Diseases and outbreaks have long been used to rationalize xenophobia: HIV was blamed on Haitian Americans, the 1918 influenza pandemic on German Americans, the swine flu in 2009 on Mexican Americans. The racist belief that Asians carry disease goes back centuries. In the 1800s, out of fear that Chinese workers were taking jobs that could be held by white workers, white labor unions argued for an immigration ban by claiming that “Chinese” disease strains were more harmful than those carried by white people.

Today, as the U.S. struggles to combat a global pandemic that has taken the lives of more than 120,000 Americans and put millions out of work, President Donald Trump, who has referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus” and more recently the “kung flu,” has helped normalize anti-Asian xenophobia, stoking public hysteria and racist attacks. And now, as in the past, it’s not just Chinese Americans receiving the hatred. Racist aggressors don’t distinguish between different ethnic subgroups—anyone who is Asian or perceived to be Asian at all can be a victim. Even wearing a face mask, an act associated with Asians before it was recommended in the U.S., could be enough to provoke an attack.

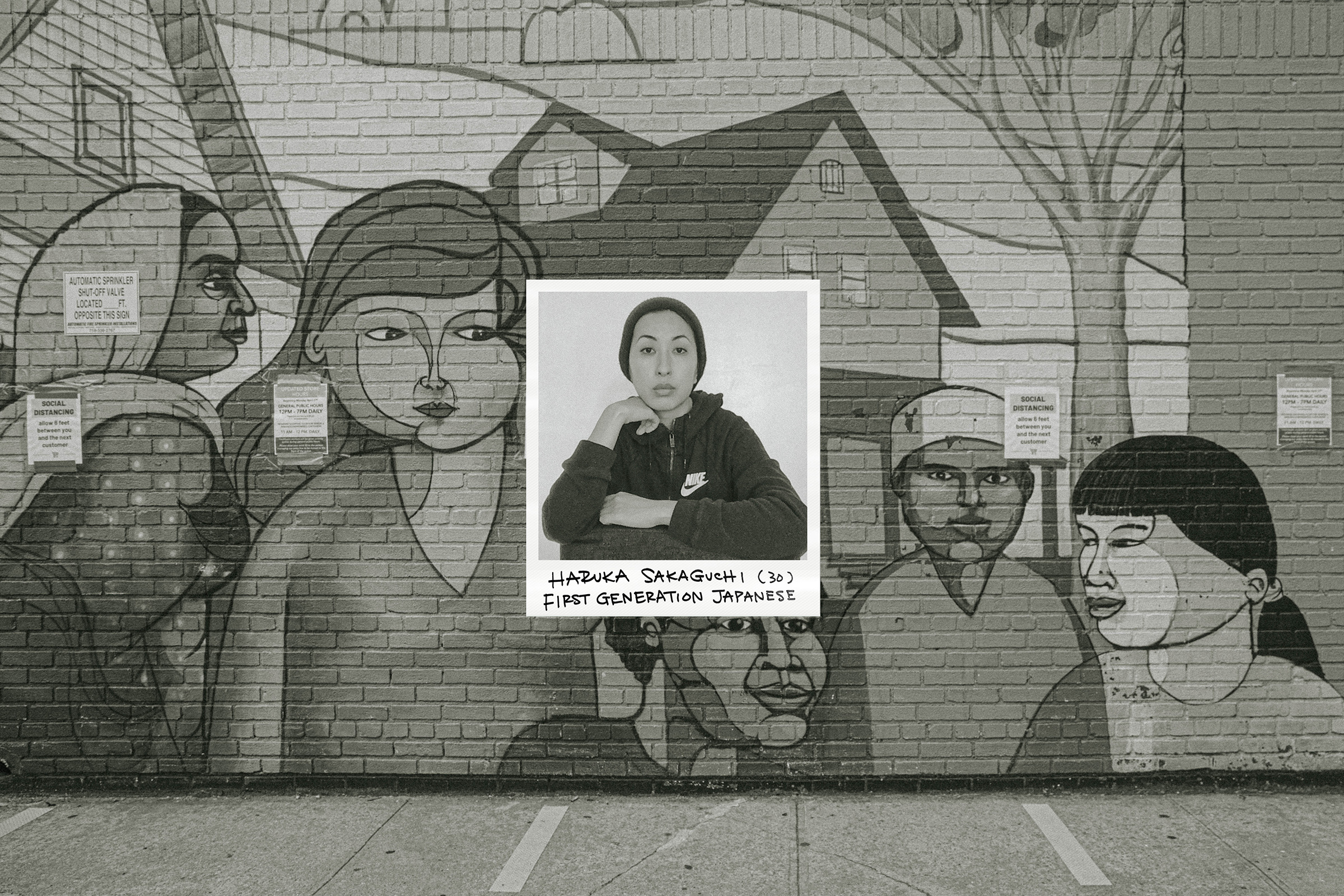

Since mid-March, STOP AAPI HATE, an incident-reporting center founded by the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, has received more than 1,800 reports of pandemic-fueled harassment or violence in 45 states and Washington, D.C. “It’s not just the incidents themselves, but the inner turmoil they cause,” says Haruka Sakaguchi, a Brooklyn-based photographer who immigrated to the U.S. from Japan when she was 3 months old.

Since May, Sakaguchi has been photographing individuals in New York City who have faced this type of racist aggression. The resulting portraits, which were taken over FaceTime, have been lain atop the sites, also photographed by Sakaguchi, where the individuals were harassed or assaulted. “We are often highly, highly encouraged not to speak about these issues and try to look at the larger picture. Especially as immigrants and the children of immigrants, as long as we are able to build a livelihood of any kind, that’s considered a good existence,” says Sakaguchi, who hopes her images inspire people to at least acknowledge their experiences.

Amid the current Black Lives Matter protests, Asian Americans have been grappling with the -anti-Blackness in their own communities, how the racism they experience fits into the larger landscape and how they can be better allies for everyone.

“Cross-racial solidarity has long been woven into the fabric of resistance movements in the U.S.,” says Sakaguchi, referencing Frederick Douglass’ 1869 speech advocating for Chinese immigration and noting that the civil rights movement helped all people of color. “The current protests have further confirmed my role and responsibility here in the U.S.: not to be a ‘model minority’ aspiring to be white-adjacent on a social spectrum carefully engineered to serve the white and privileged, but to be an active member of a distinct community that emerged from the tireless resistance of people of color who came before us.”

