From the hotel terrace where he ate breakfast, Phil Pelzer could almost pretend nothing had changed. Yes, the maître d’ had aimed a temperature gun at his head before allowing him near the buffet. And he wouldn’t usually serve himself eggs in gloves and a mask.

But the friendly waitresses still addressed him in halting German, and the sun still warmed his pale, tattoo-covered arms. For Pelzer, a plumber from Alsdorf, Germany, who has long taken his annual vacation on the Spanish island of Mallorca, the important things were still in place. “There’s still sun, there’s still sand,” he said. “Maybe it’s not quite so much fun as before, but it’s still a holiday.”

On that wan enthusiasm rests a continent’s hopes. Pelzer and his family were among the 400 or so German tourists who traveled on June 15 to Mallorca as part of a pilot program run in collaboration between the tour company TUI and the Balearic Islands’ regional government. It was originally conceived as a way for both the vacation hot spot and the tour company to test their preparedness to once again receive visitors after months of lockdown. But even before the Pelzers boarded the plane in Düsseldorf, Spain had decided it couldn’t afford to wait to learn the results. On June 21, spurred by both economic necessity and its neighbors’ rush to open, the Spanish government formally ended its state of emergency and opened its borders again to European tourists.

As much of Europe abandoned its mandatory quarantines and followed suit, the pilot program was watched across the continent with acute interest and no little anxiety. TUI had sold out the two flights in a matter of hours. But would that level of interest be sustained? Would it be enough to offset the loss of American and Asian tourists whose return might still be months away? Would it be safe for both the visitors and the locals who received them? And would making them safe–with all the personal protective equipment and social distancing required–turn a relaxing break into something more closely akin to a hospital stay?

As Europe begins its recovery from the coronavirus pandemic, countries are attempting to find a middle ground between protecting public health from a virus that still poses a threat and reviving moribund economies. Perhaps no sector faces higher stakes than tourism. It was, after all, travel that supercharged the pandemic, allowing a virus to move from the markets of Wuhan, China, to the ski resorts of Italy, the conference halls of Germany, and the ports of Japan and California. And in the absence of a vaccine, it’s clear that tourism’s necessary components–not just its airplanes and cruise ships but also its hotels, restaurants, museums and festivals–remain important vectors for the virus’s potential transmission.

