As Black Lives Matter protests have forced a political and cultural reckoning in the wake of the death of George Floyd, advocates and officials alike early on faced the question of how to talk about the incidents of looting that accompanied some early demonstrations.

The split on the issue was wide: President Donald Trump echoed an infamous 1967 moment when he tweeted that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts”; Trevor Noah has said that it’s more important to remember that “police in America are looting black bodies.” Some have pointed out that the examples of looting have been separate from the largely peaceful demonstrations, while others have argued that it is nevertheless counterproductive to protesters’ goals.

But, historians say, it’s not surprising that observers today disagree on how to talk about the subject: perceptions of looting evolve over time—and in the United States, race has always been part of that evolution.

In its early days in the English language, the word—which, in the 1700s, crossed over from a Hindi term, “lut,” used in reference to prizes plundered from wartime enemies—didn’t always come with the connotations of lawlessness it has today. It was a sort of military slang at first, used by soldiers during the British rule of India, and spread during mid-19th century conflicts. Eventually it moved beyond the realm of war, applied, for example, to artistic and historical artifacts plundered by Western nations from other countries. “Went to see Marshal Soult’s pictures which he looted in Spain. There are many Murillos, all beautiful,” the Earl of Malmesbury wrote, nonchalantly, in his autobiography, Memoirs of an Ex-Minister, in 1847.

As the word became more and more widely used, it brought with it negative connotations. Throughout U.S. history as well as now, a wide array of activities have been grouped under the term looting, from politically-motivated property destruction to opportunistic theft.

“Looting is as American as apple pie,” says William F. Hall, a former field office director for the Department of Justice’s Community Relations Service Division who now teaches political science at Webster University, Washington University in St. Louis and Maryville University.