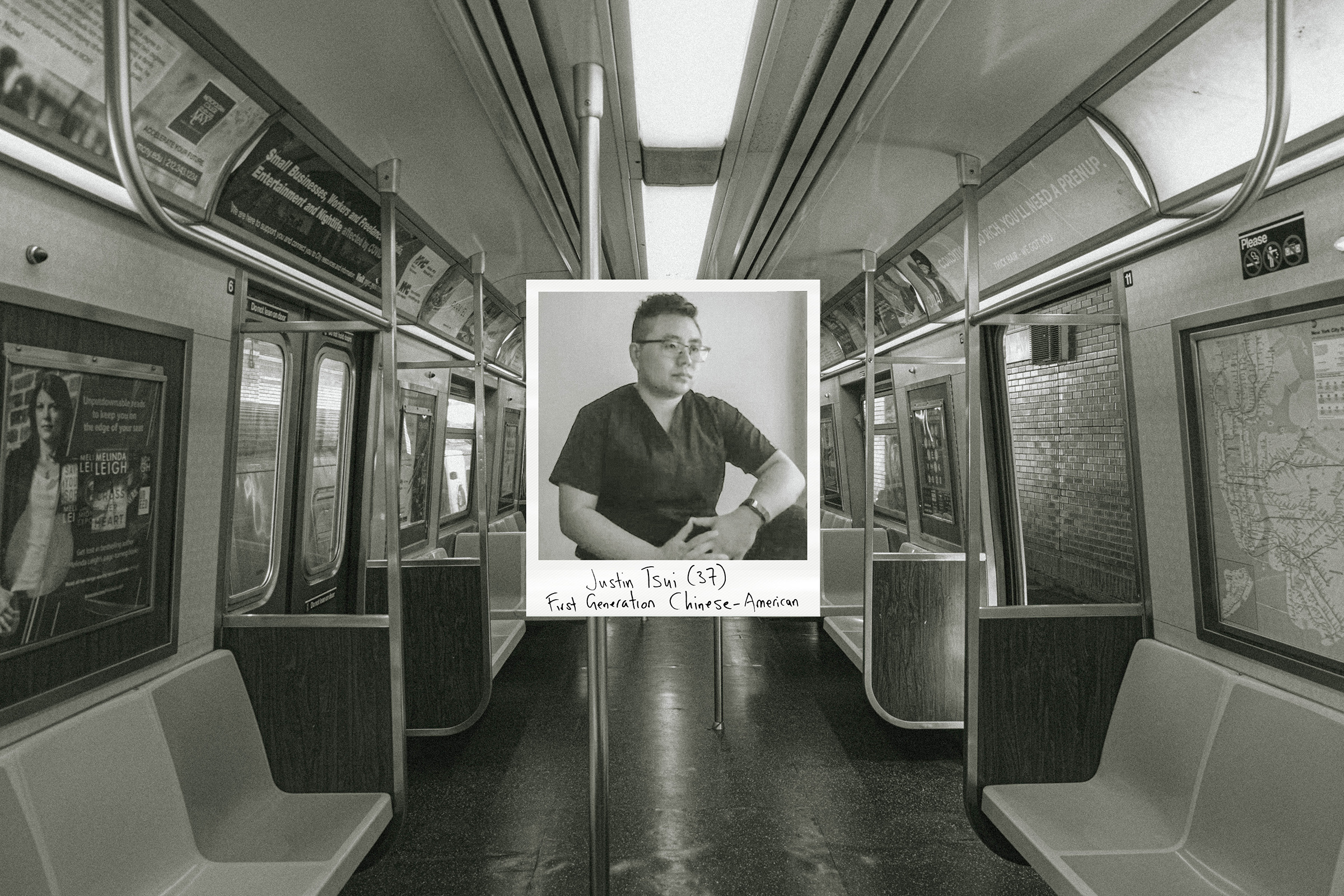

Justin Tsui

“I didn’t think that if he shoved me into the tracks I’d have the physical energy to crawl back up,” says Tsui, a registered nurse pursuing a doctorate of nursing practice in psychiatric mental health at Columbia University. Tsui was transferring trains on his way home after picking up N95 masks when he was approached by a man on the platform.

The man asked, “You’re Chinese, right?” Tsui responded that he was Chinese American, and the man told Tsui he should go back to his country, citing the 2003 SARS outbreak as another example of “all these sicknesses” spread by “chinks.” The man kept coming closer and closer to Tsui, who was forced to step toward the edge of the platform.

“Leave him alone. Can’t you see he’s a nurse? That he’s wearing scrubs?” said a bystander, who Tsui says appeared to be Latino. After the bystander threatened to record the incident and call the police, the aggressor said that he should “go back to [his] country too.”

When the train finally arrived, the aggressor sat right across from Tsui and glared at him the entire ride, mouthing, “I’m watching you.” Throughout the ride, Tsui debated whether he should get off the train to escape but feared the man would follow him without anyone else to bear witness to what might happen.

Tsui says the current antiracism movements are important, but the U.S. has a long way to go to achieve true equality. “One thing’s for sure, it’s definitely not an overnight thing—I am skeptical that people can be suddenly woke after reading a few books off the recommended book lists,” he says.“Let’s be honest, before George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, there were many more. Black people have been calling out in pain and calling for help for a very long time.”

