I hadn’t been speeding. I hadn’t been drinking. I hadn’t broken any laws. There was no discernible reason I could find for being pulled over by the police. Except for the obvious: I was driving through a wealthy white suburb, and something about me and my small Honda Civic stood out. To this police officer, I clearly did not belong there.

Hands shaking, heart pounding in my chest, I slowed and pulled over, then quickly found my driver’s license, registration and proof of insurance before the cop could make his way to my car.

It took him a long time to get out of the police cruiser. The longer I sat there, under the cover of darkness, no other cars passing, no other lights in the distance, the more I shook.

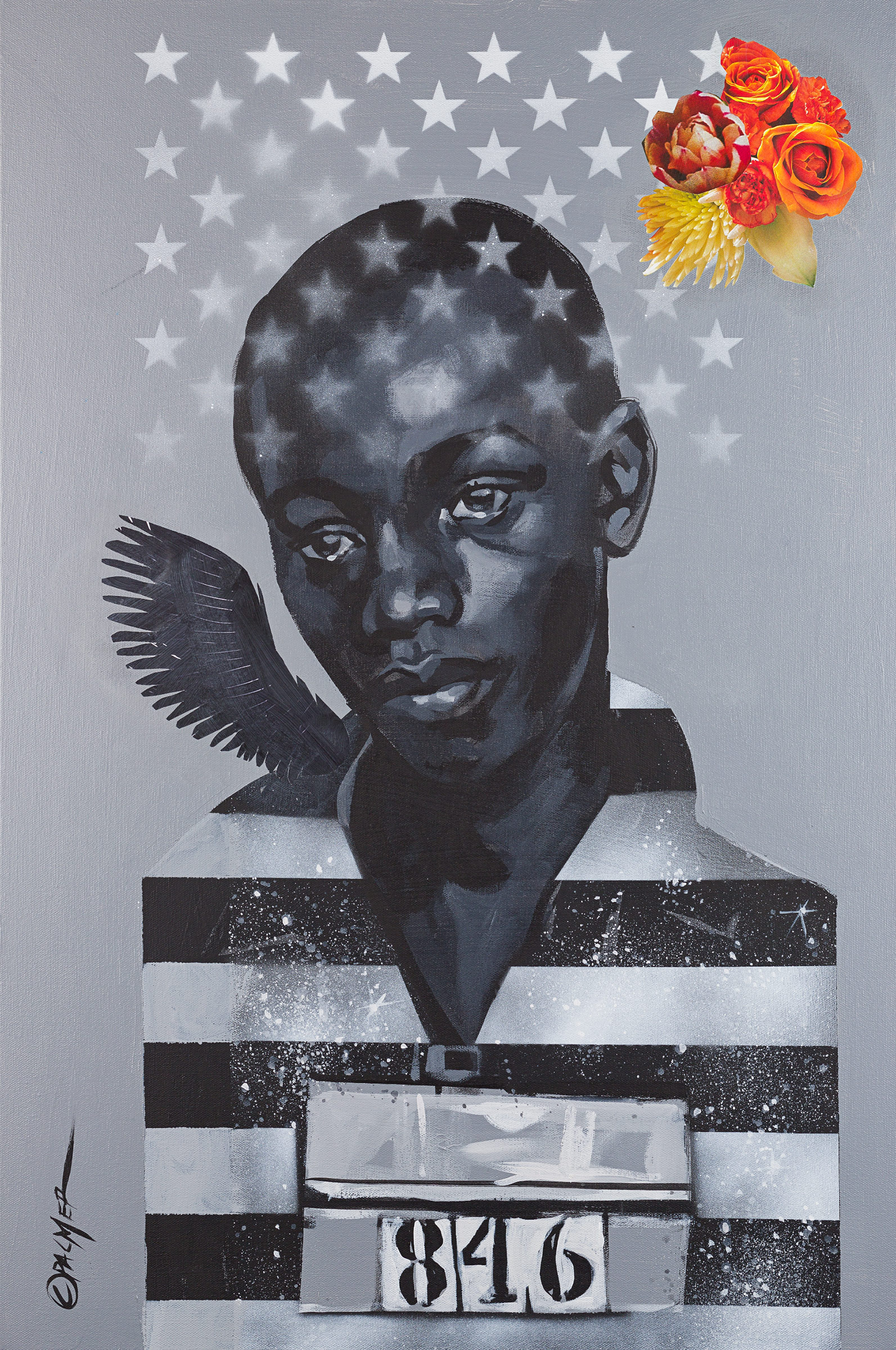

There is a trauma response with which some of us are all too familiar when encountering the police–anxiety, the urge to empty our bladders. We think, How do I make myself seem smaller, less dangerous? We think, How do I make him see that I’m polite, that I’m complying, that I’m not a threat? We think, How do I stay alive?

I held my documents out in front of me, placed the other hand on the steering wheel. I tried to look at his car in my rearview and side mirrors, but the cruiser’s spotlight reflecting off them was blinding. Then the silhouette of his uniformed body approaching, his hand reaching for his sidearm, a flicker of movement, the flashlight raised, and soon nothing. I couldn’t see anything except the bright-hot light in my face. But I knew, without a doubt, that he had drawn his weapon.

I was taught to fear the police.

In Puerto Rico, in el Caserío Padre Rivera, the government housing projects where I spent my childhood, the police were part of our everyday reality. We were a community that was overpoliced, under constant surveillance. To them we were dangerous. Born into poverty, most of us Black and brown, we needed to be controlled, to be kept in line.

We learned to avoid them, and when we saw them, to hold our loved ones close. We learned that our bodies, our homes, our spaces did not belong to us, but to them.

I grew up hearing stories about los camarones, freezing, hiding, running running running when I saw them pull up ready to storm the building next door.

I grew up hearing about Rey el Chino, a close friend of my father’s who’d been killed by los camarones when I was a baby. According to our neighbors, the cops took him as the whole block gathered outside, beat him as the crowd watched helplessly, as they called for them to stop. Then, los camarones shot him twice in the groin and tossed him in the back of the cruiser, where he eventually bled out.

