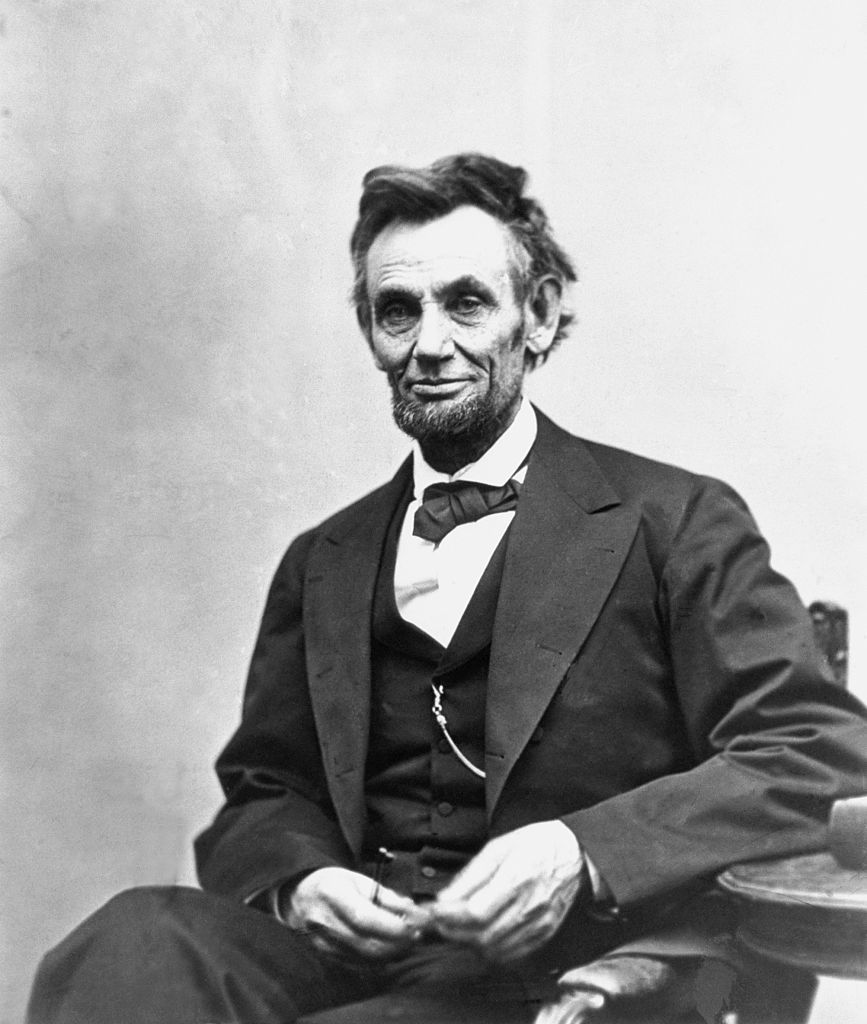

Abraham Lincoln needed votes. In January of 1864, as the Civil War raged on, the president was gearing up for a re-election campaign, believing his loss was imminent. But in order to unify the shattered pieces of the nation and abolish slavery, he needed four more years. With more time, he could end slavery with a law, but that law needed votes, which, by his own count, he knew he didn’t have.

In his hunt for votes for his re-election and for this new law, he turned to a map of the United States, focusing his dark eyes on a newly formed territory called Nevada.

By turning Nevada into a state, its citizens could vote for Lincoln’s second term. Votes from Nevada’s two Senators and one Representative would provide the margin Lincoln needed — not just to win a second term, but to ratify the 13th amendment and clinch the abolition of slavery. All he had to do was put some finishing touches on this untamed territory to transform it into an acceptable candidate for statehood — and quickly. Elections were around the corner and Lincoln was at the mercy of the slow legal machinery of Congress to make his plan work.

Many of his cabinet members advised him against admitting the rough-and-tumble Nevada. For them, statehood was like a marriage: Once a state was created, there was no getting rid of it amicably. One cabinet member told Lincoln that Nevada was “superfluous and petty.” The mining of gold and silver from the Comstock Lode gave birth to Nevada as a territory and with these riches came the tradition of vice, particularly drinking, gambling and womanizing. As future states went, Nevada looked pretty shabby.