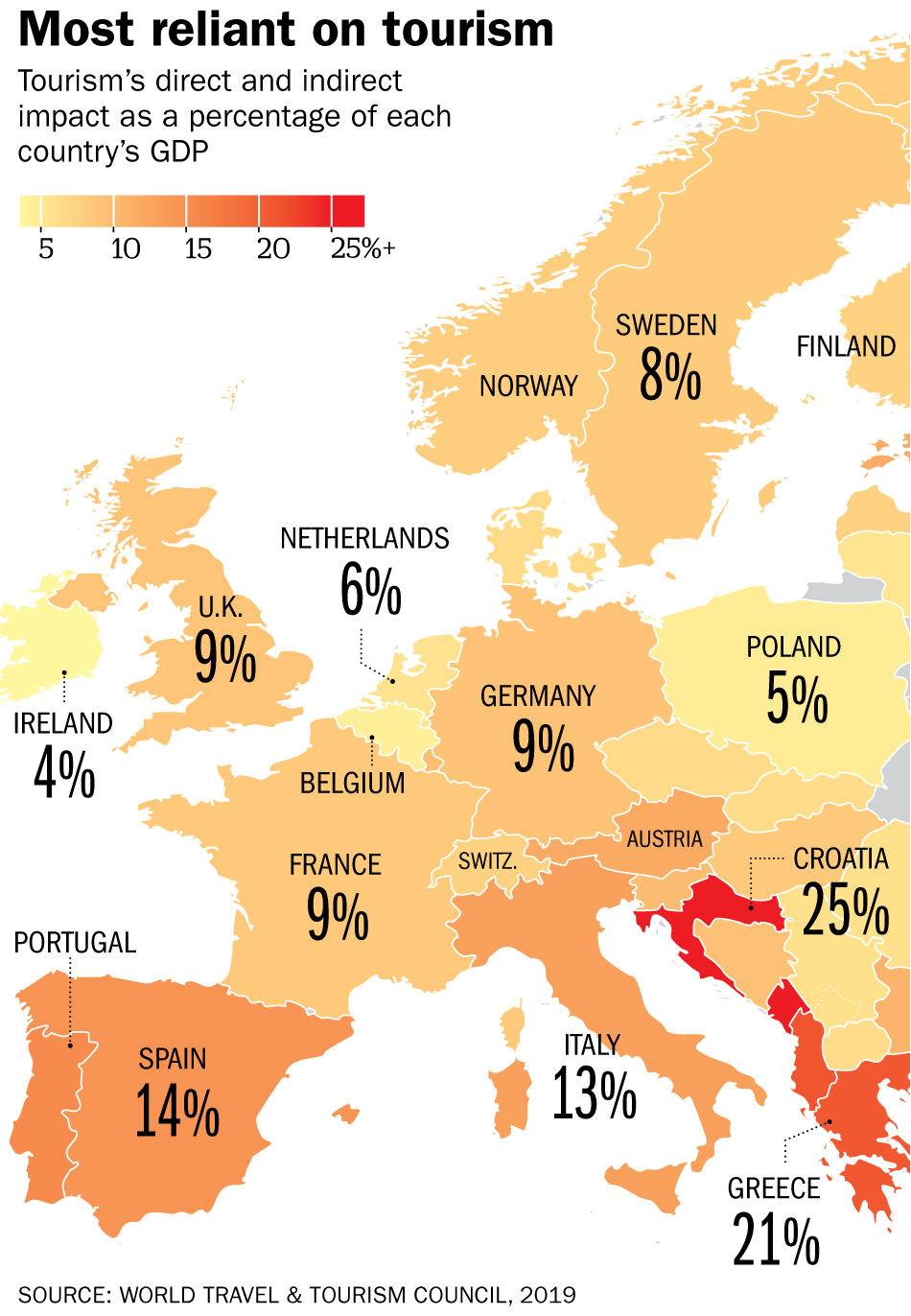

Yet in Europe especially, tourism is also critical to the economy. In the 27 nations that make up the European Union, up to 11% of the collected GDP derives directly from tourism (compared with 2.6% in the U.S.). In Paris alone, tourism represents the single largest industry, bigger even than services or fashion, and the 38 million who visit the city annually keep nearly 12% of all working Parisians employed. “It’s been a cliff, vertigineux,” says Paris Deputy Mayor Jean-François Martins of the drop-off brought about by the lockdowns. “There will be millions and millions of Paris visitors missing from the beginning of the crisis until we get back to normal.”

The pain stretches up and down the food chain, from stalwart airlines like Lufthansa and SAS that are teetering on the brink of bankruptcy to small companies like Athens Insiders, which organizes everything from afternoon tastings at Athens markets to weeklong archaeological tours. “When Greece locked down in mid-March, we had 100% cancellations,” says Anthia Vlassopoulou, the CEO and a co-owner of the 18-person company. Because it caters primarily to American tourists, she doesn’t expect any of them back until 2021. “We predict revenues will be down 90% for the year,” Vlassopoulou says. “Our only hope is persuading our clients to postpone their trips rather than canceling them so that we don’t have to refund their deposits.”

Government bailouts and unemployment subsidies have kept many–though by no means all–enterprises on life support during these past few months, but as countries pull back assistance, the projections are dire. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, Europe is on track to lose 18.4 million tourism-related jobs and $1 trillion in GDP in 2020. It might seem trivial in the context of a global health emergency, but finding ways for Europeans like Phil Pelzer and his family to safely enjoy a summer vacation could provide a lifeline to millions of people.