Everyone talked about it. Everyone knew. A few years later, in 1984, Pedro Conga, who’d grown up in our neighborhood and later became a salsa bandleader with international acclaim, released a single called “Rey el Chino.” The song opened with two shots.

I don’t remember what I said to the cop that night in Miami. He asked if I lived in the neighborhood. I thought of my partner, alone in the small apartment we share in Montréal, our second home. He asked where I was coming from, where I was going. How to explain that I was a writer, that I’d just come from reading from my book to a crowd of strangers. Would he believe me? I thought I would piss my pants. I held it, hard. I thought of my mother in her bed, asleep by now, the message in my voice mail when I didn’t answer earlier because I’d been running late to the event.

Whatever I said, he believed, because he said good night, walked back to his car and drove away. Left me sitting there, breathing, shaking.

I am a Black Puerto Rican woman with a white mother, with light skin, and more often than not, people don’t read me as Black. Miami is a city made up of mostly white Latinxs, and the truth is, when he looked at me, this white cop did not see a Black woman, so he did not consider me dangerous. If he’d read me as Black, he might have read my Blackness as a threat. Maybe I wouldn’t have made it home. Maybe my trembling hands, my inability to control my own body would have been enough for him to see me as someone to fear, someone to be kept in line. But that night, I wasn’t shot by the police. I got to walk away. Shaken, yes, but alive.

I am the Black daughter of a white woman, which means that in my family tree there are colonizers as well as colonized people, and I carry this violence in my body. I see it in the mirror every day.

In the U.S., whether or not people read me as Black, I’m a racialized person: I’m Latina; my first language is Spanish; I have an accent. I’m also a gay woman with a white transmasculine fiancé. We spend part of the year in Canada because my partner is not an American citizen, and we’ve been navigating the complicated, expensive and exhausting system of U.S. immigration. During this pandemic, with the closing of borders, travel bans and the Trump Administration’s immigration proclamations, it’s only gotten worse: I haven’t seen my partner since March 14. We have no idea when we’ll see each other again.

