The traditional art gallery—the sterile, windowless viewing room aptly labeled the “white cube” by artist and critic Brian O’Doherty in 1976—has dominated the art world for decades as the primary way to display works. The white cube, which has been compared to an operating room as well as a burial vault, has been championed as a way to maintain neutrality while viewing artworks. “The outside world must not come in, so windows are usually sealed off. Walls are painted white. The ceiling becomes the source of light. The wooden floor is polished so that you click along clinically, or carpeted so that you pad soundlessly, resting the feet while the eyes have at the wall. The art is free, as the saying used to go, ‘to take on its own life,'” O’Doherty wrote in Artforum.

But its eerie, clinical neutrality comes at a price. The cube creates something artificial about the way the viewer interacts with art, removing both from the outside world, and from anyone who doesn’t seek out or stumble upon that room. The cube has been perceived as a symbol of elitism: if you didn’t dress the right way or frequent certain neighborhoods, the cube and its contents were not for you. And if you didn’t know the right people, the chances of your work being displayed there were even slimmer.

Now the pandemic has made the gallery even more inaccessible, at least temporarily, inspiring curators and creators to reimagine how art might be shared. But while today’s circumstances are new, artists’ efforts to think beyond such restrictions are not. In the 1960s, members of the Fluxus movement created works that blurred the distinction between art and life and denounced the gallery’s formalities. Everyday acts could be works of art, and many of the works could not be restaged or reproduced in full. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece, in which the artist sat on a stage with a pair of scissors and invited audience members to take turns cutting off her clothing, blurred the relationship between the viewer and the art, and threw into question any sort of neutrality.

The land-art movement of the ’60s and ’70s saw artists sculpt the earth to create large-scale works, like Robert Smithson’s 1,500-ft.-long Spiral Jetty made of salt crystals, water, and basalt rock on Utah’s Great Salt Lake, that inherently held their creators’ anti-commercial politics: other than in photographs, there was no way for the massive pieces to exist within four walls. The “earthworks” made during this period were the antithesis of what the white cube represented; rather than existing in a void that nullified the outside world, these works were the outside world.

As galleries have shuttered during social distancing and stay-at-home orders, this spirit of creativity, if not outright anti-establishment thinking, has informed new relationships between art and viewers. From video games to snail mail, the examples below are just a few of the ways artists and museums have seized upon this difficult moment to prove, yet again, that possibilities for interacting with art are as wide open as a room is closed.

A Miniature Gallery

On March 27, artist Eben Haines launched Shelter in Place Gallery, a miniature display room that allows artists to create small-scale works that appear larger when photographed and shared on Instagram. After reviewing artists’ submissions of sample images and proposals over email, Haines and his partner Delaney Dameron ask the selected artists to drop off or mail them their work. Then they install and photograph each tiny solo art show, which lasts for less than a week.

“The fact that the space is miniature, and that the viewer understands that it is a fabrication, means that they end up looking closely at details: the masonry and the conduit and poorly placed outlets, the water stains where the skylight has leaked,” explains Haines.

For artists who don’t have access to their studios now, creating small works is far more feasible than what their usual work might entail. They’re “able to make more ambitious work than they could ever afford to at scale, let alone have shown in a commercial gallery,” says Haines, referencing the prohibitively high cost of real estate for urban galleries that might otherwise show more large-scale works.

Exhibited artists include B. Chehayeb (whose work is shown above), who makes paintings of abstracted memories of growing up Mexican American, as well as Mary Pedicini, who created a mixed-media room installation that hung from the beams.“ Hopefully,” Haines says, “we allow people to make the work they’ve always wanted to make.”

Video-Game Curation

In 2020, you can have your very own Claude Monet or Vincent van Gogh—or at least a pixelated version hanging above the stove in your virtual kitchen. With the Los Angeles–based Getty Museum’s Animal Crossing Art Generator tool, players of the highly popular Nintendo game—in which users design a whimsical island world while befriending the animals that inhabit it—can search through the museum’s open-access collection and import images into their game. Then, players can display each work however they choose: on a wall; on a piece of clothing; or even in their own galleries, which friends who are also playing the game can visit virtually.