But, Lincoln thought about the weekly military reports that tallied the thousands of Civil War casualties. “It is easier to admit Nevada,” he told Charles Dana, his Assistant Secretary of War, “than to raise another million soldiers.” The math was simple in Lincoln’s mind, for a new state could cast three electoral votes, votes he needed for reelection. “It is a question of three votes,” said Lincoln “or new armies.”

Nevada, he reasoned, was his best chance to vote for him and his Republican party. While Nevada wasn’t as populated, it was pro-Union, since many of the residents came from the North, and it was also pro-Republican in the truest sense of the word: It believed that power resided in the federal government, and that the federal government should intervene with economic policies. Nevada had also been a team player. It guarded the Overland Mail route, which allowed the East to communicate with the West via stagecoach, and also Nevada contributed hundreds of millions of dollars from its mines, offsetting the cost of the Civil War.

To help the birth of the state, an Enabling Act was approved by Congress to start the process of putting this largely uninhabited territory on equal footing with more populous states, like New York. The requirements for statehood were clear: The territory should not have slaves. (This was straightforward, since Nevada had at most 360 blacks.) A territory should tolerate various religious sentiments. (This was ignored, for Nevada was fashioned from a disdain for Mormons.) And, the territory should relinquish unappropriated public land. (This was simple too, for the region was vast.) The other stipulation of this Enabling Act was the state constitution had to be ratified and a copy had to be on the president’s desk (with enough time for elections in early November of 1864). That requirement was not going to be easy.

During the second state constitution convention in Carson City in July of 1864, with only three months remaining to establish the state, attendees again contended over its name, as they had done in an earlier unsuccessful convening. In this second convention, they proposed Humboldt (after the German naturalist), Esmeralda (meaning “emerald” in Spanish), Bullion, Oro Plata, Sierra Plata, and Washoe (the name of the Native American tribe of the region). Arguments were made against the name of Nevada, since there was a well-known city in California called Nevada City as well as a Nevada County. Additionally, Nevada, which meant ‘snow-covered’ in Spanish, was impractical for a land that rarely got below freezing. Consensus was formed when one voice reminded the attendees that most of the country knew it by Nevada, and it had to stay that way.

Over the weeks of wrangling at the convention, the name Nevada was settled on. On September 7, 1864, the citizens of Nevada voted 8 to 1 on their new constitution, approving it. Now, the task was to get a copy of the state constitution to the president. There was little over a month to get it to Washington. Given the means of delivery, there was just enough time.

One common way of getting a long document across the country was by boat. After a courier reached the Pacific Ocean at San Francisco, which took a couple of days, they would board a ship that headed to the Isthmus of Panama. They then crossed it by mule, and then continued on by boat up to Washington, D.C. The other way to get a document across was the stagecoach. In the 1850s, the Overland Stagecoach was created. It took over 20 days to reach the Missouri River from the West; from there a message could be carried by train, taking about a week. Nevada’s Territorial Governor Nye sent several copies of the document both by land and by sea, and waited to hear the good news from Lincoln with a proclamation of statehood.