Every day, the intersections of our identities as an interracial queer couple make living anywhere, moving in certain spaces, feel like a kind of negotiation. Montréal is very queer, so it feels relatively safe to be openly gay there, to hold my partner’s hand in public. They don’t have to worry about who they might encounter in a public restroom, because almost everywhere we go, we are surrounded by liberal, queer, genderqueer and transgender people. But in almost all of these queer safe spaces in Montréal, I am always the only person of color. In Miami, spending time in predominantly Latinx spaces often means having to deal with homophobia, transphobia and anti-Black racism.

Being openly gay with a trans partner, I’ve learned that simple things like using a public restroom, or just existing, can be terrifying. When we’re traveling together in the U.S., stopping at roadside gas stations on the interstate, even trying to get a hotel room, is often scary. Going through airport security checkpoints, where TSA agents almost always misgender my partner then flag them for a pat-down, is exhausting. Trying on clothes in department stores or finding queer-friendly barbers and doctors sometimes seem like impossible tasks.

My partner must always consider how they move, and for every single space they enter, if they will be safe. Often, walking down the street together or holding hands on the Metrorail in Miami, we’re met with strangers staring, random people making hateful and transphobic comments. More than once, my partner has been attacked in public changing rooms–once violently beaten by a group of teenage girls, and another time by a group of women demanding to see their genitals. We’re always thinking about who is watching, who is waiting outside that bathroom stall. I’m always thinking about what might happen on the days when they go out alone. What if I’m not there one day? Or what if I am there, but that is not enough?

My family came to Miami from Puerto Rico chasing the promise of a better life. My father believed he could take us out of our home in el caserío, work to lift his family from poverty. He believed that his children would go to school, that we would have health insurance, live happily. He believed that we’d be safe.

The truth is, some of us have always been in crisis. Some of us have never felt safe. Some of us have always been navigating systems of power and oppression in our homes, in our workplaces, in our schools, so we were not surprised by the last presidential election, because while some of America woke up to reality in November 2016, or even just last month, the rest of us have been waking up in this America since we were born or arrived here.

Over the course of the past few months, some of us have felt more targeted than ever. While the world watches, more and more videos of Black people being murdered are shared on social media, countless stories of protesters tear-gassed, shot, beaten, missing, dying in police custody, found hanging from trees, and the cops who killed Breonna Taylor still haven’t been arrested. While the world watches, a famous author with millions of social-media followers writes a transphobic statement to defend transphobic tweets, transgender health protections are reversed by the Trump Administration, Black trans women are brutally murdered one after another, and there’s still no justice for Tony McDade, for Riah Milton, for Dominique Fells, for Nina Pop, for Layleen Polanco, for Zoe Spears. Sometimes this feels like too much to bear.

On June 15, I sat in my living room talking to my partner on video. We talked while I waited for the Supreme Court decision on Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which protects workers from discrimination on the basis of sex. Shortly after 10 a.m., I saw the news: the Supreme Court had ruled that firing someone for being gay or trans was a violation of Title VII. I burst into tears, leaning back on the sofa, overwhelmed, completely shocked. It felt strange to get good news. It was a relief.

We have always been in crisis. But while the nationwide protests, led by Black women and Black LGBTQ people, are fueled by the fight for Black liberation, more people have been energized to protest all types of oppression. A growing number of Americans are becoming aware of their own roles in systemic racism, how they’ve been complicit, how they’ve benefited from systems of oppression and how they can be allies in the fight for Black liberation and LGBTQ rights. Three days after the Supreme Court’s Title VII decision, the court ruled that DACA recipients can continue to live and work in the U.S. without being deported.

The movement continues to rise, moving from the streets into classrooms, boardrooms, courtrooms, human-resources departments, publishing, media, film, television, retail, food and service. America is changing. The world is watching. And Election Day is coming.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com