Doug Barrett, 37, is a photographer, Army Veteran and former police officer from Atlanta who moved to Kansas in 2011.

I was a former police officer in Gwinett County, Ga., working in SWAT and narcotics. So, part of why I feel comfortable shooting photographs and getting into the thick of things is because I understand the law enforcement perspective. I understand being a black American with a camera in my hand.

I made a Facebook post last Thursday about my experiences to share with people in Manhattan, Kans., because so many people have been reaching out to me that I know in the community. They want to understand what is it that African Americans go through. What is it that they’re missing? How can we help come together and unite?

In the post I wrote:

So here it goes …

I’m not sure what to say as to not to offend anyone. I debated writing this. I laid in the bed Tuesday of this week all day and anyone who knows me knows this is not me. I was fearful as a business owner of a photographer who is seeking future opportunities I may limit my work. I’m sure I’ll lose some friends but enough is enough. You may not be able to comprehend the words that I write but I’ll share my heart with you. As a black man, I walk around with a camera making photographs but I’m not a threat. I have big hair and tattoos, but I’m not a threat. I wear a hoodie sometimes, but I’m not a threat I’m just cold. I may lean when I drive, but I’m not a thug, my back hurts most days because I had spinal surgery being a veteran.

Are you lost? Are you comprehending this? I recently walked in AutoZone less than a mile from where I live to make a purchase of jumper cables and was accused of stealing. The manager in a forceful tone told me to put what I stole on the counter or she would call the police. I made the decision in that moment to stand my ground. Oh, let me explain! Not stand my ground with a gun of right or wrong rather I knew if I left without pleading my case, that this moment could have been my last moment on this earth based on a black man’s history with police. Police were called on me, my rights read, searched, and finally released but I assure you I’m not a threat. This is everyday life. I came home cried inside only to know that what my father informed me of being black in America is what we expect. I’m almost 38 and this will not stop in until those in leadership positions accept the fact that this is real.”

Most of the people near to me can tell you I openly love and genuinely care but I assure you I’m not a threat. We are your statistics; we are you highest generating revenue race within jails but give us our day in the courts. At least we can breathe in a cell.

My camera dangles from my neck and my inhaler may be in my pocket but I assure you it’s not a gun. I’m a former police officer so I speak from experience, I’m a US military veteran, I have a master’s degree, I’m a Master Mason, Thirty Second Degree Scottish Rite, Knights Templar, I’m a member of Kappa Alpha Psi Inc, I volunteer at my church protecting the flock, and serve as an active member in my community yet because of the color of my skin and those who look like me will always be a threat.

Felony Forgery, Felony Theft, Felony Driving, Felony sitting on the couch, Felony pain who cares if you can’t breathe. It hurts we want to live.

I brought my children into this world as a responsible man and I love my children with my heart mind and soul, and I would do anything for them. My children love me as do I love them. I’ve worked hard to be where I am, I pray I don’t die in the streets making photographs.

I don’t have the answers, nor can I make the leaders in communities listen. They will only follow their own agendas because what we go through is incomprehensible to most. You may change your Facebook profile showing how you support and sending your many thoughts out to the world, but you will resume your everyday lives.

I can’t change the color of my skin but as your friend know when you walk out your door what you think about and what I think about is very different. I ask myself every day, do I look like a threat. Does my camera look like a gun, is my iPhone charged in case I need it while being pulled over to say my last words to my children? Or will I make it home.

I’ve been pulled over with my white friends in the car and I’ve narrated what will happen not because of my previous experience rather because its normal. But I assure you I’m not a threat.

I’m sharing this from the bottom of my heart, and I hope this doesn’t offend you, but this is my normal. Ill continue to make photographs, love, lead by example and walk upright until my day comes. My ask is that you help us. Our ancestors were brought over on ships and now were dying in the streets under the force of a knee.

The looting will end, and the store will recover. We can’t if we’re dead.

A concerned man, father, and photographer.

I’ve shared my personal experiences of what that looks like so that people aren’t just thinking that all cops are bad.

I was a police officer till 2011 and switched careers and joined the Army. When I came out west, and was stationed at 1st Infantry Division, in Ft. Riley, Kans.

I suffered some injuries while active-duty and took a medical retirement. Went through three surgeries to fix my back and lower extemeties. Being older, I said, you know what? I’ll take my chances being a civilian again.

After my service, I started my own company because I’d been taking images since my mom and dad gave me my first camera. I tried to find my space in the photo community, and I was determined to work on a veteran project. The documentary work, being a veteran, sharing the stories of homeless veterans in black-and-white portraits is where I find my heart.

I’m not 100%. I’m a disabled veteran. I don’t make any excuses, and I try to do the best I can each day, which is how that homeless veteran project started. I think I’ve gone to 17 states and taken black-and-white portraits of 75 homeless veterans in total. You can see them on my Instagram.

