out,” wrote a seller for doTERRA, an essential-oils MLM. “If you are running low on these immune boosting protection items, now is a good time to replenish.” TIME reviewed dozens of similar claims made on social media.

The FTC has sent letters to 16 MLMs warning them against making claims about the coronavirus-related health benefits of their products, the potential earnings for investors, or both.

But the FTC is fighting an uphill battle as the $35.2 billion industry rapidly evolves, courtesy of the Internet. Unlike MLMs of yesteryear that relied on door-to-door sales, today’s MLM distributors can reach millions of potential recruits around the world on Facebook, Instagram and other social networks. Included in a distributor’s marketing tool belt are private messages, which regulatory agencies like the FTC can’t monitor. “[Social media] can be like a laboratory for deception,” says Kati Daffan, the FTC’s assistant director for marketing practices. “You’ve got all these members competing with each other to deceive more people. And they can do it however they want if there’s no one watching from above.”

And with so many people out of work, there’s an eager audience. The Direct Selling Association (DSA), the trade group representing MLMs, says that 51% of the 51 companies that participated in a survey in early June said COVID-19 has had a “positive” impact on their 2020 revenue; 59% reported the same in a later survey. DSA president Joseph Mariano says some sellers have inflated the potential rewards of investing in their companies. “You inevitably have a few overzealous people saying things that perhaps they shouldn’t,” he says. “When you have a vulnerable population of people who have lost their jobs or are concerned about losing their jobs, the fact of the matter is … direct selling is generally a modest supplemental income opportunity. It’s not something that is going to make you rich.” Mariano says the DSA has worked with the Better Business Bureau to monitor claims about products’ benefits and sellers’ potential earnings. The DSA-funded Direct Selling Self-Regulatory Council has referred four cases to the FTC this year for investigation of possible falsehoods.

But recessions tend to be good for MLMs, and this recession shows no sign of abating as new COVID-19 outbreaks slow reopenings. During the 2007–09 Great Recession, the number of MLM sellers began rising and went from 15.1 million in 2008 to 18.2 million in 2014, according to a DSA report.

Celebrity support helped. Soccer star Cristiano Ronaldo, lifestyle guru Rachel Hollis, former Presidents George W. Bush and Bill Clinton (after they’d left office), and private citizen Donald J. Trump have, over the years, appeared at MLM events or endorsed companies. Many influencers and athletes still back them, as distributors sign on to sell everything from leggings to home cooking products.

At most MLMs, investors, who are also known as distributors or sellers, make money by selling a company’s products and recruiting others to do the same. They then earn commissions or bonuses based on their recruits’ sales. But after investors have recruited as many friends and relatives as they can find, communities become saturated, making it difficult for new sellers to find customers. Countless distributors end up wallowing in merchandise they can’t sell and sinking into debt as they’re pushed to spend more money attending training seminars and bonding conferences, critics say. “They tell you if you don’t go to a training, if you miss a single training, you will never be successful,” says Illyssa Demarino, 31, a Phoenix bartender who tried three MLMs and spent thousands of dollars without making any money. “It’s so easy to get wrapped up in the cultlike mindset.”

MLMs fashion themselves as alternatives to the gig economy, which has been hit hard by COVID-19; apps like Uber are suffering as people avoid shared transport, while others, like Instacart and Doordash, are flooded with new workers, driving down gig pay. The MLM world implies a glamorous and safer alternative, and its prime target is women, who have been hit especially hard in this recession. Their service-sector jobs were the first to go when restaurants, bars, hotels and casinos closed, and when babysitting and housekeeping jobs ended.

Even before the pandemic, MLMs adopted the language of pop feminism with hashtags like #bossbabe and #momtrepreneur. Some sellers post doctored before-and-after photos for fitness and beauty products online in hopes of selling not just a payday but unattainable beauty.

“I was the perfect target,” says Jamie Ludwig, who in 2014 was convinced by a friend that she could make good money working from home in Kansas City, Mo., while selling weight-loss shakes and other supplements for an MLM called AdvoCare. “A new mom with baby fat I wanted to lose, desperate to be at home with my kids.” New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees endorsed the company, which in Ludwig’s eyes gave it an air of legitimacy.

She and her husband Josh bought a $79 starter kit, and she scaled back her hours as a hairdresser to devote time to AdvoCare. All they had to do, their recruiter told them, was find enough buyers for the $900 in supplements that arrived on their doorstep each month. “I spent the entire time on the phone trying to sell, giving my kids no attention, working 50 or 60 hours a week, more than I did before,” says Ludwig, 39. She and her husband, who is 41, found only a handful of buyers. They gave up AdvoCare 18 months later, but not before spending about $300 (plus transportation, food and housing) to attend a three-day “success school” sponsored by AdvoCare to learn sales techniques. When their car broke down on the trip, the couple was forced to face their financial straits. For years, Ludwig could not bring herself to look at the boxes of unsold shakes in her pantry.

