Marcus-David Peters had just left his day job teaching high school biology and arrived at his second job at a hotel, where he worked as a part-time security guard, when he apparently experienced a psychiatric episode.

He left the hotel naked, got into his car, then veered off the side of a highway in Richmond, Va. A police officer, Michael Nyantakyi, who had seen the vehicle crash, saw Peters climb out, and attempted to subdue him with his Taser. When Peters advanced, Nyantakyi fired two shots into the belly of the unarmed, unclothed 24-year-old, killing him.

Peters had no criminal record, his family said he had no history of mental illness or drug use, and his death, like those of many killed by police around the country, left his friends and family in anguish. “People ask me all the time, ‘What do you think caused him to have a mental break?’ And I say, ‘We’ll never know, because he was killed,’” says Peters’ sister, Princess Blanding. “It was easier to take out the threat, which was his brown skin, than to try to help him.” Richmond’s top prosecutor later concluded that the May 2018 shooting was justified.

There is no reliable national database tracking how many people with disabilities, or who are experiencing episodes of mental illness, are shot by police each year, but studies show that the numbers are substantial—likely between one-third and one-half of total police killings. And in the renewed national debate over racial injustice sparked by George Floyd’s killing at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer in May, those deaths should loom large.

Advocates for both racial justice and disability rights say Black Americans are especially at risk. Due to a host of social, economic and environmental factors, Black people are more likely than white people to have chronic health conditions, more likely to struggle when accessing mental-health care and less likely to receive formal diagnoses for a range of disabilities. By dint of how others react to their complexion, they are also nearly three times as likely as white people to be killed by police. The combination of disability and skin color amounts to a double bind, says Talila A. Lewis, a community lawyer and volunteer director of Helping Educate to Advance the Rights of Deaf Communities (HEARD). The U.S. government, Lewis explains, uses “constructed ideas about disability, delinquency and dependency, intertwined with constructed ideas about race to classify and criminalize people.”

The danger for people with mental illnesses and other disabilities is also born of police departments’ “compliance culture,” says Haben Girma, another lawyer and activist. “Anyone who immediately doesn’t comply, the police move on to force,” she says. The approach doesn’t work when police interact with someone who doesn’t react in the way they expect. Girma, who is both Black and deaf-blind, says that for her, the danger is hardly abstract. “Someone might be yelling for me to do something and I don’t hear. And then they assume that I’m a threat,” she says.

To address the problem, advocates promote a range of remedies—many dovetailing with the nascent national movement to rethink public safety. They want to decrease the total interactions police officers have with disabled people, redirect funds to other support services, and rethink law-enforcement systems and protocols to better protect people. The demands lend specificity and substance to the protest cries to “defund the police,” drawing attention to the tragedies that follow when armed first responders encounter a situation that demands not enforcement or coercion but care.

Some departments are trying. In recent years, police agencies around the country have offered their forces crisis-intervention trainings, which are designed to help officers safely and calmly interact with people with disabilities and de-escalate confrontations with the mentally ill. But the quality of these training programs is all over the board, and the priority remains elsewhere. A 2016 report from the Police Executive Research Forum found that nationwide, police academies spend a median of 58 hours on firearm training and just eight hours on de-escalation or crisis intervention.

In 2015, the Arc, one of the country’s largest disability-rights organizations, launched its own program to teach law-enforcement officers, lawyers, victim-services providers and other criminal-justice professionals how to identify, interact with and accommodate people with disabilities. “We’re talking about having a community really understand each other, and what that can look like,” says Leigh Ann Davis, who leads the Arc’s National Center on Criminal Justice and Disability. The program has now trained 2,000 people in 14 states.

But training programs, regardless of quality, are not enough, activists say. As protests continue nationwide and demands to defund or abolish the police gain steam, some advocates are pushing for more radical models that seek to avoid bringing people with disabilities, or those experiencing mental-health crises, into contact with the police.