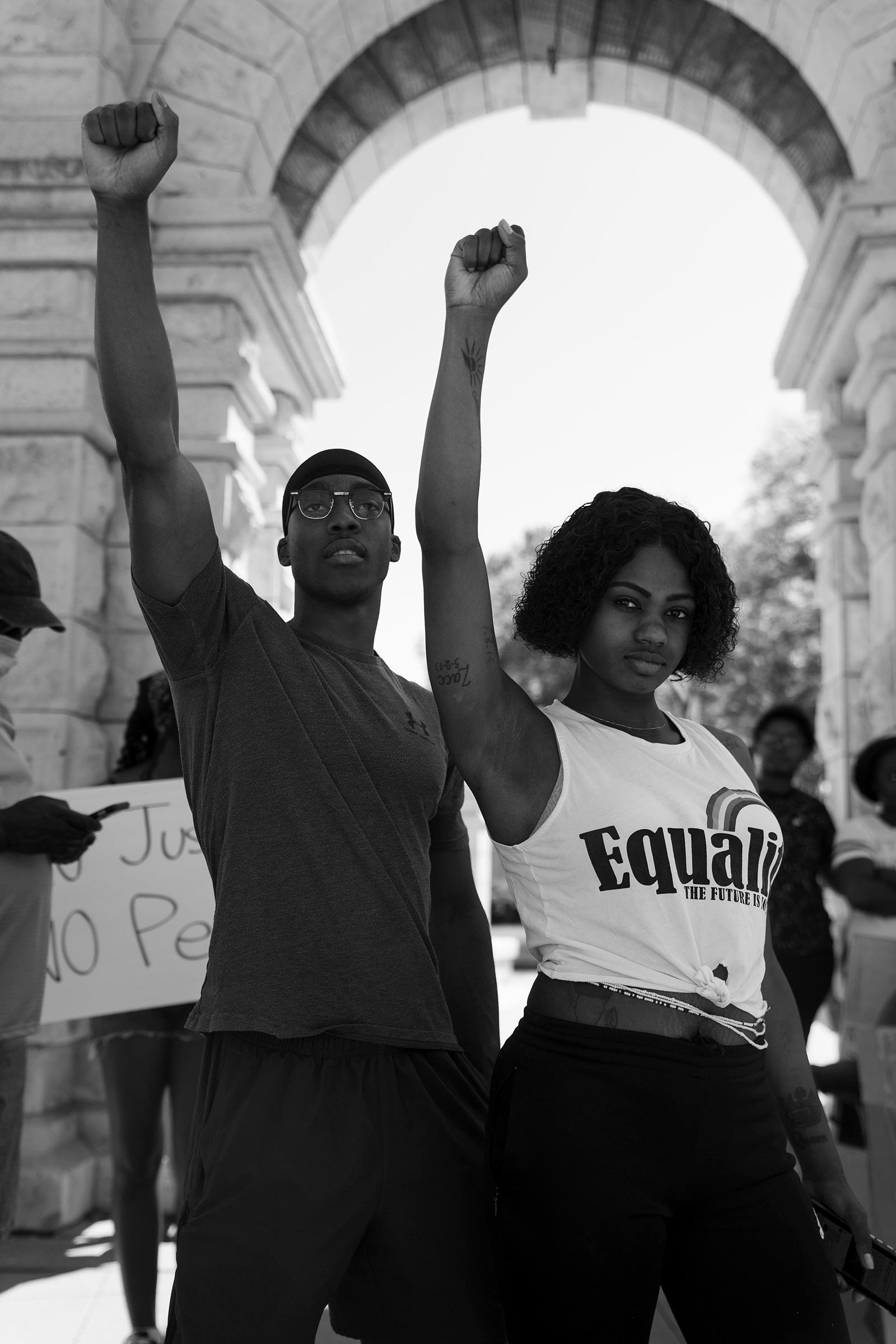

I went to photograph a protest last Friday. The two most impactful things that hit me the hardest were an image of an older African American female. She said, “I’m in my 60s, and I’m still having to protest.” I captured an image of her holding the another man’s hand.

Then I saw that I had photos of so many kids. And I remembered one of the ladies telling me she has an 8-year-old son, and she says, “My son, this is his second protest.” Because his first one was when Trayvon Martin was killed in 2012. I was like, wow, how heavy is that?