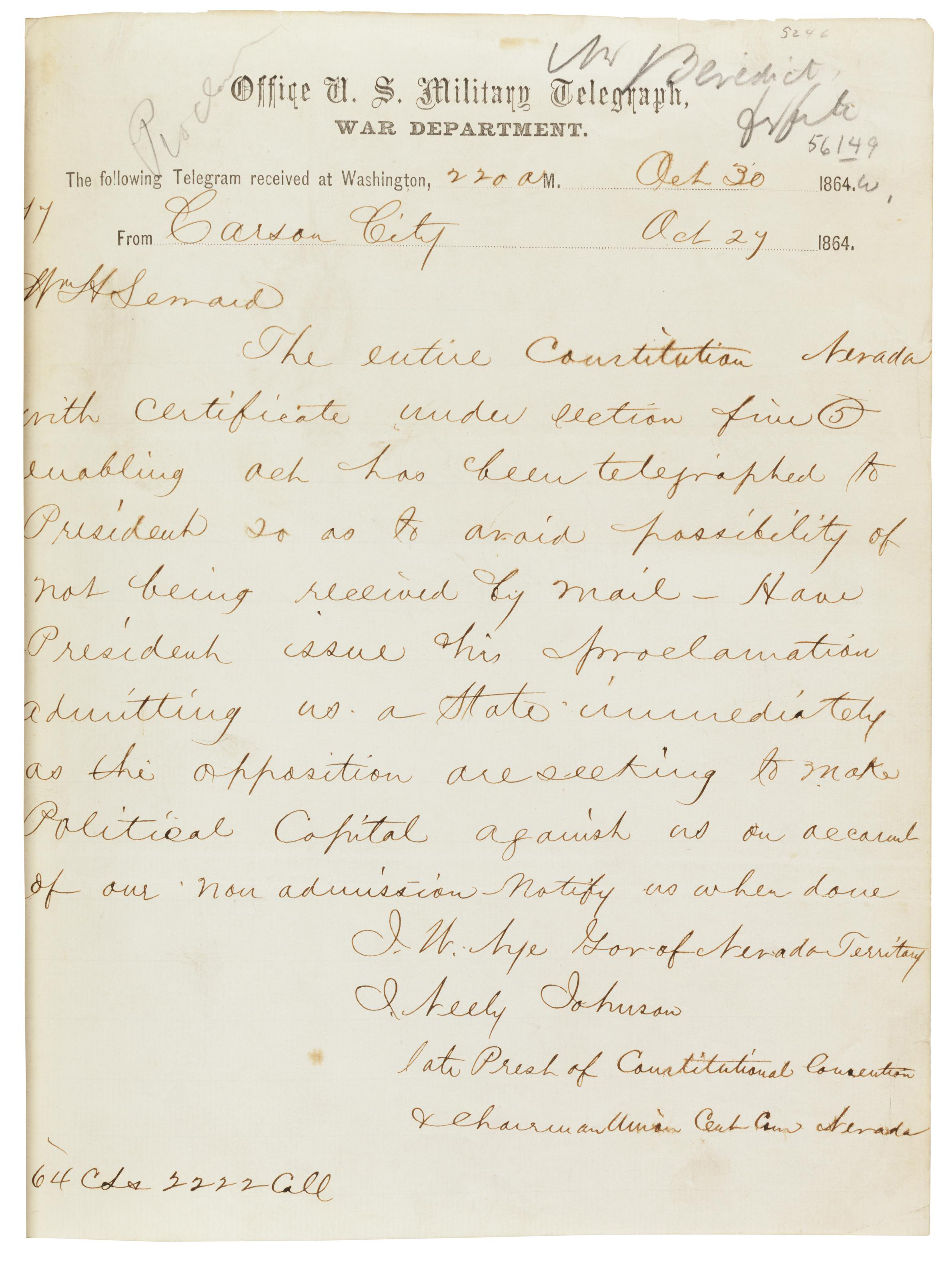

Statehood looked promising, particularly for Nye, who had great political ambitions. He preferred living on the East Coast and saw his post in Nevada as a way to launch himself into what he really wanted to be — a Senator. Nye was charismatic and known for his “winning friendly face,” but his countenance changed rapidly when a telegram arrived the evening of Tuesday, October 25, 1864. The head of the California Pacific Telegraph passed on a telegram to him, which said, “The President has not received a copy of your constitution.” The deadline for the materials was just a few days away. There wasn’t enough time to mail it to the President. If Nye was going to get 175 pages of this official document to Abraham Lincoln, he was going to have to use the new technology that was just installed three years prior — the telegraph.

On the afternoon of the next day, Mr. Hodge and Mr. Ward, the region’s best telegraphers had the job to transmit 175 handwritten pages containing the Nevada State Constitution to Salt Lake City, just over 500 miles away. In a room of Nevada’s esteemed government officials whose names would go down in the annals of history, these two men, whose first names the world would never know, were actually the most important people in the room.