AdvoCare is one of a handful of MLMs that the FTC has declared a pyramid scheme. According to the agency, 72% of AdvoCare’s distributors made no money in 2016, and 18% made $250 or less that year. After its investigation, the FTC in October 2019 required AdvoCare to pay a $150 million settlement and to stop using the MLM business model. (AdvoCare said in a statement that it “strongly disagree[s] with the FTC allegations” but has changed the way it does business.) One month later, the FTC alleged that Neora, an MLM selling supplements and skin creams, was a pyramid scheme. (Neora asserted that it was “not a pyramid scheme under the law” in its own lawsuit against the FTC, where it accuses the agency of reinterpreting laws to unfairly label it.)

In the past 41 years, the FTC has filed cases against 30 MLMs alleging they were pyramid schemes, according to Truth in Advertising, an independent watchdog group. In 28 of those cases, courts either agreed with the FTC or companies paid settlements or changed their business plans to resolve the cases. But the number of MLMs makes it difficult for the FTC to make sure each one is operating lawfully, especially since the number is always in flux. The Direct Selling Association estimates that 1,100 MLMs are in operation in any given year but cannot be sure. “Many companies may even come and go before they could even be ‘counted,'” the DSA says on its own website.

MLMs are not illegal, but many are at best financially risky. The chances of financial success are so grim that the DSA president, Mariano, has called participating in MLMs an “activity” rather than a job.

The numbers that MLMs report often paint a dark picture for sellers. At Young Living, 89% of U.S.-based distributors earned an average of $4 in 2018, according to an income-disclosure statement. At the skin-care MLM Rodan + Fields, 67.1% of sellers had an annual median income of $227 in 2019. More than half the distributors at Color Street fell into the company’s lowest tier of earners in 2018, with average monthly profits below $12.

As the industry grows, so does awareness. Data obtained by TIME through Freedom of Information Act requests shows that consumer complaints to the FTC about MLMs have risen in recent years. From 2014 to 2018, complaints against Amway, a company co-founded by Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’ father-in-law, went from 15 to 36; in those complaints, consumers reported losing a total of more than $380,000. Complaints against SeneGence, a makeup and skin-care MLM, jumped from two in 2016 to 14 the following year before falling to six in 2018; consumers reported total losses of nearly $25,000. Complaints against Monat, whose hair products stand accused of making people’s hair fall out, jumped from two to 30 from 2015 to 2018, with consumers alleging losses totaling $7,572. (Monat says its products are “dermatologist-tested” and that its research indicates they are safe.)

But the resources and time required to determine if a company is operating a pyramid scheme make it impossible for the FTC to investigate every MLM with questionable practices, experts say. “It’s like a policeman trying to stop cars that are speeding on a highway,” says Peter Vander Nat, a retired FTC economist who spent more than two decades representing the government in cases against MLMs. “For every one that it stops for speeding, five roll on by.”

States have taken up some of the burden, with Washington, California, Illinois and others representing plaintiffs in suits against various MLMs. But legal action has become increasingly challenging as more companies insert clauses in contracts that force sellers into arbitration rather than litigation in open court. Even if the MLMs are forced to settle for millions in arbitration, their wrongdoing doesn’t become as public as a court settlement.

According to the DSA, 74% of MLM sellers are women, and 20% of sellers are of Hispanic origin, a demographic that critics say highlights the industry’s systemic targeting of economically vulnerable communities. José Vargas, a 39-year-old from Connecticut, is one Latino man who suffered. After the mid-2000s real estate crisis forced him out of his career in the mortgage industry, he was struggling to support his family as a cable technician. He was also about 25 lb. overweight.

Enter Herbalife Nutrition, which since its founding in 1980 has sold dietary supplements. Vargas started buying Herbalife’s shakes in 2012 and was so happy about his weight loss that he became a full-time Herbalife distributor in hopes of making a better income and helping others get in shape. But as he shed the pounds, his wallet got lighter too. He says he paid about $2,500 for the privilege of calling himself a supervisor, which he was told would help him earn more money faster. He paid roughly $700 a month to rent space for a storefront, which was recommended as a way to build up a clientele. He says he attended mandatory local training sessions and “highly encouraged” national events in faraway cities. By the time Vargas gave up Herbalife in 2014, he says, he had lost close to $10,000.

Approximately 30% of Herbalife’s distributors are Latino, according to the company. Herbalife in particular has faced criticism for targeting low-income Latino sellers in Mexico and California. The company has a 10-year, $44 million sponsorship of the Los Angeles Galaxy professional soccer team, which boasts a massive Latino fan base.

“You have a lot of Latinos that come here, looking to achieve the American Dream and become successful,” says Vargas, who is back to working as a mortgage consultant. “I think it’s a big smack in the face.”

