If you closely follow the twists and turns in many of the most recent high-profile shootings of black men, you’ll notice a pattern. First, only the slightest and smallest level of alleged misconduct or “suspicious” behavior is used to justify the killer’s unreasonable fear.

And second, even after the smoke clears, all too many members of the public will understand, forgive and perhaps even share that deadly terror. Americans still impose upon black men the burden of their own unbalanced sense of risk. The injustice of the singular act of the shooting is magnified by a collective acceptance and defense of the shooter’s extraordinary alarm.

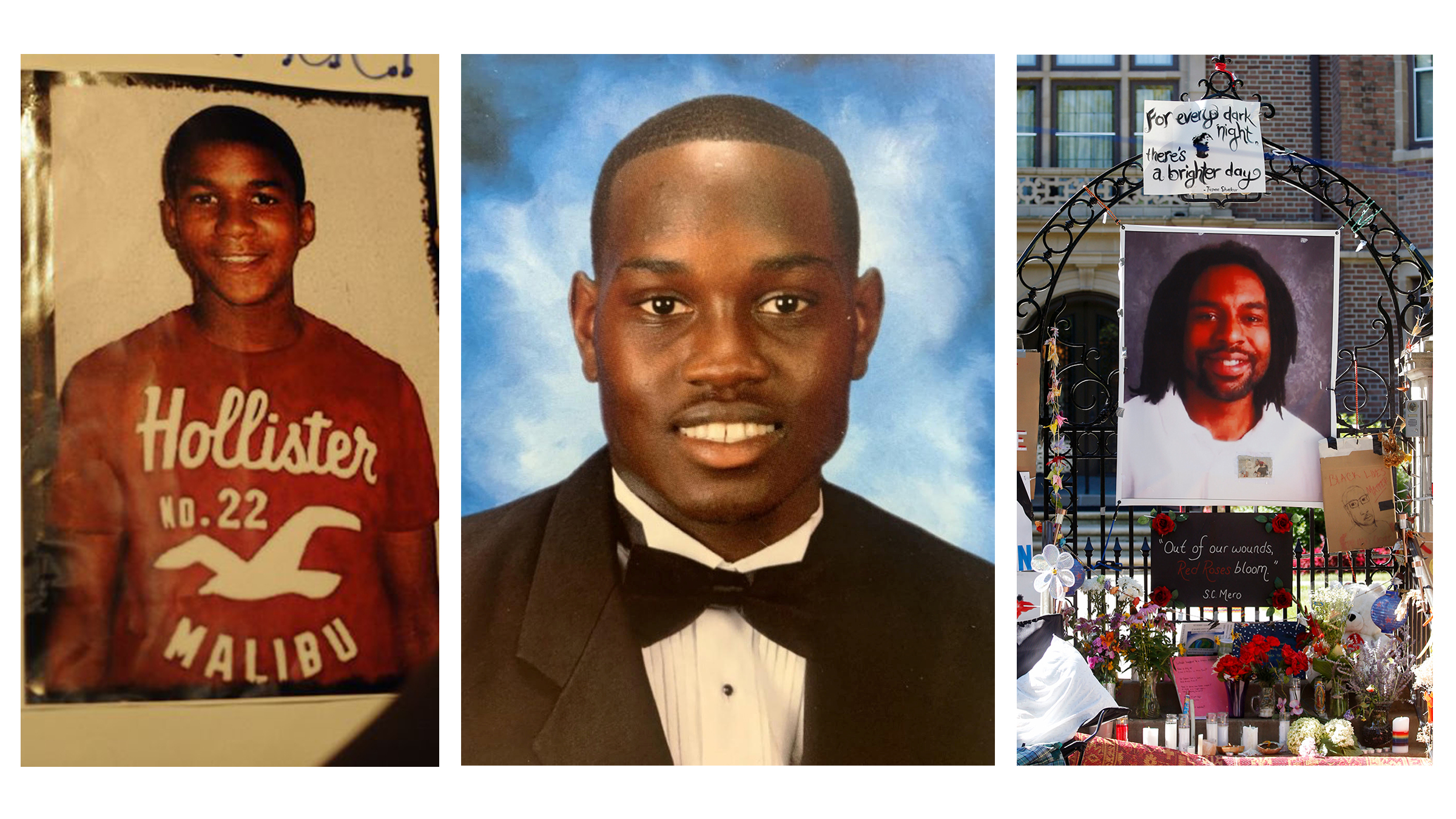

The pattern applies to the shooting of Ahmaud Arbery. The known facts of the case are simple and startling. On the afternoon of Feb. 23, two Georgia men, Travis and Gregory McMichael, saw Arbery running past their home. According to the police report in the case, these men thought he looked like a suspect in recent breakins, so they armed themselves with a shotgun and a handgun and–along with a third man–gave chase in two vehicles.

Eventually they cornered Arbery. One vehicle drove behind him, its driver filming the encounter. The McMichaels’ parked truck was in front of him, blocking his path forward. When he tried to run around the truck, Travis McMichael moved to intercept, holding his shotgun. Arbery and Travis scuffled, and the Georgia bureau of investigation said Travis shot Arbery, killing him.

The video was shocking. Why would these men arm them-selves and chase down a young man in shorts and a T-shirt who held no visible weapons? Gregory McMichael told police they thought he might be armed. Why? Because they’d seen him once put his hand down his pants.