Bringing works of art into a video game and inserting them into a fictional world changes their contexts entirely, making them playful, moldable items. Players, in a sense, become curators. “It doesn’t just give users access to our collections, but it allows them to shape the museum experience for themselves,” says Selina Chang-Yi Zawacki, a software engineer at the Getty who developed the project. “In general, the typical museum experience is very rigid. It’s set up for you; there’s a flow you have to follow—but with this tool, you can make it whatever you want.”

Some users have chosen to print out the digitized versions of their chosen works, bringing the digital back into the physical world. The Art History Undergraduate Association at the University of California, Irvine, even used the tool to add works to a virtual art show honoring the opening of a canceled campus exhibition.

Mail Art

The decades-old populist art practice commonly known as mail art or postal art has seen a revival in recent months. The rules are simple: all one has to do is make a small work of art of any kind (drawing, collage, poem, etc.) that can fit into an envelope and send it through the mail to another correspondent.

Dada artist Marcel Duchamp, Fluxus artist On Kawara and many others practiced the form in the late 20th century. The movement gained prominence in the 1950s, when Ray Johnson, who wanted to rebuke the gallery system, encouraged his network of acquaintances as well as strangers to share work through the mail. Johnson would send templates that had copies of his own drawings with prompts, like “Please add hair to Cher,” to correspondents, who would add their own mark to the mailings before returning them to him or forwarding them to someone else. The project eventually became known as the New York Correspondence School.