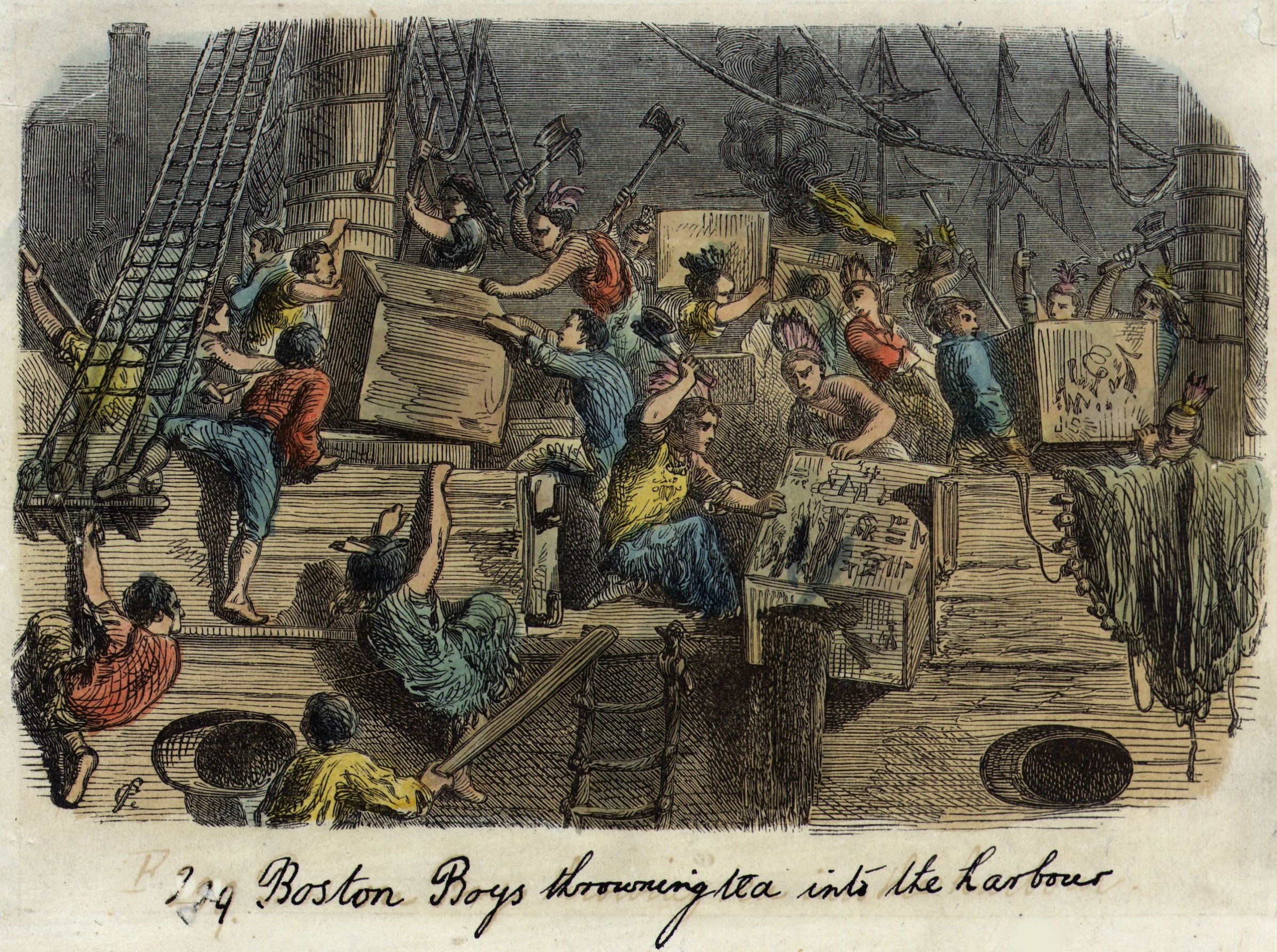

Perhaps the most famous early American example took place in 1773 when, in opposition to the Tea Act, which was enacted by the British government without the input or approval of colonists and hurt certain colonial business interests, American protesters climbed aboard three British ships and dumped 45 tons of tea, worth an estimated $1 million, into Boston Harbor (enough for more than 18 million teabags). This seems to fall clearly under the umbrella of what would be recognized today as “looting,” but it didn’t take long for the event to acquire its mythic sheen. Though at first it was just referred to as “the destruction of the tea,” by the 1820s, newspapers started to call it the “Boston Tea Party.”

“The founding fathers use looting as a supplement to protest. You can go back as far as the Boston Tea Party at the time the United States was a colony of England, and they saw fit to literally go and loot and destroy cargo on ships that were owned by England,” says Hall. “From the very, very beginning of our nation, looting has been a part of protests.”

The Boston Tea Party, though not widely portrayed as looting, is an illustrative example of some of the ways in which the term is applied, says Matthew Clair, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Stanford University: as the word looting had taken on a negative tone, it wouldn’t be applied to the actions of those in power. This is likewise the case for the way Americans have tended to discuss colonial treatment of Native American land and property, he adds. The history-shaping actions of white people are rarely remembered as looting, even when they have involved seizing goods by force, whereas the word is freely applied when those doing the seizing lack power. Because of the racial history of the United States, that dynamic has meant that the term often has racial implications too. “The term is racialized and is often used to condemn political acts that threaten white supremacy and racial capitalism,” explains Clair.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

These same dynamics persisted into the 20th century.

During the “long, hot summer” of 1967, for example, stories of looting were given prominent placement in mainstream discussions of the riots sparked by racial inequality in cities like Detroit and Newark, N.J. “To keep the arrested off the streets until the city stopped smoking, bonds were set at $25,000 for suspected looters, $200,000 for suspected snipers. Said the harassed judge to one defendant: ‘You’re nothing but a lousy, thieving looter. It’s too bad they didn’t shoot you,'” TIME reported in a cover story on the uprising in Detroit.

A more recent example of the racial dynamics of the perception of looting made headlines in 2005. Looting after large-scale disasters is not uncommon, for the obvious reason that people may have little choice but to seek out basic necessities however they can. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, one news image, shared by the Associated Press, was captioned as “A young man walks through chest deep flood water after looting a grocery store.” But a similar photo, shared by AFP/Getty Images, was captioned, “Two residents wade through chest-deep water after finding bread and soda from a local grocery store.” After both were published on Yahoo News, some readers demanded an apology after noticing that the biggest difference between the photos was the race of the subjects: the “looting” photograph was of a black man, and the “finding” photograph was of white people.

In today’s situation, analysis of the perceptions of looting has been complicated by questions about the relationship between the protesters and looters. Some people who have participated in looting have had little or nothing to do with the protests but are merely taking advantage of the crowds; for example, Tampa police said that 40 businesses were damaged in just one weekend of protesting, according to the Tampa Bay Times, but protesters said many of those people were not part of the movement themselves. “They have nothing to do with this. I am afraid the media wants to portray us as these crazy animals who are doing this,” Teddy Holloman, a protester, told the Times.

This type of looting, according to Kabria Baumgartner, an Assistant Professor of American Studies at the University of New Hampshire, is an “unfortunate byproduct” of protest that takes the attention away from the issue that gave rise to the demonstrations in the first place. For this reason, some protesters have attempted to stop acts of looting, and George Floyd’s brother Terrence Floyd chastised people “messing up my community” at a Minneapolis memorial on June 1.

At the same time, however, many experts today agree that a small portion of non-peaceful actors at the demonstrations may have been protestors looting for political reasons. “[These instances] could be understood as one of many tactics protesters believe are necessary to get the attention of the media, political leaders, and ordinary citizens who have looked the other way at state-sanctioned violence for far too long,” says Stanford’s Clair. That pattern could be seen in the Ferguson, Mo., protests of 2014 after the police killing of Michael Brown, writes Vicky Osterweil in her essay In Defense of Looting: “If protesters hadn’t looted and burnt down that QuikTrip on the second day of protests, would Ferguson be a point of worldwide attention? It’s impossible to know, but all the non-violent protests against police killings across the country that go unreported seem to indicate the answer is no.”

Since its first uses, the word “looting” has affected how any event or protest is perceived. Now, as many non-black Americans re-examine the role of race in their own beliefs and actions, looting has likewise come in for new consideration. In addition to the age-old factors and questions about who counts as a looter and what looting means, people are asking themselves whether it’s time to ask a new type of question.

For example, in response to one person’s sympathetic tweet about a looted Macy’s store, Jen Rubio, co-founder of the luggage brand Away, tweeted, “I urge you to redirect your empathy from Macy’s to the Black community. If you’re uneasy seeing a store being looted, imagine how it feels for Black Americans to see their community being looted daily through systemic racism. I say this as someone whose store was looted.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Anna Purna Kambhampaty at Anna.kambhampaty@time.com