It could also be crucial to Europe’s future. Just like the debt crisis of a decade ago, the coronavirus poses a threat to an already fragile European unity. The economic and political bloc relies on multilateral cooperation, open borders and free movement of people–all of which were tossed out the window during the worst of the crisis. As they cautiously reopen, each European country is taking its own approach to border controls and health protocols. But rebuilding a tourist economy is something they must do together. If they succeed, European unity might just come out stronger.

As the coronavirus began to proliferate outside China, Europe was among the first places to feel its full impact. Although the first cases were detected in France, Italy quickly became an epicenter and the first European country to impose a draconian lockdown. There and in a few other countries like Spain, France and the U.K., infection and mortality rates spiraled almost out of control. Other countries, like Germany, have had relatively high infection rates but managed to avoid the devastating rate of mortality through a combination of extensive testing and quick action. And then there are a handful of places like Denmark and Greece that, through a still mysterious combination of good policy and good luck, have managed to avoid the full brunt of the disease.

The majority of countries in Europe are now well past the peak of their outbreaks. During the spring, when it became clear that the summer season would be limited at best, many began investigating the creation of so-called corridors or bubbles that would allow citizens of areas that appeared to have the virus under control to travel safely. “The idea is to create ‘green zones’ that would first unite geographic areas where the virus was under control and economic activity could be restored,” says Bary Pradelski, an economist at France’s National Centre for Scientific Research. He and colleague Miquel Oliu-Barton wrote an article on the European policy think-tank site VoxEU in late April that would prove influential in how both France and Spain approached their reopenings. The plan, he says, would be to “bridge those zones with others in a similar situation.”

The Baltic states, for example, united in mid-May to allow citizens of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia to visit one another’s countries unimpeded. More recently, Denmark opened its doors to Germans, Norwegians and Icelanders–though not its neighbors in Sweden, which has substantially higher infection and mortality rates. The E.U.’s leadership endorsed the approach, noting in a report on May 13 that “handled correctly, safely, and in a coordinated manner, the months to come could offer Europeans the chance to get some well-needed rest, relaxation and fresh air, and to catch up with friends and family in their own member states or across borders.” But as Pradelski points out, that coordination hasn’t been entirely forthcoming. “The earliest zoning just conformed to national borders, which had nothing to do with the realities of the virus,” he says. “Now we’re seeing bilateral agreements, but we hope they’re just the starting point.” He hopes the E.U.’s executive body will set Union-wide benchmarks for testing and border controls. “Unless we find common standards, people are not going to feel safe. And then there will not be enough demand for tourism.”

But these will always be guidelines; ultimately, individual member states call the shots over their own borders. As a result, the current situation is a sometimes bewildering patchwork of exemptions. Austria, for example, has chosen to bar visitors from Spain, Portugal, Sweden and the U.K. Greece requires a test for the virus from anyone arriving from Italy, Spain, the Netherlands and Sweden, among others. Even Denmark, which on June 18 announced it was opening its borders, continues to bar entrants from Sweden, one of the few countries in Europe still seeing new case numbers rise. All member states are currently haggling over which non-E.U. countries sufficiently meet health and other criteria to be permitted in July and beyond. (And it doesn’t look good for the U.S.)

The dire economic situation doesn’t necessarily encourage member states to cooperate and may, in fact, be fostering a sense of competition. Being first out of the gate was certainly part of the calculation for Mallorca’s pilot program. “We wanted to verify the protocols we had put into place,” says Iago Negueruela, the minister of tourism for the Balearic Islands’ regional government, “because we knew that as islands coming out of this in the summer, we would be [popular with tourists]. But we also wanted to do it because it allows us to position ourselves, with regard to Europe as a safe destination. The fact of being first has its own potential.”

In some ways, Mallorca, the largest of the Balearics, is the perfect microcosm for a Europe attempting to recover from the pandemic. A relatively early and near total shutdown allowed the chain of Balearic Islands in which it sits to avoid the kind of carnage experienced in Madrid and Barcelona, but the island’s outsize reliance on tourism–34.8% of the GDP–makes it highly vulnerable to whatever comes next. And because neither American nor Asian tourists travel to Mallorca in great numbers (Germany and the U.K. are its biggest markets), it offers a clear reflection of how the rest of the continent might welcome visitors from a range of nearby countries.

