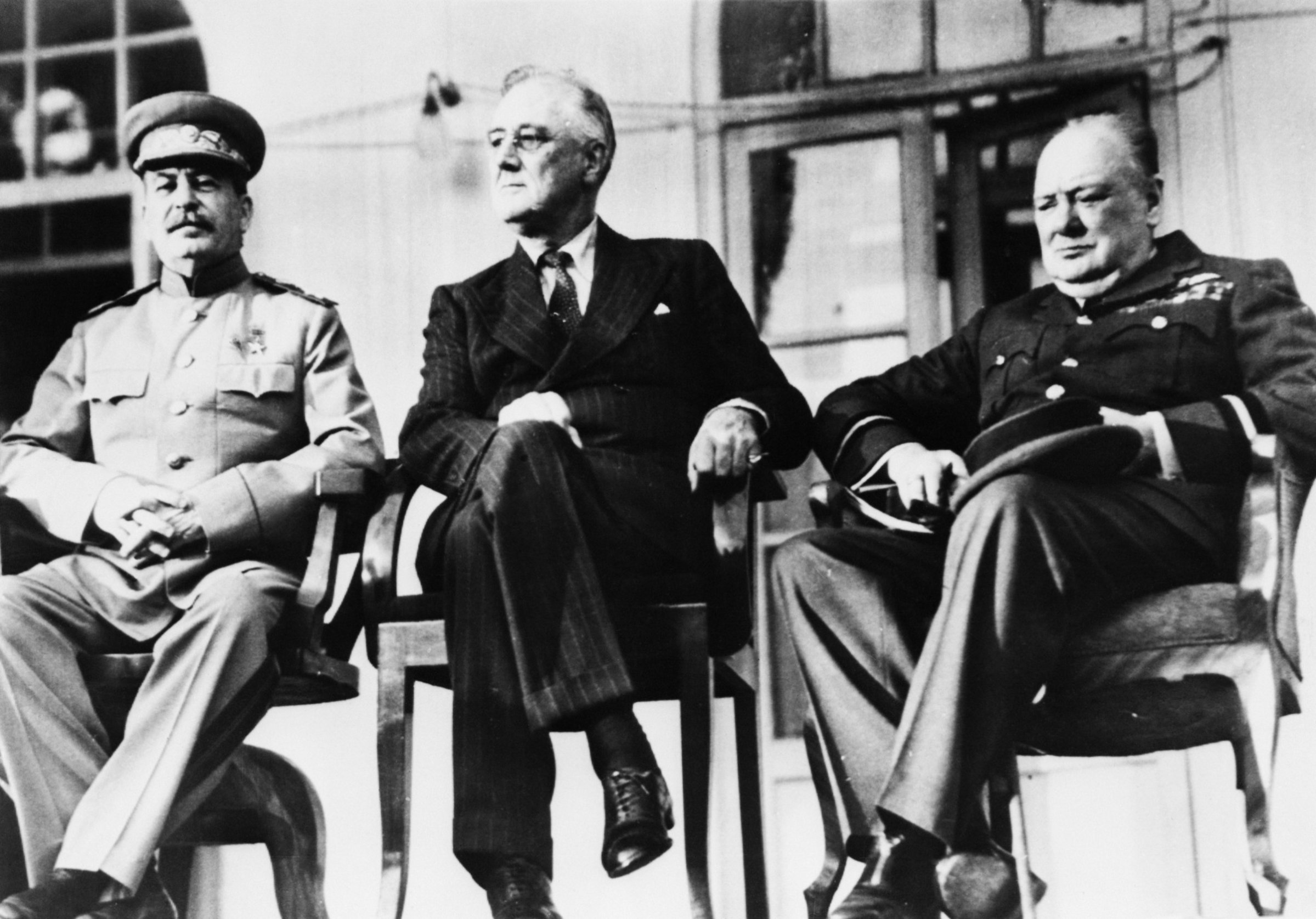

Reporters crammed into a tight semi-circle in the Oval Office, facing President Franklin D. Roosevelt as he sat in his wheelchair behind the walnut-veneered desk that had once been Herbert Hoover’s. It was Dec. 17, 1943, and the press had come to hear about the secret conference in Tehran where, just over two weeks earlier, FDR, Churchill and Stalin had met for the first time. As he discussed the meeting, about World War II strategy and plans for the post-war world, Roosevelt also disclosed something surprising — that, as the New York Times reported, the Russians had told him that there “was a plot endangering his life in Tehran, the knowledge of which caused him to move his residence from the American Legation to the Soviet Embassy.”

