My father was not quite 20 years old in the fall of 1937 when he set out on a thousand-mile trek across China. He didn’t do this on his own, but rather with staff and students from the evacuated Nanjing University—and his school wasn’t unique in doing this, either. Across China, students, professors and staff crammed as much as they could into carts, wheelbarrows and their own backpacks. They packed up supplies, books, lab equipment and machinery. Some even brought along valuable imported livestock from animal husbandry programs.

Japan and China had entered the Second Sino-Japanese war, and cities in eastern China were in danger of attack. In 1937, China’s population stood at 500 million but only 43,000 were university students, a brain trust the Chinese government was desperate to protect. When universities were ordered to evacuate west, toward the relative safety of China’s interior, 77 abandoned their home campuses. It was an exodus unlike any other, yet it remains a chapter in history virtually unknown outside China.

Even less known is the tale of a singular journey that took place during this time to safeguard one of China’s greatest library treasures.

Before Wikipedia

In 1771, the 36th year of his reign, the Qianlong Emperor decreed the creation of an encyclopedia of classical Chinese literature, a work that would outshine a scholarly masterpiece from the preceding Ming dynasty, the massive Yongle Dadian encyclopedia. Named after the Yongle Emperor and completed in 1407, it had contained 370 million words, the largest encyclopedia in the world.

The Imperial libraries already owned vast collections of literature to draw from, yet the emperor asked for contributions from private libraries. The Qing dynasty’s Manchu rulers, conscious that the Han Chinese population considered them foreign usurpers, had conducted several literary inquisitions over the decades, burning books with anti-Manchu sentiments and punishing their owners. So when the encyclopedia project began, the empire’s Han Chinese subjects were understandably reluctant to respond. The emperor then issued decrees that all books donated to the effort would be returned and their owners immune from penalties even if their books contained “Evil Words.” After this, more than 10,000 books were handed in.

