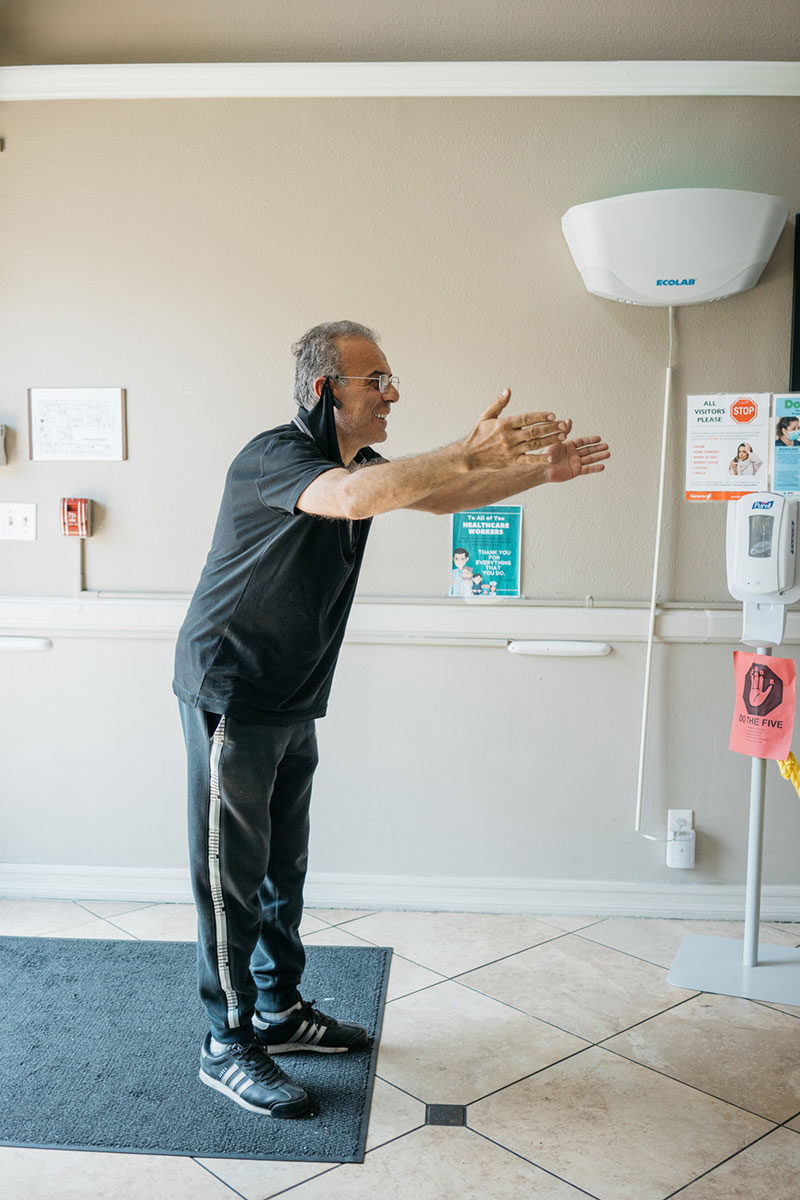

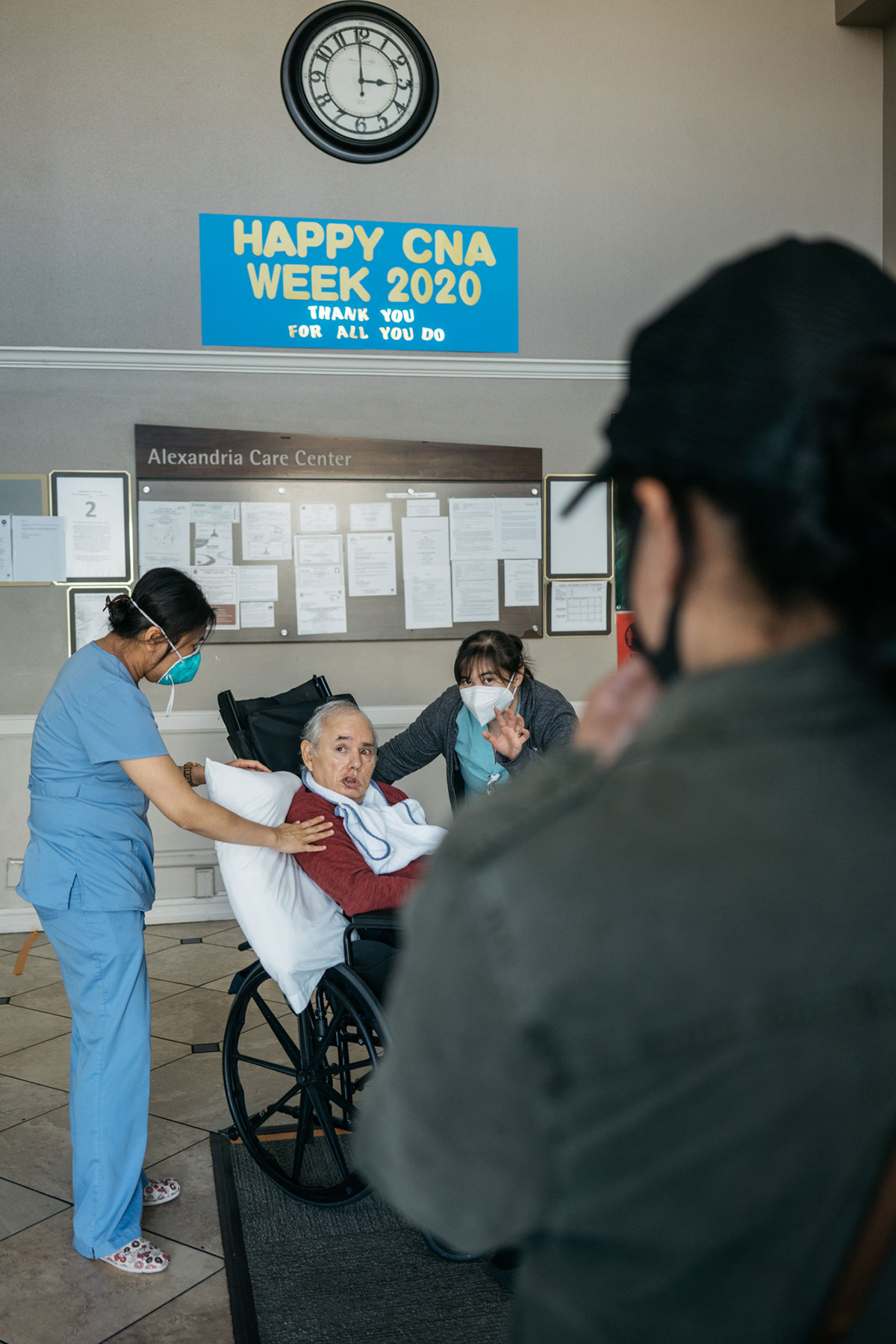

Father’s Day marks the second time since the pandemic began that Alexandria Care Center, a nursing facility located in Los Angeles, Calif., has held open their sliding door for parents and their children to see each other from a distance. Last month, Alexandria Care Center allowed children to see their mothers at a distance for Mother’s Day. This Sunday, nurses wheel fathers down a corridor to the lobby where they see their children and grandchildren standing at the doorway.

Beginning June 18, Los Angeles County relaxed restrictions on nursing homes, allowing visitations with masks on and six feet of space. However, inside visits are not allowed in nursing homes unless four weeks have passed since a positive coronavirus case at a facility. At Alexandria Care Center, COVID-19 patients are housed in a separate unit with their own designated staff members. According to the California Department of Public Health data last updated on June 9, Alexandria Care Center has had 23 COVID-19-related resident deaths. “No one ever thought that they or their loved ones would ever have to deal with a worldwide pandemic,” says Lori Mayer, Vice President of Communications for Genesis Healthcare, which operates Alexandria and 500 other nursing home facilities across the U.S. “California has not eased restrictions yet. In the meantime, we are happy to facilitate engagement of our residents and their loved ones visually through a window or door.”

This Father’s Day, in compliance with those rules, locked eyes had to take the place of hugs with dad. Salutations and words of affection are spoken at an elevated tone to be heard over phone rings, the air conditioning and the sounds of nearby Sunset Boulevard. With a carpet separating them, children pass cards, a hot lunch and flowers to a staff member in Personal Protective Equipment who then sprays the items before handing them to the resident.

Armenuni Gregorian was notified last month that her father Landzhuni Oaanesyan, 81, had COVID-19. Landzhuni has been a resident of Alexandria Care Center since January. “I see him on FaceTime, but I cannot really see his face,” says Armenuni. Armenuni had intended to take her father back to her home where he used to reside, but then learned he had contracted the virus. Landzhuni has since recovered from COVID-19. A socially distanced Father’s Day event at Alexandria Care Center will provide Armenuni and Landzhuni the first time to be face to face since February. “I don’t know if he’s OK or not,” says Armenuni, but she feels that seeing her father herself will bring her some ease.

