As people across the globe take to the streets to demand justice in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, the case against the four now-former Minneapolis police officers involved in his death has already begun: Derek Chauvin, the white officer who pressed his knee to Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes, has been charged with second-degree murder, and the three other officers present with aiding and abetting. But lawyers representing the Floyd family, S. Lee Merritt and Benjamin Crump, aren’t looking only to the U.S. criminal-justice system. They have announced that they also plan to take the matter to the United Nations Human Rights Council.

Merritt and Crump also represent the families of two other African Americans who deaths have shocked the public in recent weeks—Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery—and have in the past worked on other high-profile homicide cases involving police brutality, such as Eric Garner and Michael Brown. And this isn’t the first time their clients have gone to the U.N.: in 2014, Michael Brown’s parents gave heart-wrenching testimony before the United Nations Committee Against Torture, in Geneva. That same year, the office of the Commissioner on Human Rights announced that the Garner and Brown cases “have added to our existing concerns over the longstanding prevalence of racial discrimination faced by African-Americans, particularly in relation to access to justice and discriminatory police practices.”

As Merritt and Crump approach the U.N., the involvement of the international community draws attention to a tension that has existed for more than half a century within the movement for African American rights. For much of the history of the Black Freedom Struggle in the United States, civic leaders and politicians used the term civil rights to characterize the objective of the movement to gain equal rights in this country; the period to which the current moment has been compared is known as the civil rights movement. But not everyone at that time thought that civil rights were the goal.

Malcolm X — who abandoned the philosophy of Black Nationalism in favor of the more inclusive Internationalism, a philosophy that aimed to encourage allyship with oppressed people globally — admonished black Americans in the mid-1960s to abandon the domestic agenda for civil rights in favor of an international agenda for human rights. In fact, this effort has been called the “unfinished work of Malcolm X,” which came to a tragic halt when he was assassinated on Feb. 21, 1965. The problem with civil rights, Malcolm argued, was that such a framing defined the matter as a domestic issue, focused on guaranteeing African Americans equal access to the rights of U.S. citizens. In his view, that limited the potential of the movement and left black people at the mercy of a government that had ignored its pleas for equality since the post-Civil War era.

Malcolm X was no stranger to police brutality. In Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, Manning Marable recalls a notorious incident involving Los Angeles police and the Nation of Islam (NOI) in 1962, which reads like a story ripped from today’s headlines. On April 27, 1962, while members of the Nation were delivering clothes from the dry cleaner to their mosque, two white police officers who were on a stake-out approached the men, believing the clothes were stolen. The details are murky on what followed. After some pushing and shoving and a call for back up, which bought at least 70 additional officers to the scene, the mosque was raided. What is clear is that 15 minutes later when the dust was settled, “seven Muslims were shot,” Marable explains. They included Ronald Stokes, a Korean War vet who was fatally shot from behind while trying to surrender. Less than a month later, Malcolm X delivered a blistering speech against L.A. city officials for their willingness to tolerate police brutality.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

By 1964, Malcolm X had split with his spiritual mentor Elijah Muhammad and NOI to launch what he called the Organization of Afro-American Unity, with a rallying cry for black people to set their differences aside for the common goal of Black Liberation. In his classic speech “The Ballot or the Bullet”—delivered twice, on April 3 and 12, 1964, less than a year before he was assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem—he channeled the sentiments of Revolutionary War patriot and slave owner Patrick Henry who in 1775, ironically, cried, “give me liberty or give me death.” Malcolm echoed these sentiments nearly 200 years later when he stated in the second iteration of the speech, “It’s the ballot or the bullet. It’s liberty or it’s death. It’s freedom for everybody or freedom for nobody.”

At the conclusion of this speech, Malcolm admonished black Americans to approach their freedom struggle from an international viewpoint, which would reframe the struggle as one not for civil rights but human rights, for which they would be entitled to seek the aid of the international community. “When you expand the civil-rights struggle to the level of human rights,” he stated on April 3, “you can then take the case of the black man in this country before the nations in the U.N.” He also explained how he saw the difference between civil rights and human rights:

You can take Uncle Sam before a world court. But the only level you can do it on is the level of human rights. Civil rights keeps you under his restrictions, under his jurisdiction. Civil rights keeps you in his pocket. Civil rights means you’re asking Uncle Sam to treat you right. Human rights are something you were born with. Human rights are your God-given rights. Human rights are the rights that are recognized by all nations of this earth. And any time anyone violates your human rights, you can take them to the world court.

His focus on human rights, however, didn’t mean he had given up on the possibility of winning civil equality within the United States. In fact, Malcolm believed that, while revolutions have historically been bloody, the U. S. was uniquely positioned for a revolution devoid of bloodshed, “[Today],” he stated, “this country can become involved in a revolution that won’t take bloodshed. All she’s got to do is give the black man in this country everything that’s due him, everything.”

Malcolm X, whose political philosophy of freedom was underscored by the mantra “by any means necessary,” called for a revolution that would overthrow the system of white supremacy rather than integrate blacks into it. Even so, like Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm believed that such a revolution could be achieved through nonviolent means. While he believed black people had a right to defend themselves if attacked, he counseled white America to listen to King rather than face the alternative.