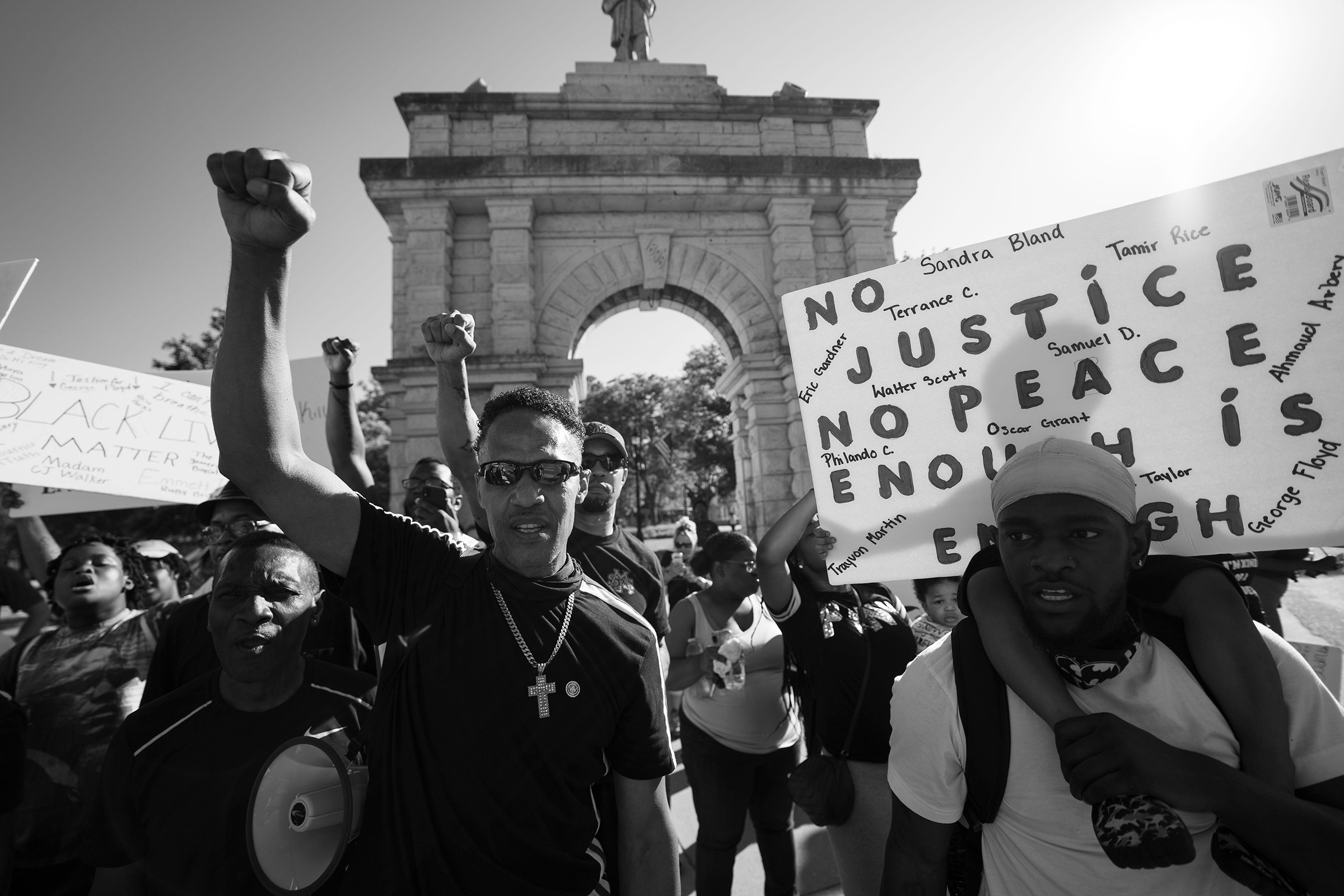

At the protest we counted about 105 people. The protest was staged by local leaders within the black community. As cars passed, people honked. People cheered, waved. They protested right there on the corner. Peacefully. No law enforcement.

They did march to the Geary County Sheriff’s Office. Two of the police officers were out there. People chanted and, voiced their concerns.

The officers smiled. They didn’t do anything reactionary to the protesters. And then the march continued back to its original point at Heritage Park.

I was with two other photographers and I decided rather than get in their space, I was going to go on the sidewalk. I saw a pop of light where I wanted to capture images. So, I started shooting and Jason Simmons with his siblings and his mom came right through that patch of light.

Two days later, I was culling through images, I was posting what I felt most of the people wanted to see. But then I was kind of reflecting. As a parent, I couldn’t even imagine taking my kid to a protest. Obviously, I’m shooting. Then again, people are taking their kids out there to see this, the experience.

I’m a contributor to @everydayblackamerica on Instagram. So just prior to going shooting this, they had asked me to start putting work out there to them. And they put the image on their page, and that’s pretty much the history on it.

Later on, the kid’s mother responded. Because somebody tagged her and said look at your babies in the picture. And her response was, “My heart just stopped. Oh, my God, this is powerful.”

When I see this photo of Jason, I think we just need to stop the hate. If we stop the hate, then we can make progress on how we fix these issues from the local level.

It’s about stopping the hate and educating, to get people to understand that this does happen. It is an ongoing issue and we just want to fix it. Nobody’s asking for anything. We just want to live.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com