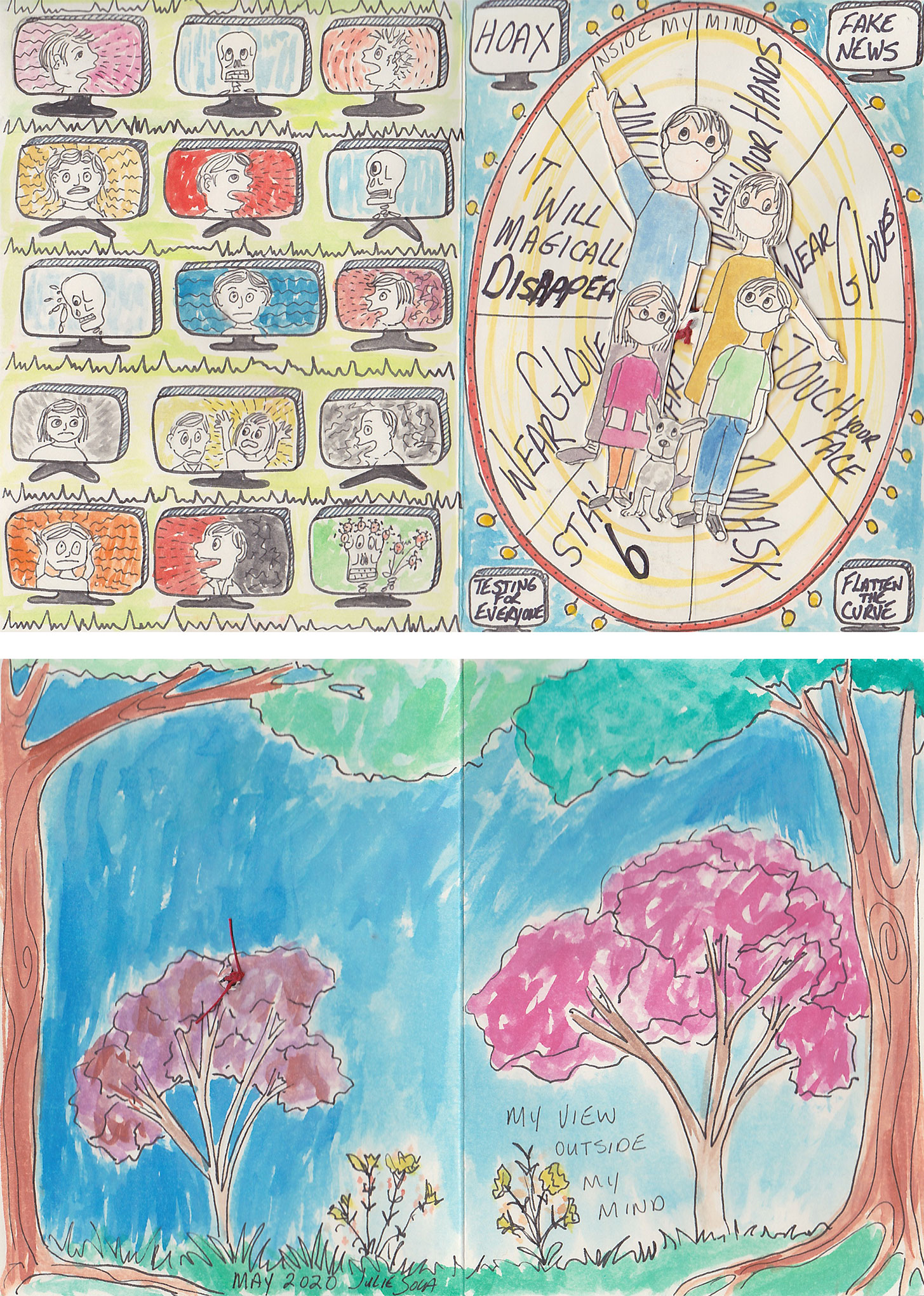

Since stay-at-home orders took effect, several mail-art projects have emerged. For one such project, Nashville-based art collector and curator Jason Brown has been holding an open call called “my view from home.” The initiative invites people everywhere to send in their works, which Brown collects and posts to the project’s website and Instagram account. After the submission period is over, Brown plans to donate the mailings to the Special Collections at Vanderbilt University Library in Nashville. According to Brown, he’s received more than 350 works from 27 countries, including India, Cuba and Germany. “It expands the notion of what an artist is. Mail artists come from all walks of life; most are not professional artists,” says Brown. “All you need is your imagination and a stamp.”

Jason Pickleman, a Chicago-based graphic designer and gallerist, held a mail-art exhibition over Instagram Live and plans on divvying up the 600 artworks he’s received in the mail into smaller groups that can be mailed out as “a lending library to anyone interested in experiencing the collection.” The project, titled “MAILL” (Mail Art Inventory Lending Library), aims to create “a museum from your mailbox,” as Pickleman puts it, and allows for art viewing to become a more tactile and intimate experience. Plus, according to Pickleman, it’s nice to open your mail and discover artwork rather than utility bills or mail-order catalogs.

“Drive-By” Exhibits

Organized by Los Angeles–based conceptual artist and theorist Warren Neidich, “Drive-by-Art” is a unique blend of the physical and digital that creates a socially distant art experience. Aimed at bringing art back to its starting place, the artist’s studio—where Neidich believes the work is in its purest and most powerful state—his shows allow spectators to use an online map to drive past works displayed on artists’ lawns, porches and mailboxes from the safety of their cars. He came up with the idea after being sequestered in a cabin at the start of the pandemic; “Drive-by-Art” was his “reaction to feelings of isolation and disconnection.”

Neidich has already completed shows in L.A. and New York’s Long Island, and plans to expand to more cities and countries. Exhibits have included Jeremy Dennis’ “Destinations,” wood silhouettes covered in photocopied images of the Eiffel Tower and Elvis’ meeting with President Nixon. Neidich worked with local artists and curators Renee Petropoulos, Michael Slenske and Anuradha Vikram to ensure a diverse range of both established and emerging voices for the expanded Los Angeles show. “I was using the car, which has many functions in the history of America, like the building of suburbia, and was trying to give it another meaning as a place of protection, a kind of solitary bubble through which you could experience art,” he explains.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Anna Purna Kambhampaty at Anna.kambhampaty@time.com