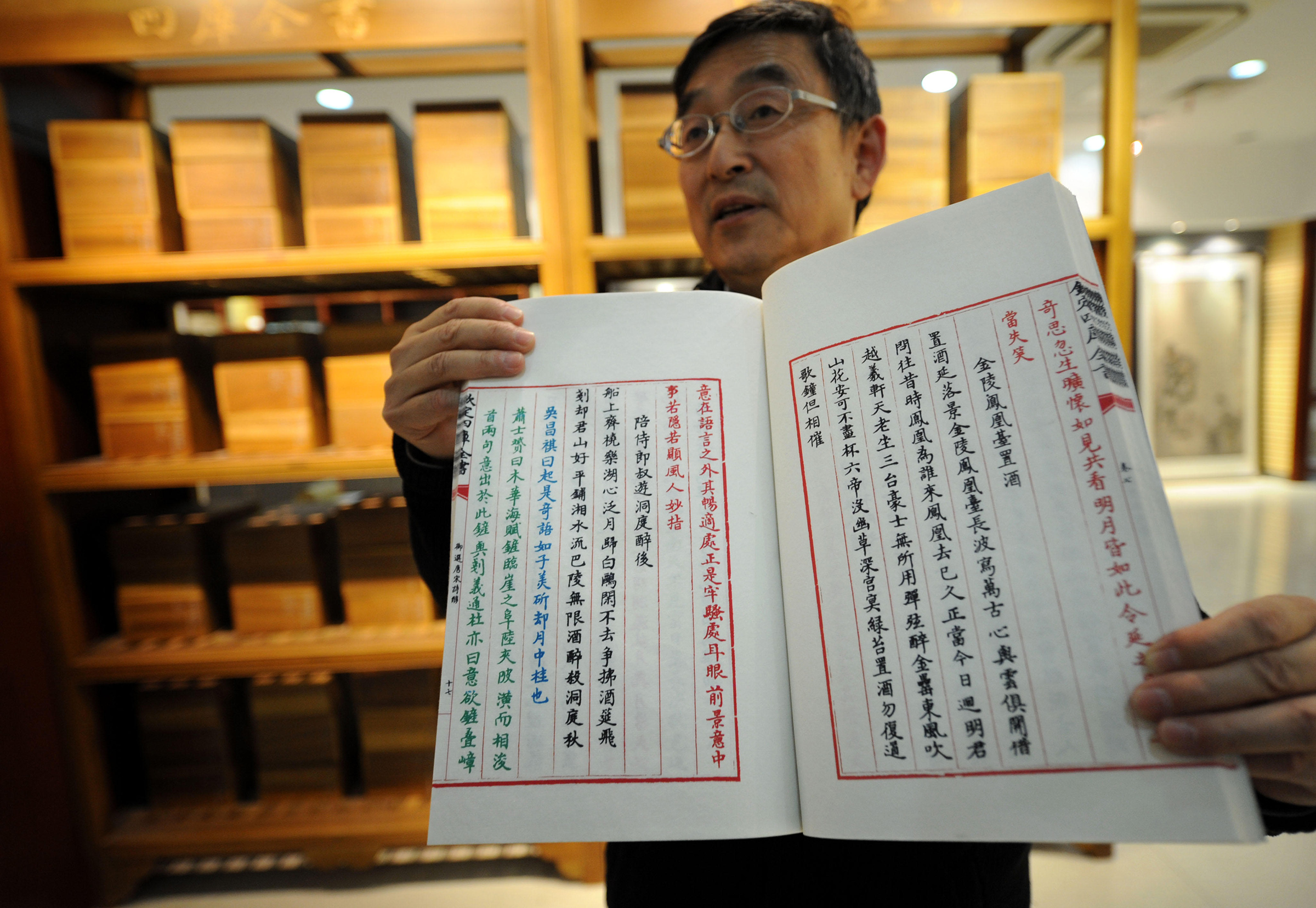

A decade later, in 1782, the Siku Quanshu—which can be roughly translated as Complete Library of Four Branches of Literature—was complete. It comprised 35,381 volumes and approximately 800 million characters. It would be 225 years before another encyclopedia surpassed this number—in 2007 when English Wikipedia approached a billion words.

But after all that knowledge had been gathered into one place, the Qianlong Emperor reneged on his promise. His censors destroyed some 3,000 works for being anti-Manchu and their owners were executed.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Destruction and Restoration

Seven hand-copied sets of the Siku Quanshu went to seven specially built libraries: four for the emperor, located in four Imperial palaces, and three for public use. One of the three was the Wenlan Ge library in the city of Hangzhou; the collection became known as the Siku Quanshu Wenlan Ge.

The books were nearly lost when rebels stormed Hangzhou during the Taiping Rebellion in 1854. The Wenlan Ge was heavily damaged and its books stolen, some by looters, some by book lovers. Eight years later, a book collector named Ding noticed a shopkeeper at the market wrapping peanuts in paper cones made out of pages from a book. He realized they were pages from the Siku Quanshu. He and his brother, also a bibliophile, began tracking down lost volumes, buying back books when necessary, and re-copying missing sections. The project passed into the hands of Zhejiang Library, which by the 1920s succeeded in restoring all the volumes; today it is the most complete of the four surviving copies of the Siku Quanshu.

Traveling with a Priceless Library

As Zhejiang University in Hangzhou planned for evacuation, Chen Xunci, Head Librarian of Zhejiang Library, asked the university to take the valuable collection from the Wenlan Ge with them. The school chancellor agreed, even though it added another 230 boxes to their cargo.

Chen promised to get funding for the library’s transportation, but couldn’t persuade the education ministry to give him any, even as a loan. He borrowed from family and friends, and before the war ended, had sold his own property to ensure the Siku Quanshu’s safety.

Thus began the library’s journey. The university’s route diverged at times from that of the books, which they tried to move by boat or truck whenever possible; otherwise, they would pack the boxes into carts and wheelbarrows, and pay local laborers to move the books. At times the students carried some of the books in their backpacks. In one near-disaster, a container of books overturned while crossing a stream. The box was taken to the nearest town, where the books were spread out to dry in the wide courtyard of the local City God’s temple.

All the “schools in exile” faced danger and hardships. There was the endless trudging each day, under threat of aerial attacks. They were always tired, cold and hungry. They slept in temples when no other lodgings were available. Professors did what they could to continue classes if they stopped to rest for more than a few days. Cut off from their families, students had to make do with a small government stipend. My father recalls times when, rather than spend his money on fuel, he would take a tin can and poke around abandoned cooking fires to find remnants of coal.

Yet despite it all, they were generally cheerful, he said, because everyone was suffering the same hardships. They were touchingly optimistic, trusting their professors to bring them safely through a war zone.

And they were young. Memoirs by Zhejiang University students include accounts of unrequited love (young men outnumbered the women five to one), with many women complaining about the truly terrible love poems they received from admirers. When they were able to stay in one place for weeks or months, the students enjoyed outings and sports. In rural areas, women in short skirts and bathing costumes had never been seen and the female students caused a scandal.

It wasn’t until the New Year of 1940, after 1,400 miles on the road and 28 months of makeshift classrooms and dormitories, that the 800 members of Zhejiang University arrived at their final wartime campus in Zunyi, a small town in Guizhou province.

Yet with aerial attacks now moving deeper into China, the Siku Quanshu was still not safe. Guizhou is famed for its spectacular karst caves and the chancellor moved the books to a cave outside Zunyi. Two university servants stayed behind to guard and care for the books. The volumes survived the war in surprisingly good condition and were sent back to Zhejiang Library.

The story of the Siku Quanshu Wenlan Ge is inseparable from the story of people who risked all to protect a cultural legacy, from the librarian who sold off his house to the students who would not abandon the heavy boxes that slowed their travel.

As a final note, in 1994 a professor from Zhejiang University was in Kyoto looking through Japanese war records when he found a note dated after the fall of Hangzhou. It stated that “on February 22, 1938 the Occupied Area Literature Procurement Committee sent nine agents from Shanghai to Hangzhou to search for books from the Wenlan Ge.”

If the books had not been moved, the fate their keepers feared could have easily come to pass. But by the time Japanese agents reached Hangzhou, the Siku Quanshu was already on its long march to safety.

Janie Chang is the author of the novel The Library of Legends, available now from William Morrow. The Library of Legends draws from family history and is set during the evacuation of Chinese universities at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com