A 2016 FTC complaint accused Herbalife of deceiving consumers and portrayed issues in tune with Vargas’ experiences. Among other things, it said Herbalife banned storefront operators from displaying prices for anything other than Herbalife membership fees.

Herbalife evaded official classification as a pyramid scheme, but only barely. Then FTC chairwoman Edith Ramirez said the company was “not determined not to have been a pyramid.” Herbalife said it believed “many of the allegations made by the FTC are factually incorrect,” but it agreed to pay $200 million to consumers who the FTC said had been incentivized to recruit people to buy Herbalife products–whether or not there was a market for them.

Vargas recalls getting about $600 in the settlement but says worse than his financial loss is that he persuaded others to join Herbalife. Herbalife still operates in the U.S., but its biggest regional market is overseas in the Asia-Pacific region, where FTC rules don’t apply. (Herbalife says it has made significant changes since the FTC settlement to better protect distributors, such as compensating distributors based on how much they sell to customers rather than how much they personally buy, and requiring distributors to be with Herbalife for a year before opening a storefront, but some changes are not yet in effect in non-U.S. markets. In 2016, Herbalife said the settlement with the FTC showed that its “business model is sound.” Company officials declined to comment on the record for this article.)

Its website also invokes COVID-19 as a reason to trust its products, which it says have earned Herbalife the designation as an “essential” business.

On April 29, Vargas’ former Herbalife recruiter messaged him on social media after being out of touch for several years to ask how his family was faring through the pandemic. Vargas, suspecting the conversation would turn into a recruitment pitch, stopped responding after exchanging pleasantries. This time, he won’t be swayed. “What they promise,” he says of MLM distributors, “is very undeliverable.”

Beachbody CEO Carl Daikeler, who is 56 and estimated by Forbes to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, says that achieving his level of success by selling Beachbody’s shakes and recruiting others to do so isn’t easy. “This is not something you jump into and instantly make a lot of money,” he tells TIME. Daikeler says he sounds a warning to those who want to quit their jobs and be full-time Beachbody coaches. “I will literally say, ‘Are you sure? And do you have money saved? Because this is starting your own business, and starting your own business is very hard. Most new businesses that start, fail.'”