“In a place like Tehran there are hundreds of German spies, probably, all around the place,” FDR told the reporters. “I suppose it would make a pretty good haul if they could get all three of us going through the streets.”

After saying we wasn’t going to get into details, the president laughed his hearty, booming laugh, and the press, as can be heard on a recording of the session, joined in, too. There were no follow-up questions from the supportive war-time press corps. The president quickly moved on, talking about China.

And as the years, then the decades, passed, the actual events surrounding Operation Long Jump, as the Nazi assassination mission that targeted the Tehran Conference was known, remained a deeply buried official secret. The archives of the Wehrmacht, the Nazi military, omitted specific references to incidents, like the proposed killing of Allied leaders, that would be indictable offenses at post-war tribunals; “the very destruction of the fact, of the factuality of the fact,” was how one writer described the careful German practice. For details of how the plot unfolded during five days in Tehran in 1943, one had to consult memoirs (primarily by FDR and Churchill’s bodyguards) and journalistic accounts — some persuasive, others less so — that included postwar interviews with several of the participants in the events. But it was an exercise in battling through a swamp of half-truths, rumors and outright fabrications.

Then, on Nov. 18, 2003, with a drum roll rarely sounded in any spy headquarters, the Russian foreign intelligence service, the SVR, held a press conference to announce the publication of a new book. Tehran-43: Operation Long Jump, written by Yuri Kuznets, was a detailed account of the Nazi plot to assassinate the Big Three, and how the Soviets foiled the plot. It was based on the gold standard of espionage sources: previously classified Soviet intelligence reports, analytical documents from the Soviet secret police and decoded message traffic. Vladimir Kirpichenko, a former deputy chief of the KGB First Main Directorate (foreign intelligence) who had access to the Moscow Center archival material in the Long Jump files, was trotted out to add additional details about what had occurred in Tehran and to praise the book and its reproduced intelligence reports as “strictly documentary.” For further support, Gevork Vartanian, who as a teenager operative had played a key role in thwarting the Nazi plot, spoke and added his eyewitness imprimatur to the descriptions in the previously classified documents.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Historical battle lines have been drawn over Long Jump. At least one writer who has done groundbreaking archival research into the Nazi activities in Iran has dismissed the Russian version of events as mere historical revisionism, designed to make Russia look good and glorify the Stalinist era. On the other hand, an impressive collection of books and monographs published in the West gave accounts of Long Jump that, to varying degrees, matched the Russian version of events.

At the time, having written several books about long-forgotten espionage operations, I suspected the 2003 announcement represented a new opportunity. I could compare the Russian documents to materials in the British, American and German archives — and the archival documents, I soon realized, were pieces in a puzzle that I could assemble.