“It matters that we were the first to do this,” Negueruela said after the first flights landed. “We were on the news in every country last night, and we’re seeing it have a bandwagon effect, with more flights being announced and more hotels opening. There is a kind of competition with other regions and countries, so it’s good to be out there first.”

But internecine rivalry for the same diminished pool of visitors isn’t the only divide the crisis has opened. In March, wealthy northern countries refused to send medical aid to the harder-hit south or to issue joint bonds that could mitigate recovery costs. Italy, in particular, was furious. In April, European Commissioner Ursula von der Leyen apologized to the country for the E.U.’s lack of solidarity, but the damage had already been done. “At the beginning of this crisis, COVID-19 showed all the European Union’s weaknesses,” says Irene Caratelli, the director of the program in international relations at the American University of Rome. “To meet a transnational crisis by closing national borders was idiotic. It seemed that we’re only European when we’re growing economically. When there are costs, the national borders come back up.”

Caratelli has been encouraged, however, by more recent collaborations. At the end of May, the Commission proposed a €750 billion ($845 billion) aid package to jump-start the recovery in the hardest-hit countries and protect the single market from being splintered by levels of wealth and economic growth. The so-called frugal four–Austria, Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark–continue to resist supporting the more indebted (and tourism-reliant) countries to their south. But more crucially, Germany, the bloc’s largest economy, which insisted on punishing austerity reforms for hard-hit economies post-2010, has softened its hawkish stance and backed a joint recovery plan. “It’s starting to seem now, paradoxically, that this is the kind of crisis that could trigger the European Union to go in a more federalist direction,” Caratelli says.

Yet the simple realities of travel in this pandemic age aren’t doing the E.U. any favors. One of the most visible benefits of the E.U. for ordinary citizens–the freedom of movement across open borders–has, at least for the time being, disappeared. Passengers on the two packed planes that landed in Palma de Mallorca on June 15 from Germany had to fill out two separate lengthy forms before they could disembark, then undergo temperature scans, interviews and the kinds of passport checks not seen within most of Europe in decades.

Once they made it through all the checkpoints at the Mallorca airport, the pilot-program travelers encountered a wide gamut of protocols intended to keep them, as well as locals, healthy. Some of these were invisible; at the two Riu hotels where they were lodged, occupancy had been cut to 50%, with entire wings set aside in case it became necessary to quarantine anyone; cleaning personnel wiped down surfaces with color-coded cloths and disinfected rooms with a powerful antiviral. Other measures were highly visible; in addition to undergoing temperature checks every time they entered the dining room, guests had to wear masks in public areas and avail themselves of one of the 70-odd bottles of hand sanitizer placed around each hotel.

For Txema Delgado, who has been working as a pool attendant at the Riu Concordia for four years, the new routines mean a lot more work. He now has to thoroughly disinfect every deck chair after it’s used and wipe down every handrail within five minutes of a guest’s touching it. “But I don’t mind,” he says. “I think it reduces the guests’ fear. They seem very calm and happy, almost like nothing’s happened.”

Out on the boardwalk, Christian Laforcade would like to be able to say the same thing. With his signature bandanna wrapped around long curly hair, he has overseen the venerable beachfront restaurant Zur Krone since 2007, cheerfully serving bratwurst and aioli to the German tourists who are the primary visitors to Platja de Palma, the resort area east of the city. Laforcade reopened the restaurant in May to serve whatever locals were around. “I’m the brave one,” he said with a smile as he gestured down an otherwise abandoned boardwalk. “Or the crazy one.”

And he couldn’t hide his economic concerns. “In this business you make most of your money in just a few months. By October, it’s over,” he said. “We’ve lost March, April and May entirely. And June is not looking good. Normally this time of year we’d be serving 60 to 80 breakfasts a day. How many have I served today? Zero.” Pedro Martin, who owns another restaurant, La Celta, two doors down, said he would be staying closed for the foreseeable future. “I don’t trust it yet,” Martin said about when he might reopen. “I won’t trust it until we see the planes in the sky and we know that those planes are full.”

