Prone to depression to begin with, and living alone on an 80-acre farm, I have found myself fighting those dark dogs and thinking, on more than one occasion, that while we are trying to mitigate one pandemic, we may inadvertently be causing another. The times I have been out have seemed surreal, everyone’s face covered with masks, some black, some white and some fancy, with floral fabric and even lace trim, but that can’t change the fact that half of the human face has been eradicated by this virus, only the eyes visible. They say that the eyes are the windows to the soul, but COVID has taught me that this is untrue. The eyes tell part of the story, but the soul can be glimpsed only when one has access to the whole of the human face. Cut off from the curve of the lips, the regal or ski-sloped nose, the tell-tale dents of dimples and the road-map-like wrinkles that can form in later years, the eyes can seem almost slippery.

My farm is in Fitchburg, Mass., an old mill town that has seen better days. As warm weather arrives, Fitchburg usually opens its farmers’ market, which has a transformative effect. Suddenly the dull alleyways and cryptic roads begin to blossom as boxes of produce spill onto tables set up for selling. Not this year, though. COVID will keep that busy market closed until July. Meanwhile, in essential stores there are boxes made of blue masking tape indicating where you should stand, 6 ft. away from any other masked shopper, an acrylic sheet hung from the ceiling separating you from the people working the registers who take your money with a latex grip.

Sometimes I want to cry out, if only to hear how my sound might sever the silence that has descended seemingly everywhere, the river rushing at the edge of my land sounding preternaturally loud. This river runs in every season, and its noisy garble has come, for me, to represent the COVID-19 virus, a sound impossible to understand, a sound that permeates everything I do or think, a sound that blots out other, smaller sounds that could bring comfort, anything, really, the weeping of wind or the clop-clop of my horses’ hooves on the cement floor of my barn. Every place I go I hear that river; I hear it in my bedroom at night when I log on to my computer and look up the latest figures in my state with its rising death toll.

Walking through Walgreens, I sometimes long to rip the masks off the faces of those nearby, just to touch. This suggests to me that I am in a sorry state, my plate seeming empty, my mood dour. Before COVID I thought I had mastered the art of independent living. I chop my own wood. I grow my own food. I fix the engines of lawn tractors and mowers, mastering circuits and sparks. Now I know that my mastery was but an illusion. Now I know that aloneness is deeper and more fraught than anything I could have imagined. Quarantine. What a weird word. It puts me in mind of barred windows, of asylums, of bright tubercular blood on a white cloth.

Fact of the matter is, I have become depressed, living my COVID days. While my tolerance for aloneness is huge, it is no match for this virus and what it demands from us to stay safe. I never knew, until now, how truly important are the small gestures of goodwill one finds in a stranger’s smile, in the brushing of hands, in the clatter of commerce. Even my land, it seems, has succumbed. It is now green and lush, the snow no longer, but in moments of extreme isolation, when my mood shifts, as it often does, my fields bleach out, so that the world looks white, an endless expanse that frightens me because it can seem like color will never come back.

From the late 1950s to the 1960s, a psychologist by the name of Harry Harlow performed a spate of cruel but illuminating experiments on some of our closest mammalian cousins. He removed baby rhesus monkeys from their mothers and gave them two surrogate “monkey” mothers instead. For one group of the infants, one mother dispensed milk but, made of coiled wire, was sharp to the touch, and one was essentially a cardboard cone wrapped in terry cloth and string. Harlow’s aim was to test out the assertion that there were five primary human drives–hunger, thirst, sex, pain and elimination–that would supplant anything that got in their way.

His experiments were deep and dramatic. The babies, taken from their real mothers, choo-chooed in fear, the lab filled with jungle sounds and with the smell of desperation as the tiny rhesus infants oozed loose scat, Harlow noting all this as evidence of high emotionality.