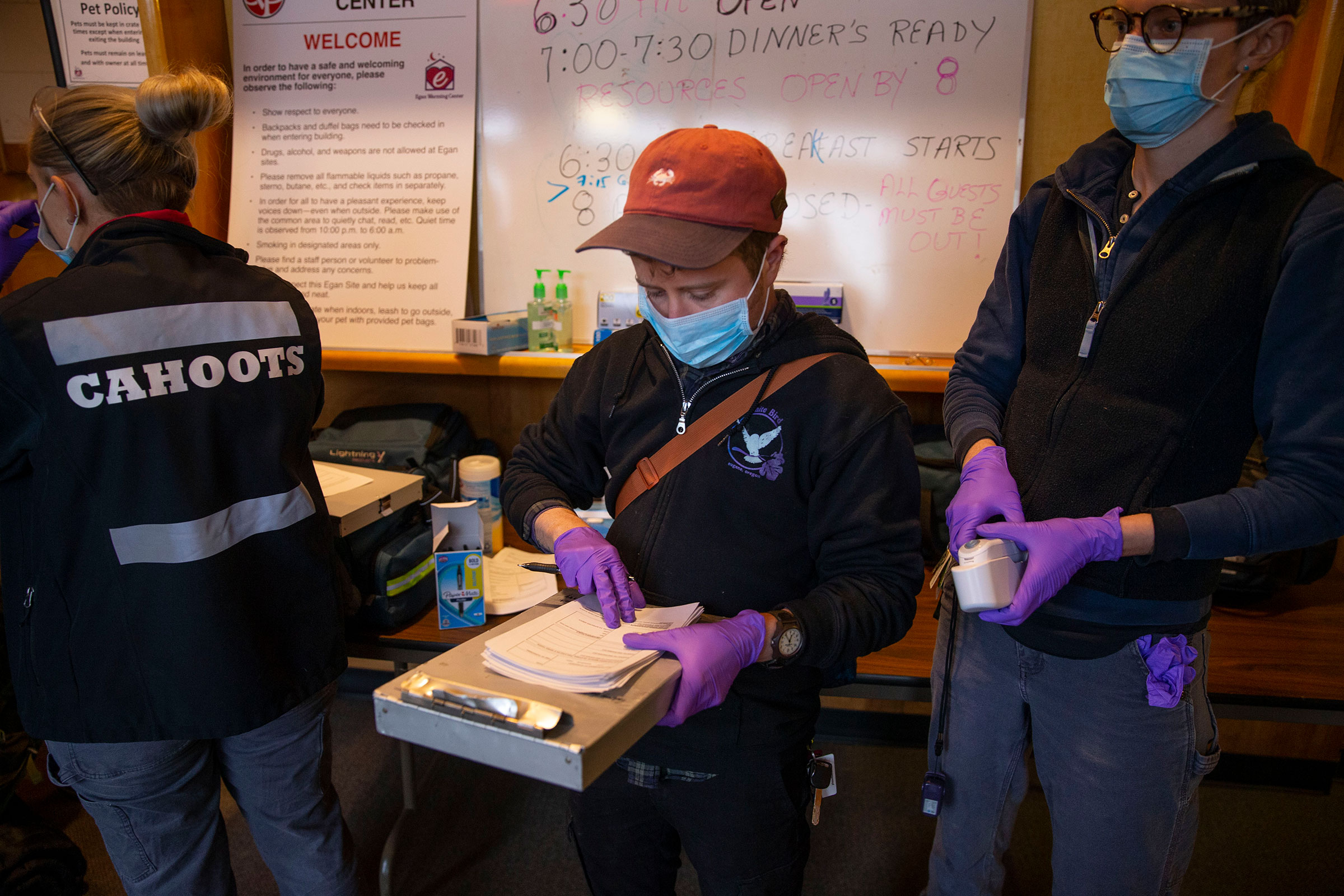

In Eugene, Ore., for example, the White Bird Clinic runs what’s known as CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets), a program that reroutes 911 and non-emergency calls relating to mental health, substance use or homelessness to a team of medics and crisis-care workers. Those teams respond to such calls instead of—not alongside—police. The CAHOOTS program, which launched in the late ’80s, receives roughly 24,000 calls each year; 17% of Eugene police calls are redirected to CAHOOTS, a boon to police departments, which can better use resources combatting crimes.

Police unions have criticized CAHOOTS and similar programs on the grounds that it’s dangerous for medics and crisis-care workers to respond to calls without armed officers. But Tim Black, the CAHOOTS operations coordinator, says that’s mostly not the case. His teams work closely with the Eugene police department, and last year, just 150 of the 24,000 calls directed to CAHOOTS required police backup.

“There’s a really constructive relationship that we have with law enforcement because they see us as the expert,” Black says. “They trust us to engage in all sorts of situations that they’re not equipped to handle. But they also trust us to provide them with feedback and oversight when we see things that aren’t going well because they know that it’s coming from the place of understanding.”

Olympia, Wash.; Denver; and Oakland, Calif., have developed programs modeled after CAHOOTS, and Black says other cities are beginning to call for advice too. In New York City, a coalition of civil rights and social-service organizations has proposed a pilot program for two precincts in which EMTs and crisis counselors would respond to mental-health calls instead of police. The coalition wants to devote $16.5 million to the pilot over five years. (New York spends nearly $11 billion on police-related costs each year.)