The fancy cursive writing of the document had to be translated into plain dots and dashes of Morse code and then tapped into the lines. Ward began sending electrical pulses in the first shift and Hodge in the second. When Ward’s lightning-fast fingers started their dance of pat-a-tat-tat on the telegraph key, the city officials breathed a sigh of relief. The beginning of the birth of their state had begun. They retired to the inn nearby for it was going to be a long night.

The document that Hodge and Ward had to send contained 16,543 words. The message began with, “His Excy Abraham Lincoln. Official — The Constitution of the State of Nevada…,” followed by what would be equivalent to 40 single-spaced pages of text. The work was onerous, but this was Nevada’s opportunity to join the world stage, and also influence it. Opportunity knocked with the pitter-patter of telegrapher fingers.

The tapping went on for 12 hours, with Hodge, who was on the second shift, finishing at 5:30 the following morning, before the sun rose. Except for finger fatigue, there was no trouble sending the message. However, there was trouble on the receiving side. There was no direct line between Carson City and Washington, D.C., so the message had to be sent to three different relay stations on its way East where the dots and dashes were translated into words and then converted back into dots and dashes and then sent to the next leg.

In Salt Lake City, the telegrapher did not expect such a deluge and got tired after a while. One person substituted for him, but didn’t last long, and then another sat in, and then a third, before the first operator returned and finished the work. Once the dots and dashes were received in Salt Lake City, they were copied down and then sent 1,400 miles to Chicago, and then 800 miles to Philadelphia, before finally reaching Washington, D.C., 150 miles away. Thousands of dots and dashes marched across the country inside metal telegraph wires with the mission to help Lincoln abolish slavery in the land.

When these electrical impulses finally reached the last leg of their journey, they were sent to the telegraph office of the War Department. This transmission was of such importance that intelligence from the warfront was put on hold for five hours to make way for Nevada’s telegram. Hodge’s and Ward’s message took two days to get to Lincoln and the cost of sending the message was $4,303.27 ($60,000 today). Nevada’s electric constitution reached Lincoln on the evening of October 28 and he proclaimed it a state on the 30th. On the 31st of October, Nevada officially celebrated its statehood, which gave it the right to participate in the election a week later on November 8.

On November 8 of 1864, Lincoln won a second term. Nevada had made good on its promise. Two out of three of its votes from the electoral college were cast for Lincoln. (The third voter got stuck in a snowstorm.) Nevertheless, the presidential election became less critical, when Lincoln’s chances of winning due to a three-way race improved when the race settled to just two candidates. Before Lincoln got to the business of leading the nation, he paused and declared the mission of his next four years. In his inaugural address, he stated that he would not be vindictive towards the South or ignore their transgressions as other candidates had promised. He set a tone for healing, “let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds.” As president, he would serve, “with malice towards none; with charity for all.”

With this victory behind him, Lincoln now worried about the vote on the abolition of slavery act in the House of Representatives. This act had already passed in the Senate, but it had failed to get the majority of votes in the House the year before. Lincoln wished Nevada’s sole Representative, Henry G. Worthington, a swift and safe journey from the West so he could cast his single vote. Worthington arrived in time to cast his vote on January 31, 1865. The resulting count was 119 yeas, 56 nays, (with 8 abstains). The amendment passed with Worthington’s vote as one of the two that put the number of “yea” votes safely in the majority. Those two votes were precious like gold to Lincoln.

Lincoln now had all the pieces to heal the country and states began ratifying the 13th Amendment to make it into law. Nevada was the 16th state to ratify it on February 16, 1865. The amendment needed 27 of the 36 states to pass and it would get them in December of 1865.

But Lincoln would never get to see it. He was shot by an assassin and died on April 15, 1865, a few days after the surrender at Appomattox, ending the Civil War. The great architect, who drew up the blueprints to abolish slavery, would never witness the nation he helped to build. His dream was made possible by many factors, however — one of them being a very long and expensive telegram from Nevada.

Ainissa Ramirez is a materials scientist and the author of “The Alchemy of Us.” Twitter: @ainissaramirez

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com