Was Harlow simply a cruel fiend? Probably not. He first performed his experiment in the 1950s, which was an especially cold time in child rearing, still influenced by behaviorist John Watson, who notably wrote in 1928 that parents should not kiss their children but should instead shake their hands before sending them to bed. However, Harlow had a hunch. He watched and waited, and as he did, something strange began to happen. The baby rhesuses crept along the floors of the cages. They came to “monkey” mother No. 1, the cardboard cone wrapped in terry-cloth towels and bits of soft string. They fingered the towels, taking them in their agile hands and then mouthing their rough yet soft surface. Mesmerized, they continued to stroke and sniff, while “monkey” mother No. 2, with a single but perfectly proportioned breast, sat on her side of the cage, ready to quell both hunger and thirst. Eventually the baby monkeys discovered her, and it didn’t take long for them to clamber up her side and sate themselves with milk, but that was that. They never hung around the milk mother. They never clung to her in fear, or batted her in playfulness. They never showed any kind of feeling for her whatsoever. All feeling, all cuddle, all touch and stroke were reserved for the terry-cloth-toweled mother who dispensed not a single drip, and yet, even so, the babies clearly preferred her, needed her.

Harlow was on the edge of a critical discovery that we, in an age of quarantines and COVID, may be forgetting. His experiment with the baby monkeys suggested that although thirst and hunger may be primary human drives, addressing them alone is likely not enough. What mammals need–what they crave–is the comfort of closeness, fingers interlaced, mouth to mouth, the mingling of breath, everything we can’t do as we angle to escape the exponential growth of this virus.

Research has amply demonstrated that when we touch one another a hormone called oxytocin gets released in the brain. Called the hormone of love, it is a warm wash that quells anxiety, fear, sadness, depression. It is present in huge amounts right after mothers give birth, allowing them to bond with their babies, but you don’t need to go through labor to get an oxytocin high; hand upon hand will do the trick just fine.

Even in times of health and wealth, depression looms at the periphery of many human lives, a black hole with some serious suction that can whoosh you off your sensible feet in five seconds flat. According to the CDC, nearly 1 in 10 Americans will experience a depressive illness within a given year. We lose loads of money to the syndrome in all sorts of ways–sufferers unable to get to work or, once at work, unable to fulfill their job responsibilities. The total economic burden is estimated to be a whopping $210.5 billion per year. And while we take sickness seriously, we do not, as a society, give mental illness its due, even when researchers uncover or discover biological markers or neural substrates to psychic suffering.

Now, forced to stand separate while the virus makes its rounds, we are all at risk for a descent into despair. In fact, since the beginning of the pandemic and its associated isolation mandates, Americans have been reporting more depression and anxiety than before the virus, with roughly 30% of adults reporting symptoms each week since April 23–nearly triple the amount during the same period last year, according to the CDC. Even as businesses begin to reopen, we are still urged to keep our distance, our masks on. Those who are considered high-risk must continue to remain isolated, and the handshake may be gone forever.

COVID has come, and it will, eventually, go, although what its exit will be like no one knows. Quarantine and social distancing may indeed be saving lives, and I, for one, would certainly not recommend anything in their place, but even as we do what we need to do to stay alive, someone should be watching out for a second, still secret pandemic on the heels of this one, a pandemic of depression born of loneliness and lack of touch. Unlike the baby rhesus monkeys, we cannot cling to towels and so seek succor. We have no surrogates that can take the place of hand upon hand, of tongue, of teeth, of torso.