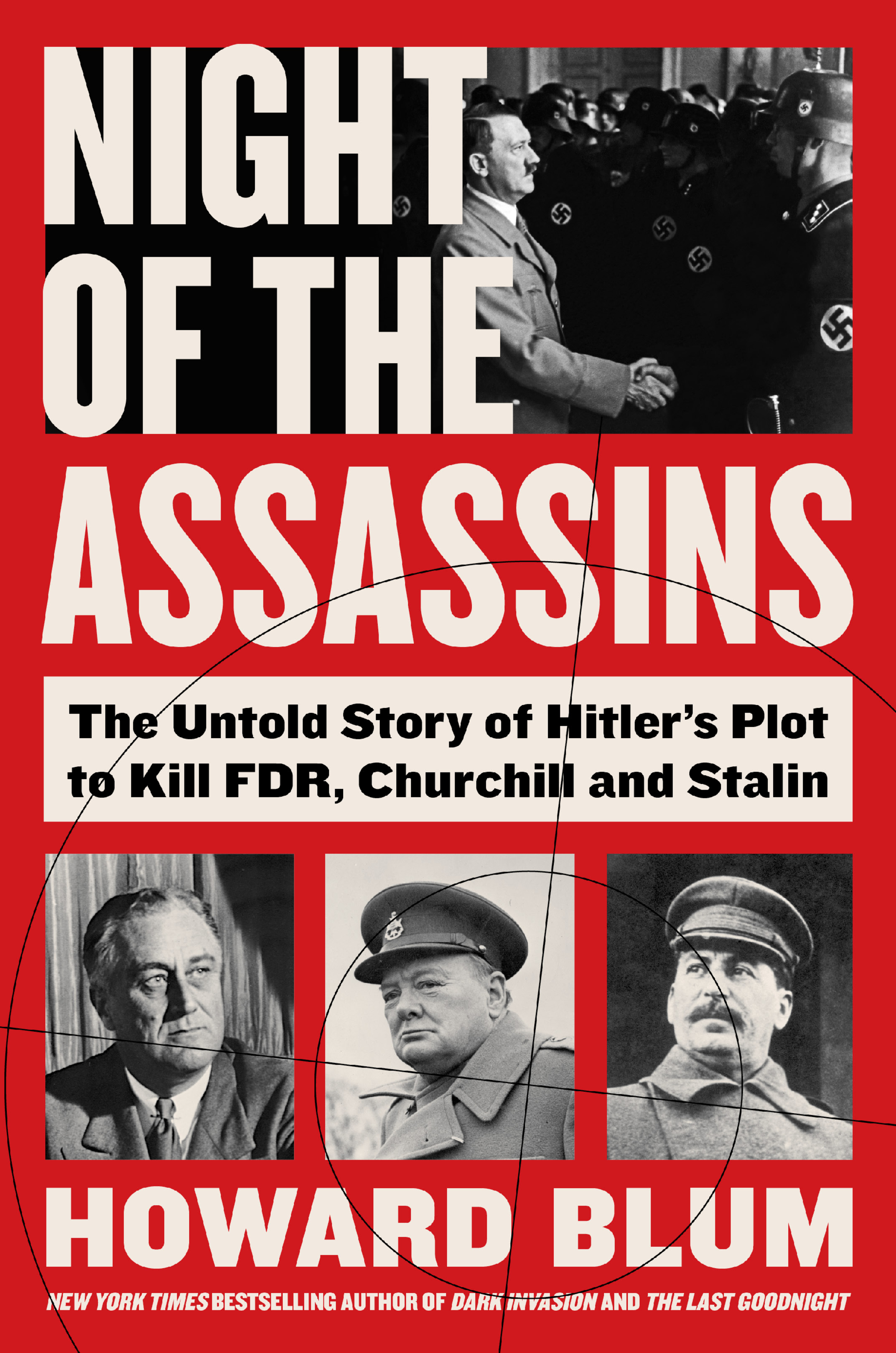

For example, there were detailed accounts in the German archives (and in memoirs) of commandos being parachuted into Iran. These coincide with both postwar interviews and the descriptions in Russian documents of the aerial insertions from a clandestine base in Crimea that were part of Long Jump. In addition, several of early accounts of the plot refer to a female asset who worked with the Reich intelligence operatives based in Tehran. These versions, however, gave her a pseudonym and spun an often-fanciful yarn. However, after I read recently declassified British and American intelligence assessments, it became clear to me that the asset had in fact existed, and she was a young woman named Lili Sanjari. Even better, the archival transcripts of her interrogations told a more compelling tale then I’d previously imagined and became essential element in what would become my book on Operation Long Jump, Night of the Assassins.

Still, the question of truth in any spy story proves daunting because intelligence assessments are fundamentally political dramas. Biases are proudly blatant. One man’s tale of Russian derring-do is another’s of Stalinist revisionism. The search for truth is, to use Sir Karl Popper’s phrase, the search for the best hypothesis.

It is useful, then, to consider what occurred as the SVR press conference in 2003 was about to conclude. A reporter asked, “Are there any secrets left concerning the Tehran Conference? And if there are still such secrets in the archives, when will they be disclosed?” Vladimir Kirpichenko, the former First Directorate chief, let the question float in the room for a long, pregnant moment. Then he answered: “I don’t think any intelligence service in the world opens up to the last document.”

Howard Blum is the author of Night of the Assassins: The Untold Story of Hitler’s Plot to Kill FDR, Churchill and Stalin, available now from HarperCollins.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com