As the end of summer approaches, debates over schools re-opening in countries across the world have parents, teachers and authorities all facing difficult choices amid the coronavirus pandemic. Those decisions have also become part of what has become, in some places, a broader trend of urban flight: In New York City, for examples, some wealthy families have left Manhattan for good and plan to enroll their children in schools closer to their second homes in places like the Hamptons.

And the school decision is just one facet of the exodus. The pandemic’s early months were marked by high-profile incidents of people—including U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s top adviser—flouting travel and lockdown rules to get out of big cities, and more recent reports indicate significant increases in people looking to permanently move out of cities to the suburbs and more rural areas.

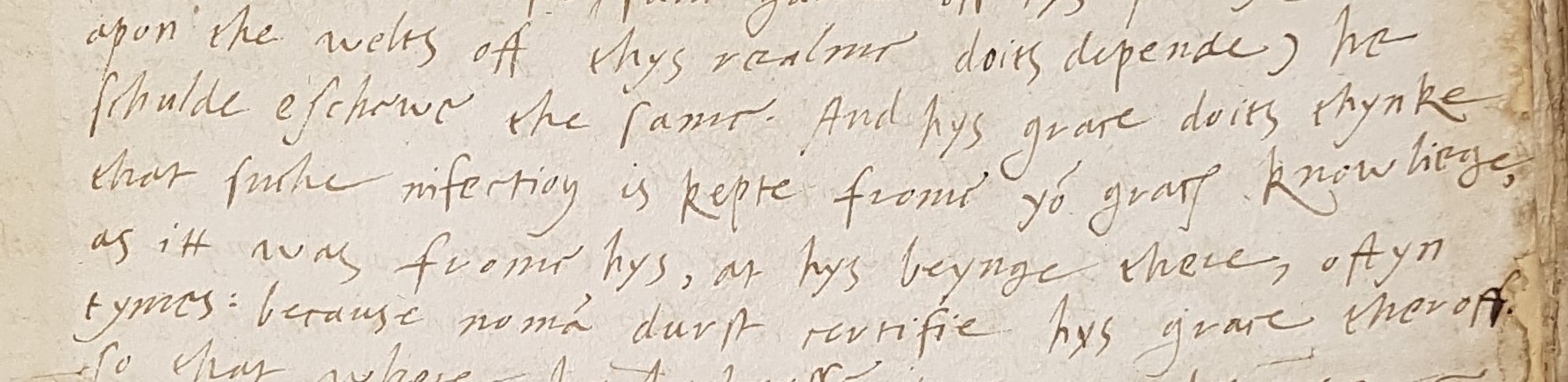

Yet 2020 is by no means the first time wealth has enabled mobility in a time of crisis. Euan Roger, principal medieval records specialist at the U.K.’s National Archives, researched quarantine methods in 16th century England under the reign of King Henry VIII and published a paper on the subject last year.

Reflecting back from 2020, he found some striking similarities with the king’s response to a plague epidemic of the early 1500s: the top tier of London nobility was able to leave the capital, so they did.

“Mobility is definitely the key way that if you can afford it, that’s what you do,” Roger, tells TIME, speaking about the Tudor context.

A young King Henry VIII was in his late 20s and at the start of his reign when an outbreak of the plague ravaged Europe in 1517 and 1518. Contemporaneous reports indicate his intense fear of contracting the disease, given that his grandmother was thought to have died from it in 1492. A report that Roger found dating to 1511, the same year that Henry’s first born son died in infancy, said that nearly two decades years later after his grandmother’s death, “the king [was] disturbed.”

“It shows there’s this fear that while he might be the king, and he might be rich, the plague can strike anyone in the royal family,” Roger tells TIME. “He talks a lot about how the health of the nation depends on his health. He’s saying that if he dies, the country could have serious problems.” Indeed, there was a real risk that Henry’s death without producing an heir could plunge the country back into civil war; the 32-year-long Wars of the Roses had only ended in 1487 and had also erupted from disputes over claims to the throne.

Early modern London in 1517 and 1518 was not a safe place to be. A nasty and mysterious “sweating sickness” was sweeping England. Throughout the epidemic, Henry and the royal court left London and constantly moved around to avoid infection, stopping at places for short periods of time before moving on to the next palace or residence. Hospitals as we know them now did not exist then, and there was no state or countrywide health network; each local area had their own set of customary laws and measures to tackle the outbreak. In addition, the idea of quarantine, which had already been used in Italian city-states by this time, was difficult to enforce in countries like England and France where government was much less centralized.

It was commonly believed that infection spread by contaminated air, and that the air needed to be avoided by moving around. “It’s a different way of thinking about disease, but actually the way that you counter miasmatic air is not that different to the way later generations would combat infection. It’s that belief in contamination,” says Roger.

Henry’s insistence on moving around was based on his fear of the disease spreading among his subjects and of eventually contracting it himself, as well as worry that leading officials in London were keeping infections secret from him. Roger says that at this time, outbreaks were very local, so only traveling a few miles was thought to help and keep the court safe. “There are different ideas about how fast the plague could move, but you’re essentially trying to outrun the spread of infection,” he says. “You have to have a second property, or be able to stay in the countryside. It is very much for the wealthy.”

There were some occasions that increased mobility did not satisfy Henry’s need to feel safe from the epidemic; records indicate that in August 1517, the King dismissed the entire court as the plague had made “great ravages in his household.”

And while the 16th century is a very different society from our own, there are some parallels that can be drawn with the idea of mobility. Densely populated streets, lack of outdoor spaces and crowded transport systems have made social distancing in cities during COVID-19 much harder. Some experts have also argued that fleeing a city in a time of crisis can be an instinctual reaction for those who have the means to do so; some have compared the urban flight of 2020 in New York City to a wave of moves out of the city in the aftermath of 9/11.

For Roger, whose research also looks at Tudor quarantine measures that could be classified as “social distancing” today, the current environment has made him think more about how authorities handled outbreaks in the 16th century.

“I’d always had academic questions about the practical mechanics, and how effective those measures have been,” he says. “That’s what I’ve been thinking about as we’ve had to manage in the present day.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com