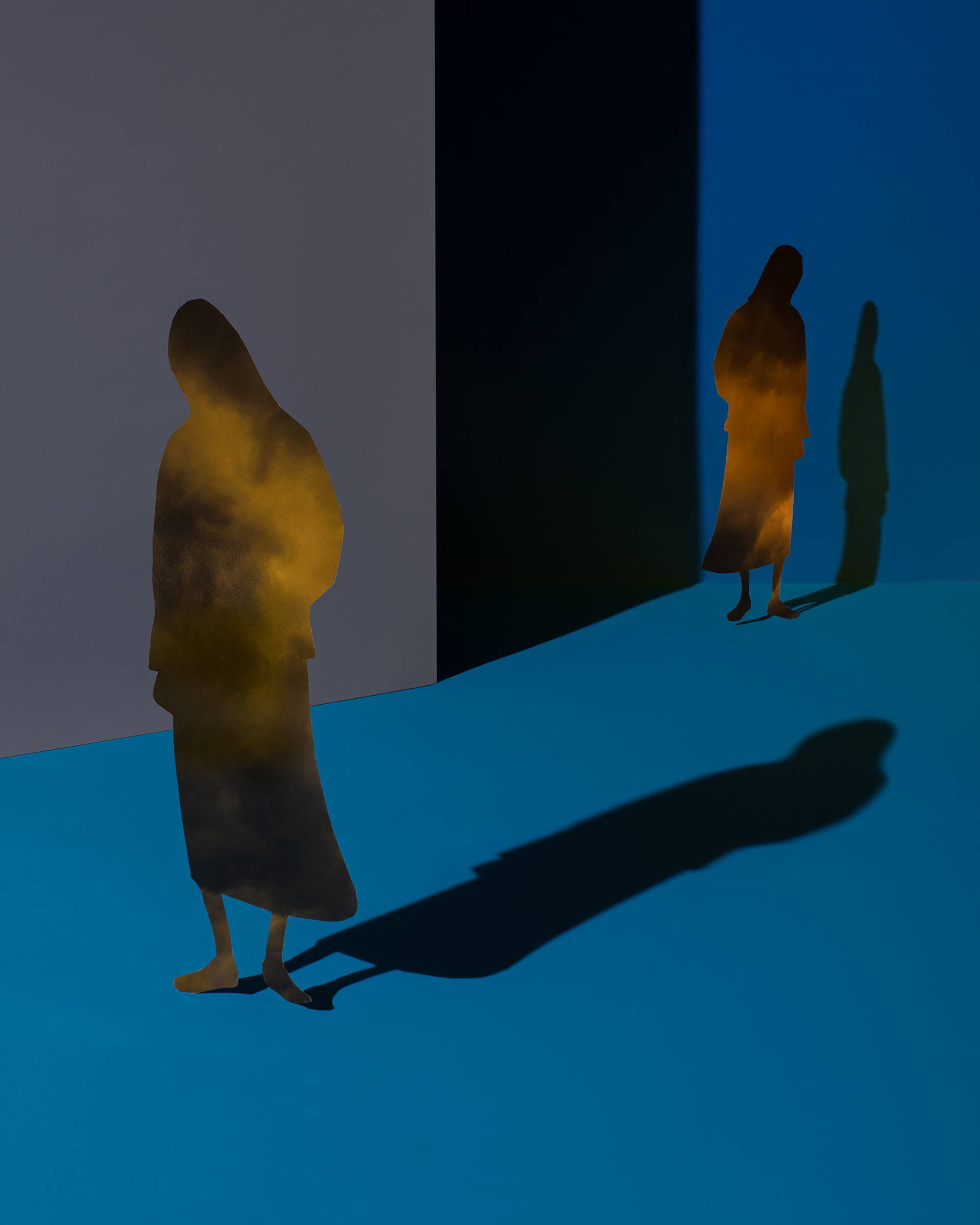

Deprived of intimacy and just plain friendliness, we are all at risk. Anyone who has been through a major depression will tell you it is big. It is scary. It robs you of will and words. It is the hopeless, lightless place, the ninth circle of hell. Will we be, are we now, husked humans? Will we adapt to these social conditions and become Spock-like, minus the ears? I doubt it. But I don’t doubt that depression is, if not right around the corner, for some at least already here, as we navigate the surreal world of contagion.

In the meantime, I lie in wait. I feel something solid in my stomach, something leadlike and heavy that makes movement difficult. My house sits in a valley surrounded by steep banks of loam. Craving color one day, I went to Home Depot and bought as many heather plants as I could cram into my car. The plants have spiky, stout branches on a mound of dry green, each branch studded with the smallest scarlet flowers that blow off in the barest breeze, leaving a litter of red in their wake. Shovel in hand I scooped out 20, 30 holes in that hill behind my house and dropped the heathers into their new homes, hoping they would root and return, somehow surviving the winter wind and ice to rebloom next spring in a time when COVID is behind us. I bent down and broke off a branch and held it up to the late light, the sun gilding it gold, the rip ragged, the innards green and living. Thinking of Harlow’s monkeys, I put the branch into my mouth and sucked hard, tasting a tang of something sweet and salty both, and for reasons I did not understand I suddenly had tremendous energy, a surge of good-will, hitched high on optimism, the sky above me purple and vivid, the clouds lit from within, the first stars faint, the sun seeping as she set. Next year, next year, next year. There would be, or might be, a time when the virus is behind us, when we are open again, when we can waft here and there and everywhere, my heathers healthy, glowing in the hill, night falling fast but the plants still beaming, as if they had sucked on some sun and were now stuffed with her light.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com