Hong Park, 63, and his son, Tristan, have not seen each other since early March other than via Skype. On the first call, Hong reassured Tristan, saying, “Don’t worry about me. I’m fine.” Before the pandemic, Tristan visited his father twice a week. Hong does not like when others touch him, so Tristan wanted to give his father a shave and a haircut on Father’s Day. But, due to social distancing guidelines that include no physical contact, the grooming will have to wait.

“It’s Father’s Day and I want him to know that I care,” says Jacqueline Medina whose father, Gilbert Medina, 63, has been a resident at Alexandria for a year. Jacqueline Medina has not seen her father since a few days before the lockdown on May 12. She is able to do FaceTime visits, but her father is non-verbal as a result of a cerebral hemorrhage. “My biggest fear was that he wouldn’t understand why I’m not there. Hopefully now, he’s starting to get the picture that something out of my control is wrong,” says Jacqueline. Most of Gilbert’s interactions with his daughter involve her looking at him virtually and hearing her voice. Jacqueline’s mother and Gilbert’s ex-wife is a director of nursing at another long-term care facility. “It’s super important that the family is there as much as possible…”

At the beginning of the stay-at-home order, Jacqueline repeatedly called the California Department of Public Health and Genesis Healthcare to ensure quality of care. “In the beginning, I was flipping out.” Jacqueline is used to visiting her father daily. “It’s probably single most difficult thing about all of this. I can deal with my job situation being unstable and everything else but not being able to see my dad has been devastating.”

The next time these families will connect again, and at what level of intimacy, is unknown. Daily visits where children can assist in bathing, feeding or pushing their father’s wheelchair still feels distant. For now, they await updates from the facility’s administration and place their trust in the certified nurse’s assistants who care for their parents’ needs. “At some point, I had to surrender because there is not a whole lot I can do,” says Jacqueline Medina.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com