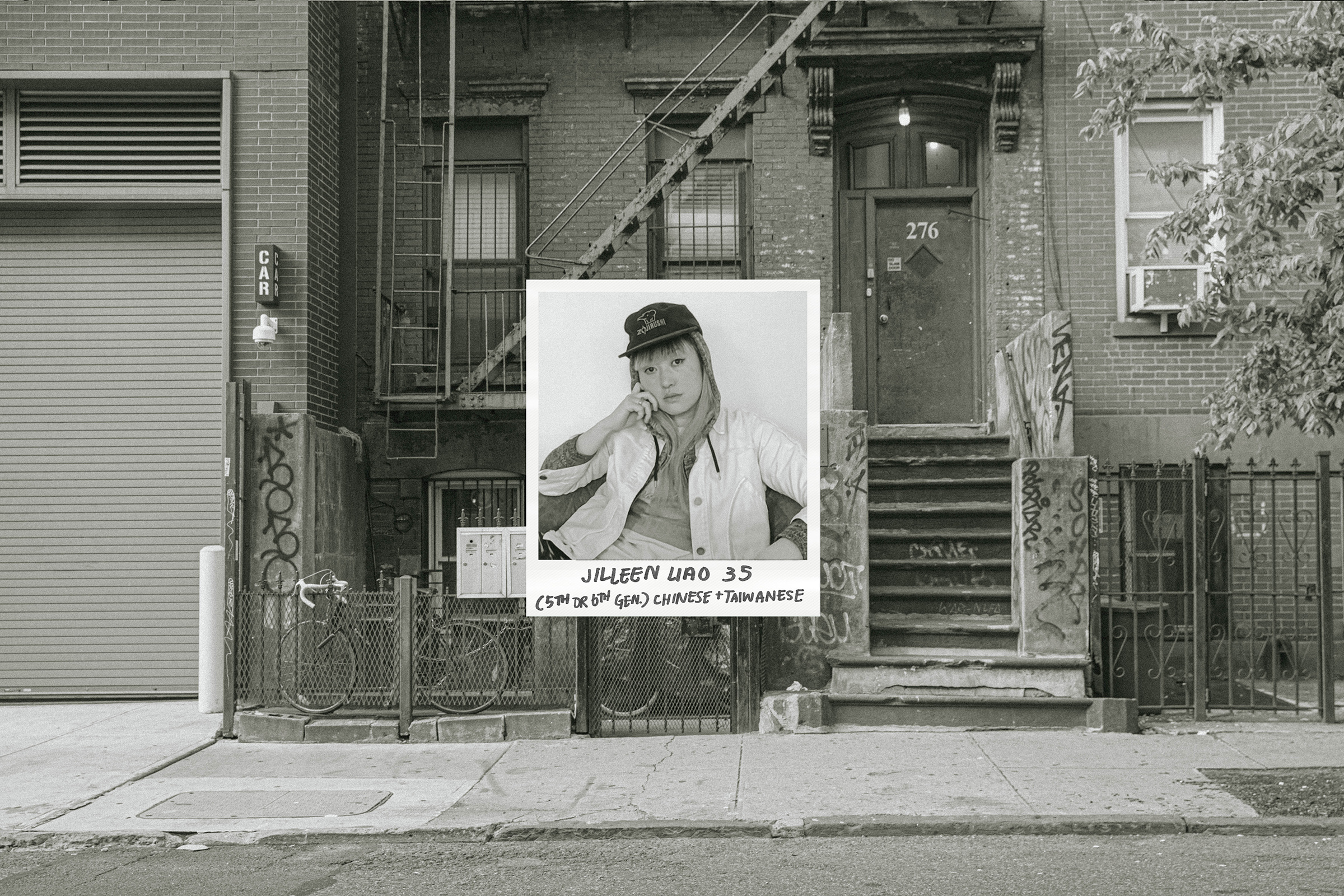

Jilleen Liao

Liao was on a grocery run on April 19 when she stopped to adjust her mask. A tall older man in a Yankees cap crossed the road toward her and walked in her direction. “Next time, don’t bring your diseases back from your country,” he told her.

“He was so close I could see the lines and wrinkles on his face,” says Liao. Frightened, she waited until he was several yards away to correct him and say, “I’m American, sir. Have a nice day!” At the time, Liao was carrying four grocery bags. Now she makes multiple grocery trips a week out of fear that carrying too many bags could put her in a position where she couldn’t defend herself. She also rides her skateboard to create more distance between herself and other pedestrians.

“Scapegoating is both a timeless and universal tool, so we shouldn’t be surprised COVID-19 racism is coinciding with an election year,” she says. “Especially as marginalized people, we can’t be afraid to speak out about our experiences. I believe community building starts with relationship building—however messy or imperfect that process might look. The Black Lives Matter movement continues to show us a new world is possible.”