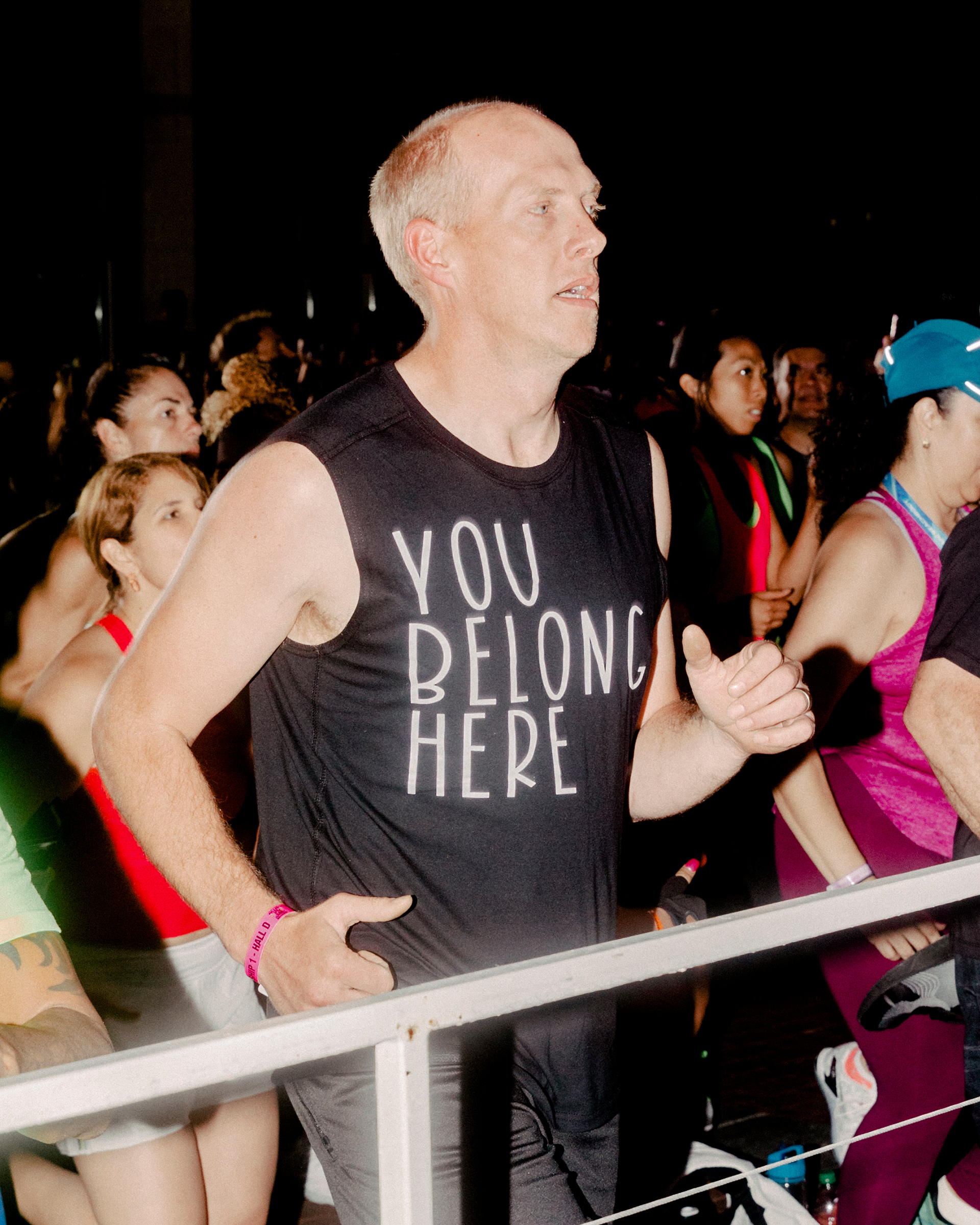

It is months before COVID-19 had become a household term, and thousands of Beachbody distributors have gathered in Indianapolis to be inspired, to be motivated and to learn how they can turn the hours they’ve devoted to Beachbody into a profit–or at least earn back what they’ve spent on the company’s products and on attending this three-day conference.

A fit man with close-cropped gray hair, Daikeler uses the gathering to announce an array of products to sell: an exercise program designed by a celebrity coach, a plant-based chocolate almond crunch bar, a pumpkin-spice protein beverage. “We have 300,000 coaches,” he says to wild cheers. “And we need to find the next 300,000.” The words I can be my own boss had just flashed on the screen behind the stage he’s now standing on.

Rachel Hollis will take the stage at some point, but Daikeler is the person thousands of people in that audience want to be.

One of the people in the crowd is LindsayAnn Hammarlund of Atlanta, a mother of three who left her teaching job two years after joining Beachbody, when her sales surpassed her teaching salary. “We were paying so much in day care, and I cried literally every single day I took them to day care and I went to school,” says Hammarlund, 35. She’s recently gone back to the classroom now that her kids are older. But that MLM income, she says, has enabled her to pay down debt and take “many trips” with her Beachbody team. Dozens of other coaches who attended the Indianapolis convention told TIME they signed up because they liked the products, enjoyed the camaraderie and wanted to get in shape–not because they wanted to make money.

But on its website, Beachbody emphasizes that being a coach “means earning an income while you help yourself and others live healthier.” Except that wasn’t the reality for more than half of its coaches last year: 57% of them earned $0 in commission and bonuses in 2019, according to the company’s income-disclosure statement. Andy Brown, 38, a former Beachbody coach, thought he’d made between $4,000 and $5,000 in 2015, until he did his taxes. “I was starting to estimate how much money I spent on everything compared to the amount of money that I actually made, and that was sort of a wash,” says Brown. “And then on top of the tax hit I took, that’s when I was like, I’m in the red. This isn’t helping me at all. In fact, I’m probably worse off than when I started.”

Christine Baker, who left Beachbody in 2017, says she was paying about $100 per month to remain an active coach, but her highest commission check was $300. (Beachbody says it is possible to remain active by purchasing or selling as little as $67 worth of product per month and paying a $15.95 monthly fee.) Like Brown, Baker says the truth hit her around tax time. She recalls her accountant telling her, “You know, the only reason why you’re doing half good on your taxes this year is because you lost so much money.”

The same year Baker left Beachbody, a judge in Santa Monica, Calif., ruled the company must pay $3.6 million in penalties and restitution after the city accused it of charging customers’ credit cards for renewal fees without consent, and of exaggerating its products’ health benefits. Now, Beachbody must clearly define renewal terms, obtain consent from customers for subscription renewals and support its health claims with “competent and reliable” scientific studies.

That hasn’t deterred customers. Since COVID-19 closed gyms, Beachbody’s business has been booming. Daikeler tells TIME that April, May and June were the top streaming months for Beachbody on Demand workout videos since the program launched in July 2015: the number of subscribers has blossomed more than 33% since mid-March, and customers are averaging 600,000 fitness classes on the platform per day.

And a lot of these customers are attempting to turn their newfound workout regimens into income streams. Of the approximately 405,000 Beachbody coaches who are eligible to recruit participants and make money off them, more than 141,000 signed up on or after March 1.

With Reporting by CURRIE ENGEL/NEW YORK

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Abby Vesoulis at abby.vesoulis@time.com and Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com