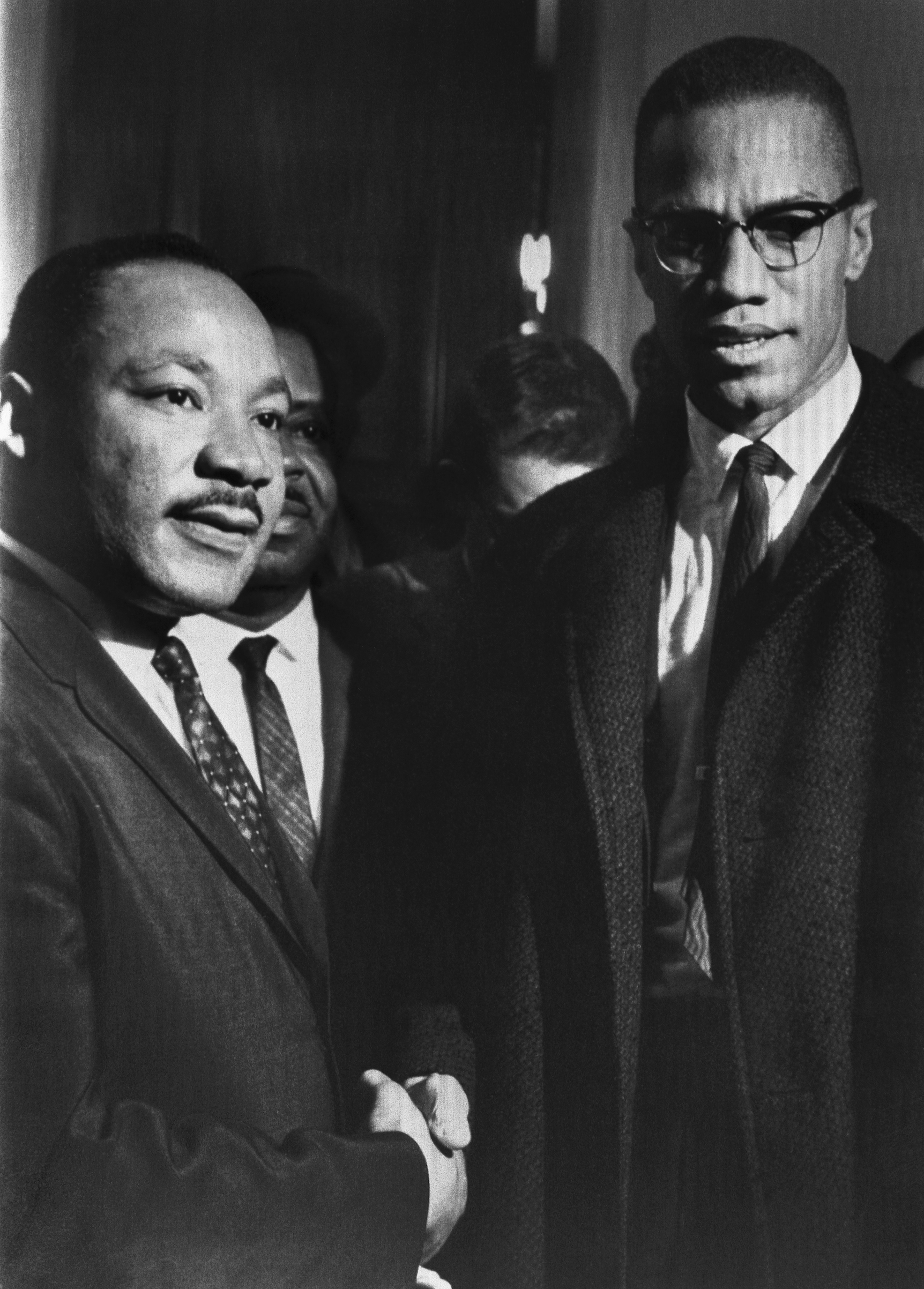

Just the month before this speech, Malcolm X and Dr, Martin Luther King Jr. had met for the first and only time. The two men were on Capitol Hill to attend a senate hearing on school segregation and employment discrimination. Malcolm, who had attempted on several occasions to reach out to King and had conversed extensively with King’s wife Coretta, approached the Southern minister with his hand outstretched. While cameras flashed as the two men greeted each other, Malcolm expressed his desire to be more involved with King’s movement. “I am throwing myself into the heart of the civil rights struggle,” he told King. He clarified his intent further in his speech the following month: “We have injected ourselves into the civil rights struggle,” he stated, “and we intend to expand it from the level of civil rights to the level of human rights.”

Today, as black America is still pressed under the weight of white supremacy and violence, including extrajudicial killings, that struggle continues. With a new generation embracing Malcolm X’s idea that human rights is the path to black liberation, the work of expanding the struggle continues too.

Historians’ perspectives on how the past informs the present

Arica L. Coleman is a scholar of U.S. history and the author of That the Blood Stay Pure: African Americans, Native Americans and the Predicament of Race and Identity in Virginia and a former chair of the Committee on the Status of African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American (ALANA) Historians and ALANA Histories at the Organization of American Historians.

Correction, June 18

The original version of this story misstated the current name of a United Nations human rights body. It is now called the U.N. Human Rights Council, not the U.N. Human Rights Commission.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com