“A police response is not the kind of response you want when people are in a mental-health crisis,” says Carla Rabinowitz, advocacy coordinator for the mental-health nonprofit Community Access and the coalition’s project leader. She notes that at least 17 New Yorkers experiencing mental-health crises were killed or injured by police in the past five years. “It’s much better to have a peer and an EMT who can talk to the person, figure out what is going on in the person’s life, offer them resources.”

Racial equality and disability rights advocates are demanding change beyond law enforcement. Police violence, after all, is only part of why Black Americans have overall worse health outcomes and shorter life expectancies than white Americans. Due to years of systemic racism, Black Americans are more likely than white Americans to have lower incomes, and to live in less safe neighborhoods with fewer grocery stores, fewer parks, worse air quality, and less desirable schools. These factors not only contribute to higher instances of physical ailments, like asthma and diabetes, they’re also intrinsically intertwined with worse mental health outcomes. Black Americans are more likely to have schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder.

These challenges are compounded by many Black Americans’ lack of access to unbiased medical and mental health care. Black Americans are less likely than their white counterparts to be identified as having autism and learning disabilities.

Even talking about disability and mental health in the Black community can require adopting a language separate from mainstream medical culture. “Disability is commonly understood through a white and wealth privileged lens,” says Lewis, the lawyer with HEARD, who helps disabled people facing violence and incarceration across the country. Lewis explains that government officials and even mainstream disability rights leaders often rely on formal definitions of disability that can lead them to overlook the experiences of disabled Black people.

Many Black Americans grow up experiencing police violence, witnessing it in their communities, and seeing videos of deaths as a matter of course. But due to the ways the U.S. medical and education systems have created distrust among communities of color, advocates say there can also be stigma and a lack of awareness about disability in Black communities, even as they push back against violence that impacts these vulnerable populations.

Teighlor McGee, a 22-year-old who has been gathering personal protective equipment and sending medics to help protesters in Minneapolis, says that racial justice groups often don’t think about disabled people when holding demonstrations or advocating for change. “A lot of people don’t see disabled people as people,” she says. “People can’t picture disabled people facing police brutality and violence because they can’t picture disabled people going places.” McGee noticed the lack of spaces to connect with others who shared her experience as a Black autistic woman, so she started the Black Disability Collective online to fill the void.

When people with disabilities or mental illness are not at the center of the conversation, activists say that makes it harder to build understanding and make change. Adrienne Bryant in Tempe, Ariz., says she witnessed the limits of police understanding this year. In January, she called the police because her 29-year-old son Randy Evans, who had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia last year, was experiencing a manic episode and she needed help getting him to a mental health facility. But when police showed up at her apartment with riot shields and rifles, she and her younger son panicked, the officers were yelling, and the situation quickly escalated.

“I said several times, ‘Please do not kill my son,’” Bryant recalled, near tears. “One wrong move and I could have lost two sons that night.”

The police dispatcher had given the responding officers an incorrect name, which turned out to belong to a felony offender who was wanted for violating probation. The dispatcher also told officers that the man they were responding to had knives. (In reality, Bryant and her younger son had collected and hidden all of the knives in the house to keep them away from Evans until police arrived.) As a result of these mistakes, the responding officers believed they were confronting an armed felon, rather than just performing a mental health call. Tempe Police Chief Sylvia Moir told TIME that the responding officers said the mistaken name did not change their behavior. The department believes they responded appropriately in this situation. “We have to first start with, are the police the right societal actor to be inserted into this space and into this societal issue?” Moir says.

More than 60% of Tempe police officers are trained in crisis response, Moir says, and the city has a separate crisis response team that can also be called in to help in situations such as mental health crises, sexual assaults and domestic violence incidents. But she said that she would be worried about sending a crisis response team without police officers carrying lethal weapons in case situations turned dangerous. “I think this is reflective of the police really being the reflective muscle of the government and that there is nobody else out in this space doing this work in this kind of very complex and volatile space,” Moir says.

But Bryant says the damage has been done. Her younger son remains traumatized by the incident; he avoided leaving the house for months afterward. And she is still working to ensure Randy’s name is not associated with the incorrect one provided by the dispatcher. “We will never call the police again,” she says.

Meanwhile, in Richmond, Blanding, whose brother Peters was killed near his car, is using the current, galvanizing prominence of race and criminal justice to push the reforms she has been seeking since his death. Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney recently released a plan “for re-imagining public safety” in the city that includes a civilian review board and a version of the family’s idea for a crisis alert that would involve mental-health experts responding to a mental- or behavioral-health crisis, in addition to other policy changes.

Blanding says she is glad to see progress, but won’t celebrate until the city implements a system that ensures “having a mental-health crisis does not become a death sentence.”

This appears in the July 06, 2020 issue of TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com