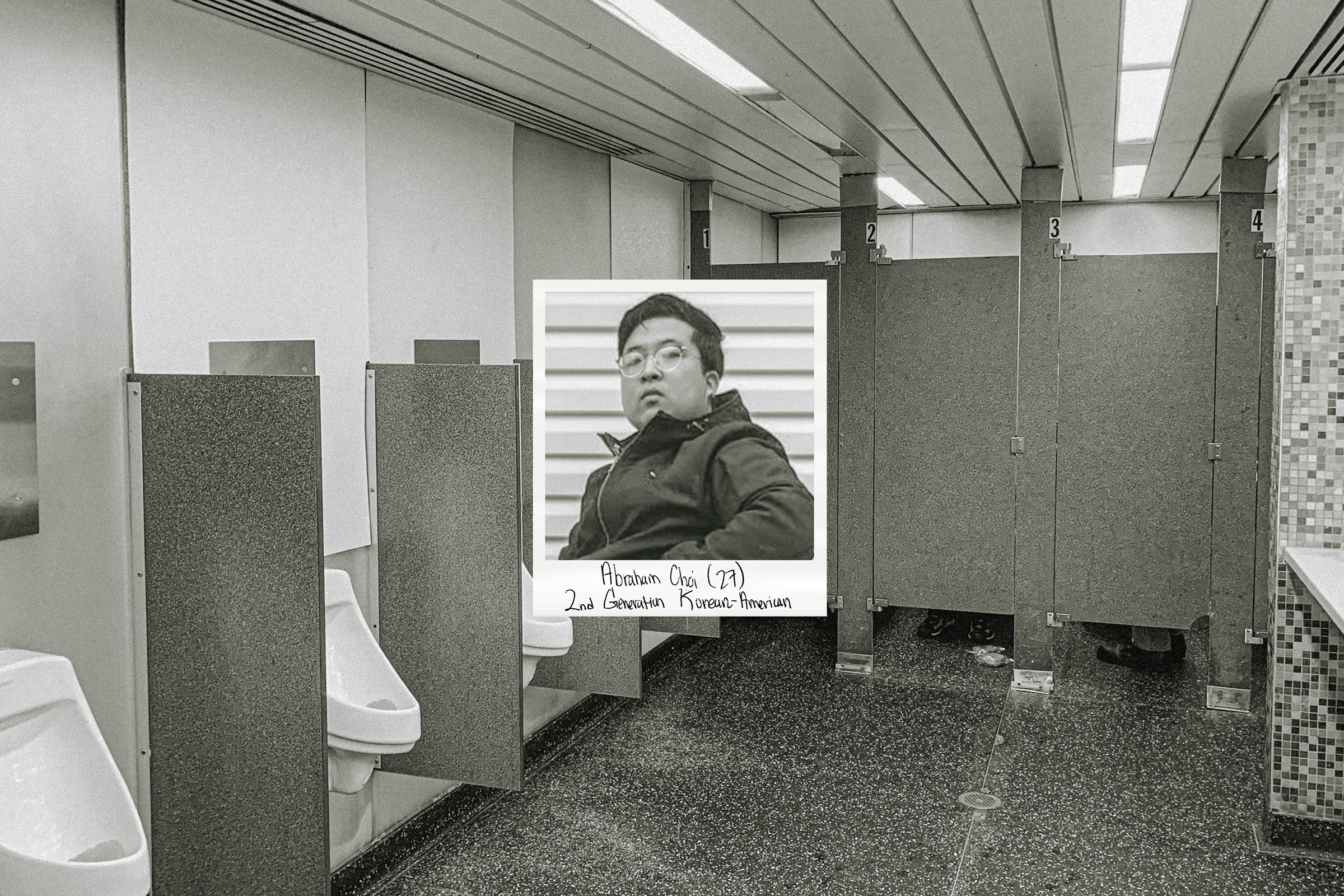

Abraham Choi

Choi was in a Penn Station bathroom on March 13 when a man stood behind him and started coughing and spitting on him. “I was shocked more than angry,” Choi says. “ Why would he do that?”

“You Chinese f-ck,” the man said. “All of you should die, and all of you have the Chinese virus.” Choi waited for the man to leave and then reported the situation to a police officer. “I was told that spitting wasn’t a crime, and that it wouldn’t be worth the paperwork I would have to go through to take any sort of action,” he says. Not knowing what else to do, Choi later anonymously recounted the story on Reddit, but he was hesitant to come forward in fear that his family might become the target of future attacks. Because of the shame he felt from the incident, he didn’t even share the story with his parents. But when attacks against Asian Americans kept occurring, Choi felt that he needed to speak up. “This whole thing made me into more of an introvert. I’m worried about my kid. I don’t want her to face this kind of racism,” he says. “It should just be love that we hold for one another.”

Choi says the events of recent weeks have made him more passionate about fighting racism than ever before. “I will not stand silent until everyone in the U.S. can be considered equal.”

Ida Chen

“Hey, Ms. Lee, I’d be into you if you didn’t carry the virus,” a man called after Chen on March 30. Chen told him off, but he turned his bike around and followed her for three blocks, shouting to her that “no one is into ‘ching chongs’ anyway” and that “this is why Asian men beat their wives.”

Afraid she would be in physical danger, Chen dialed 911 and put the phone on speaker, sharing her exact location and the details of the situation. The dispatcher said that they would send someone to look for the man, who disappeared, but she was never contacted again.

Since then, Chen has been doing everything she can to avoid similar situations. “The other day, I walked 40 blocks to avoid taking the bus or the subway. I’d rather be out in the open where I can run away if I have to,” she says. “I wear big sunglasses, and my hair is ombré blond, so I wear a hat to cover the black hair so you can only see the blond.”

In recent weeks, Chen says older family members have told her not to involve herself in “Black-white battles.” But, she explains, “In my opinion, oppression of one minority group results in oppression of all minority groups eventually.”