That is the very definition of unreasonable fear.

As the case gained widespread public attention, evidence emerged that Arbery had likely been in a construction site shortly before he was shot. A 911 caller said he saw a man in an open, unfinished house. A video feed showed someone who looked like Arbery standing in the site. There was no immediate evidence that he committed a crime. He simply stood in an empty, open building–something countless curious Americans do as a matter of course.

Yet that very allegation, as innocuous as it is, was enough for some conservatives to come to the McMichaels’ defense. For example, conservative commentator Tomi Lahren compared the claim that Arbery was “just out jogging” to the false claim that Michael Brown had his hands up when he was fatally shot in Ferguson, Mo.

Another conservative commentator, Candace Owens, attacked the claim that Arbery was “just a jogger” and said he was “caught on camera breaking into an unfinished property.” But even if true, that action in no way justifies an armed two-car pursuit, and it certainly doesn’t permit private citizens to attempt to seize Arbery at gunpoint. That’s not the only trivial action or suspicion that contributed to a deadly attack. I’ll never forget the extraordinary statement of Jeronimo Yanez, the officer who shot and killed a young black man named Philando Castile during a traffic stop after Castile told Yanez that he was lawfully carrying a firearm. It’s hardly unusual for a motorist to lawfully carry a firearm, and video of the encounter shows that Castile was complying with Yanez’s instructions when he was shot. That same video shows Yanez rapidly escalating the encounter. What was one reason Yanez became so instantly afraid? Why was he so immediately convinced that a calmly speaking Castile was a deadly threat?

Because Yanez smelled marijuana. Yanez told investigators that if Castile “has the, the guts and the audacity to smoke marijuana in front of the 5-year-old girl and risk her lungs and risk her life by giving her secondhand smoke and the front-seat passenger doing the same thing then what, what care does he give about me?” And lest anyone believe that Yanez’s statement was too unreasonable to truly believe, re-call that a Minnesota jury acquitted him of second-degree manslaughter charges.

There are just too many tragic examples. Do you remember the killing of Walter Scott? He was shot in the back in 2015 by a South Carolina police officer named Michael Slager as Scott fled from a scuffle. He was unarmed. Why did the officer shoot an unarmed black man in the back? “I was scared,” Slager told the jury. He said that in his mind was “total fear.” A 33-year-old cop was terrified of a 50-year-old man running away.

One of the most traumatic fatal confrontations in recent U.S. history–the killing of Trayvon Martin–began when George Zimmerman called 911 to report that Martin “looks like he’s up to no good. Or he’s on drugs or something. It’s raining and he’s just walking around, looking about.”

That was the sight that led an armed man to follow a teenager. There were no weapons visible (Martin was un-armed). There was no evidence of any criminality.

When the case dominated public attention, a number of right-wing sites combed through Martin’s history, publicized evidence of past drug use and speculated whether he was a drug dealer. They were looking for reasons to justify Zimmerman’s pursuit. As Shermichael Singleton recalls in the Washington Post, Geraldo Rivera went so far as to identify Martin’s hoodie as a material factor in his death. “If he didn’t have that hoodie on,” Rivera argued, “that nutty neighborhood watch guy wouldn’t have responded in that violent and aggressive way.”

The legal outcomes of these cases vary. A hung jury protected Slager before he pleaded guilty to a federal civil rights offense. Juries acquitted Yanez and Zimmerman. And the Arbery murder case is pending, the McMichaels having been arrested in May. Juries acquitted Yanez and Zimmerman. But each case was dominated by obvious, outsize perceptions of threat and danger.

And, rather than rightly being seen as a badge of shame, the shooters’ paranoia actually unites their defenders in righteous indignation.

How can this be? In part because a part of the U.S. population shares the same perceptions of threat as the shooters themselves. They look at the McMichaels and sympathize with their armed pursuit. They think it was just fine for Zimmerman to follow Martin. And if police officers felt afraid, who are they to second-guess the boys in blue?

Put another way, there are Americans who would never pick up a weapon and try to track down a black man running on the street–or follow a young black man on a rainy night–but they understand and sympathize with those who do.

There is no easy cure for an unbalanced sense of risk. One can flood the zone with statistics about reduced crime. Juries can hold cowardly killers accountable. Outrageous video clips can raise awareness and slowly open eyes. But–at the end of the day–the battle is over the state of the human heart.

Make no mistake. Hearts can change. There was a time when my own first instinct was to disbelieve that injustice and prejudice could still be so profound. Surely, I would think, there was a “rest of the story.” And yes, sometimes there was. Sometimes, initial reports of police or citizen misconduct were wrong.

But all too often those reports of mis-conduct were right. All too often they are right. In fact, those reports are right so often–with so many Americans defending the indefensible–that I realized that all too many of these cases carried with them a dreadful double injustice. There was the awful death itself. Then there was the public declaration that there was something right about the alarm and even terror that triggered deadly violence.

It’s that second injustice that helps perpetuate the cycle of violence. It teaches a new American generation that when black men do even small things, then there is a reason to grab a gun–and even to fire that gun. The battle for hearts and minds must continue. It must be relentless and urgent–until at long last there is no real market for rationalization. After all, there is no reason a walk through a neighborhood at night or through an open construction site, or a whiff of marijuana in a car, should create in any American that terrible and fatal sense of unreasonable fear.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com