Business owners may be desperate for the streets of Palma to be filled with drinking, carousing tourists–but other locals aren’t so sure. A schoolteacher who works in Magaluf, Montse Guasch says she personally doesn’t miss the kind of turismo de borrachera (drunk tourism) the town is known for. She’s also delighted that she is able to snag an outdoor table at a city center bar during peak hours. She is aware tourism has to return for the good of the local economy, she says. “I just hope it comes back different: higher quality, more respectful, more sustainable for the environment.”

She is hardly alone. In the years leading up to the pandemic, another kind of crisis was building throughout Europe as tourist numbers surged uncontrollably. Tour buses, low-cost airlines and gigantic cruise ships delivered masses of sightseers to historic city centers, disrupting local housing markets, damaging the environment and turning entire neighborhoods into no-go zones for residents. Now, with the rupture that the pandemic has brought, many see an opportunity to reduce tourism’s negative impact and remake it into something more sustainable.

Perhaps in no place is that case stronger than Venice, where tourist numbers have been so great that the municipal government tried imposing turnstiles at the city’s main entryways to control access. Vacillating administrations have never managed to apply long-standing proposals to restrict the number of short-term rental apartments or to redirect cruise ships. But where they failed, the virus has succeeded. “For the first few weekends it was only people in the [local] region who were allowed,” says Francesco Semenzato, a co-founder of Venezia Non è Disneyland (Venice Is Not Disneyland), a citizens’ platform that draws attention to the impact of mass tourism on the city. “And lots of them came … they saw it as an opportunity to take back their city. Even now, when it’s open to other Europeans, it feels different. Before it was a lot of day-trippers and people who came just to check Venice off their list. Now you can tell that people are interested in what is really here. If tourism was like this for the rest of our lives, it would be amazing.”

Although Semenzato doesn’t place much hope in the local government’s backbone to impose change, he hopes that one of the pandemic’s by-products–a chance to experience their city as a real, livable place–will give Venetians the will to fight for stricter regulations. His sentiments are shared by Paris’ deputy mayor. “We can take the decision to make this crisis an opportunity to reinvent tourism,” Martins says. “We want to go from mass tourism to tourism that melts into the mass.” To that end, the city is weighing measures that include a ban on giant tour buses and a limit on districts with Airbnb apartments.

Whether there will be enough collective will to see these kinds of measures through during a time of economic hardship and even recession remains unclear. But many countries are trying to buffer the potential losses by promoting the staycation–and opening up the potential of summer vacations to the underprivileged. Italy is issuing vouchers of up to €500 ($565) to families that earn below €40,000 ($45,100) a year and choose to travel domestically, while Spain just launched an expensive, if somewhat melodramatic, ad campaign heralding the glories of a holiday at home. “This summer will be the opportunity of a lifetime,” Martins says. “You can go to the Louvre, and no one will be there!”

Of course, all these recovery measures could quickly come to a halt if cases surge again. Those fears were on the mind of one employee at the Riu hotels, even as she expressed relief to be working again. “Just today they announced an outbreak at a meatpacking plant in Germany–1,000 people infected,” said the hotel worker, who requested anonymity in order to speak freely. “What if one of those people comes here? I have my parents and children to take care of. I worry a lot about getting sick.”

For his part, Phil Pelzer felt safe. “The hotel seems to be taking a lot of precautions. And we’ve been wearing masks back in Germany, so that didn’t bother me,” he said, as he and his family headed off to pick up their rental car for a day they planned to spend touring the island’s interior. In many ways, he represents the kind of tourist Europe is banking its hopes on: family-oriented, more interested in sightseeing and lounging on the beach than in getting wasted and, above all, willing to spread some cash around. “I don’t know if I’d say it’s my dream vacation,” he said. “But we’re still having fun.”

–With reporting by Vivienne Walt/Paris and Madeline Roache/London

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com