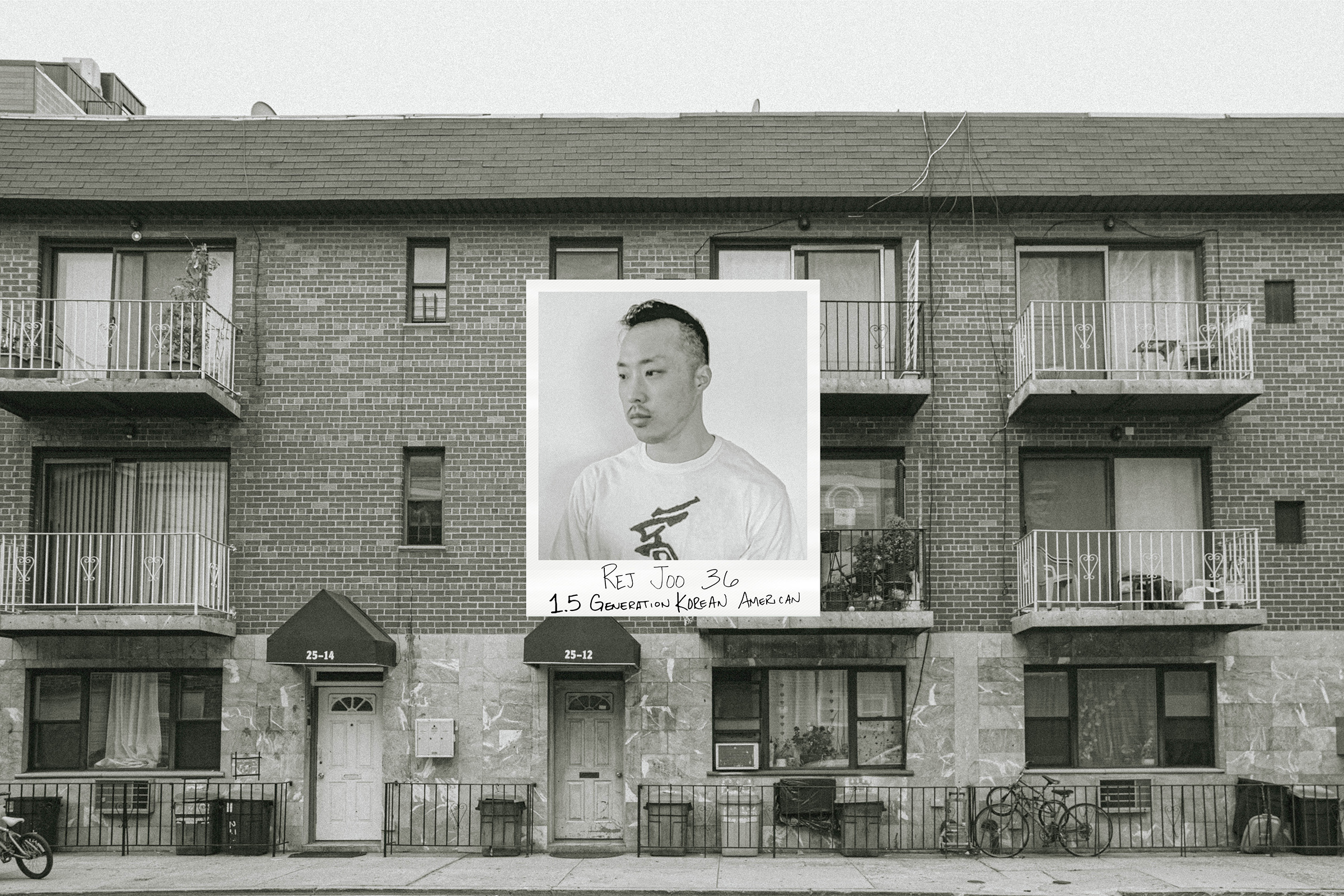

Rej Joo

Joo was on his way to the post office when a Latino man wearing a cap labeled PUERTO RICO mumbled, “Chinese,” at him. Joo turned around, and the man continued: “I was gonna see if you were Chinese. I was gonna put on my mask if you were Chinese.”

“First of all, I’m not Chinese,” Joo responded. “Second, you should wear a mask anyway. Do you understand how ignorant you sound? You’re a man of color, and it’s gotta be hard for you during this time. Why do you want to cause other people stress too?”

The man said he was sorry, that it was his mistake. Joo attributes being able to get an apology to his work as a program manager at the Center for Anti-Violence Education.“We’ve been helping people come up with strategies to intervene when they witness or experience hate-based violence or harassment,” says Joo.

Joo says it wasn’t the first time he’d heard racist comments from other men of color. “When you’re lashing out at each other, you don’t see the big picture,” he explains. Still, he hasn’t thought much about the incident lately. “The increased level of attention given to anti-Blackness is a must and a critical part of working toward eradicating racism overall,” he says.

Haruka Sakaguchi

Before Sakaguchi started this photo project, she was waiting in line to enter a grocery store on March 21 when a man came up behind her, hovering and making her feel uncomfortable. She politely asked him for some space, to which he responded, “What’d you say to me, chink?” He then proceeded to cut in front of her.

“Before the Black Lives Matter protests, I had contextualized my incident as an act of aggression by a single individual—a ‘bad apple,’ so to speak,” she says. “But after witnessing the unfolding of the antiracism movements and encountering heated debates between police abolitionists and those who cling to the ‘few bad apples’ theory, I came to realize that I too had internalized the ‘bad apple’ narrative. I gave my aggressor—an elderly white man—the benefit of the doubt.

“As an immigrant, I have been so thoroughly conditioned to think that white Americans are individuals that I wrote him into an imagined narrative in a protagonist role, even while he had so vehemently denied me of my own individuality by calling me a ‘chink.’ The protests have brought public attention to the idea that individuality is a luxury afforded to a privileged class, no matter how reckless their behavior or how consequential their actions.”

Jay Koo

“I wondered if I should’ve given my girlfriend an extra kiss before I left that night, if I should’ve spent more time with my brother,” says Koo, who was followed by two men after dropping off his brother at the emergency room at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital on March 24. The men called him racial slurs and yelled, “You got the virus. We have to kill you.” Wanting to appear strong and confident, he turned around and moved his book bag in front in case he needed to defend himself. “Unfortunately, Asians are often targeted for violent attacks because Asians are stereotyped as weak and nonconfrontational,” he says. He escaped by fake-coughing and saying, “I just got back from the ER. You want this virus?”

Friends and family have asked him the races of the men who confronted him, but he says it doesn’t matter. “The men acted out of reflex in quoting President Donald Trump and stated that I have the ‘Chinese virus,’ which propped up the Chinese as the scapegoat.”

Koo turned to history to process the incident. “I was reminded that the recent attacks against Asian-American communities due to COVID and the murder of George Floyd are connected and rooted in racist histories,” he says. “We can never truly be free unless we are all free, or as Dr. King states, ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’”

Hannah Hwang

“I don’t want to speak to you. You’re Chinese. Please get me somebody else to work with,” a customer told Hwang, an essential employee at a bank. The social-distancing measures put in place, including a window by the entrance so customers don’t have to step fully inside, have at times magnified the racism she has faced. “I’ve felt like a zoo animal, having glass separating us while they’re pointing and yelling at me,” says Hwang, who asked that her exact location not be shown because of privacy concerns.

As the wave of Black Lives Matter protests began, she initially felt guilty about focusing on what she had personally endured. “I can handle racially charged slurs thrown at me. Yet that only led me to acknowledge that my experience is not in any way less valid,” she says. “Instead, I pivoted my mentality in acknowledging my privilege and recognizing the critical role Asian Americans play in standing in solidarity with the Black community.”

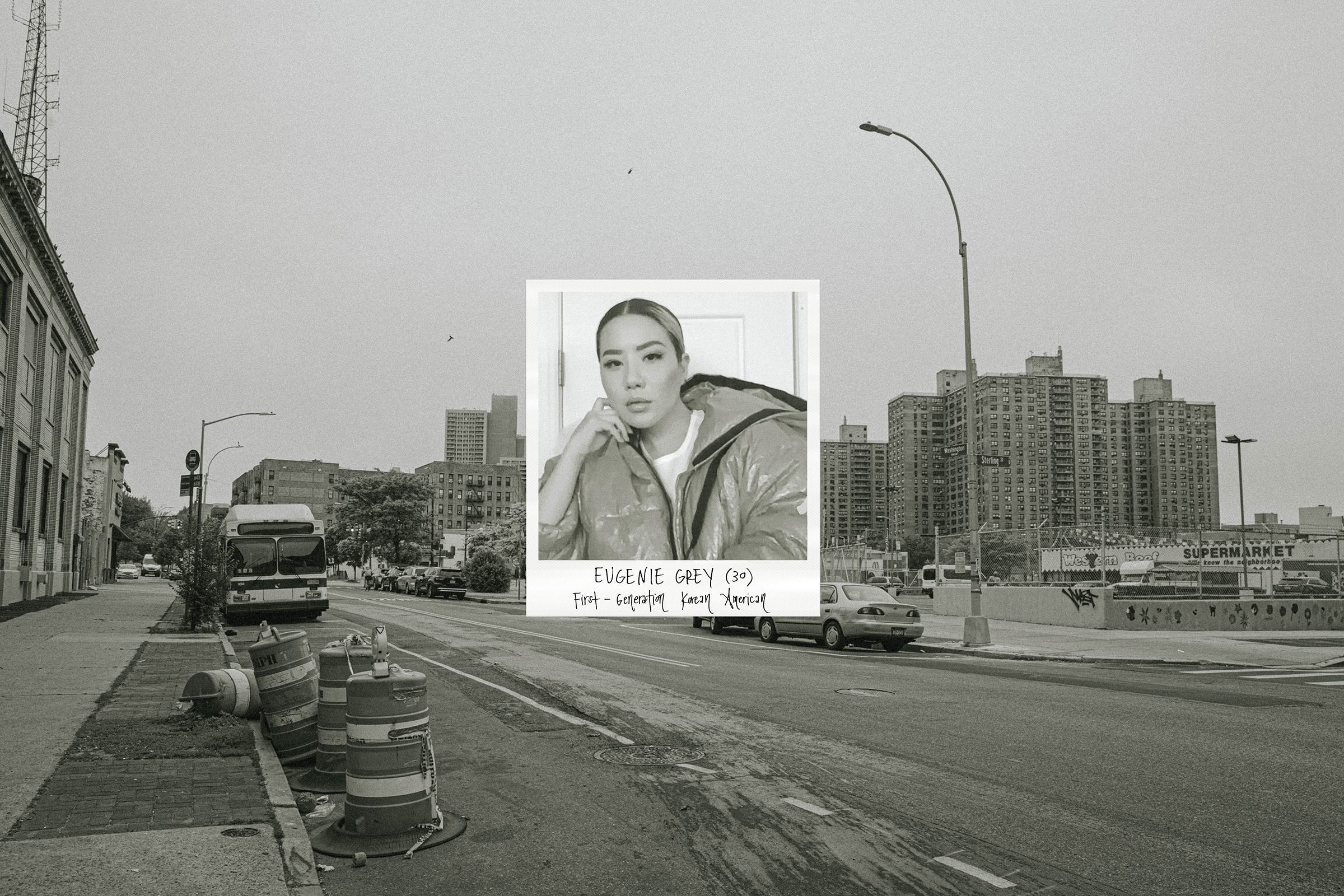

Eugenie Grey

Grey was out walking her dog on March 17 when she was body-slammed by a stranger. The aggressor also kicked Grey’s dog, which howled in pain. In the moments before the attack, Grey was bent over, picking up her dog’s waste, and her hood fell over her head. She couldn’t see the stranger approaching and was already in a vulnerable position.

Grey was the only one on the block wearing a mask at the time, and her eyes were visible above it—“That’s probably what immediately identified me as Asian to them,” she says. Later, she shared the incident on Instagram, using her platform to spark conversation and bring awareness to the issue. “In my last post about the racism I’ve experienced during this virus hysteria, I expressed gratitude that at least I wasn’t assaulted. I guess I can’t claim that anymore,” wrote Grey, who urged her nearly 400,000 followers to “take the time to be extra empathetic and kind to strangers to hopefully make up for their treatment from the rest of the world.”

“As horrifying, triggering and deplorable as what happened to me was, it was the one and only time I actually felt like there could be bodily harm inflicted on me,” she says. “Some people live in fear of that all the time.”

Douglas Kim

In early April, Kim opened an Instagram direct message from a concerned customer. It was an image of his West Village restaurant, Jeju Noodle Bar, the first noodle restaurant in the U.S. to achieve Michelin-star status. The words “Stop eating dogs” were scrawled in Sharpie across the eatery’s windowpane. Disheartened, Kim went in the next day and scrubbed it off.

Even before then, Jeju Noodle Bar was closed not just for dine-in customers, but also for takeout and delivery because of concern for employee safety. “Our employees were scared,” says Kim. “They were worried about using public transportation, not because they were scared of getting the virus but because they were getting awful looks from strangers and hearing the other stories.”

Kim says there’s a common thread between what happened at his restaurant and the incidents of police brutality around the U.S. that have led to ongoing protests and calls for change.“When you look at the larger picture, it all comes from one thing: racism,” he says. “As human beings, we should all be united. We should be all together. It’s good that we are trying to get together and fix things. Asian people coming together with Black Lives Matter protests.”

With reporting by Sangsuk Sylvia Kang

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Anna Purna Kambhampaty at Anna.kambhampaty@time.com