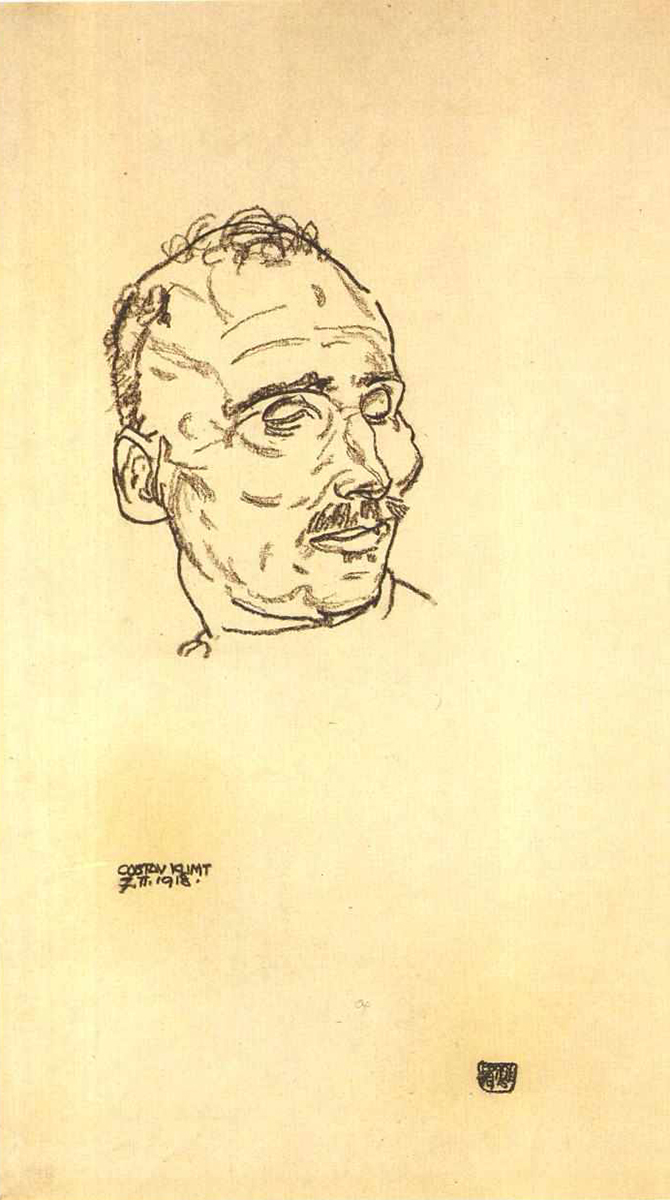

On Feb. 7, 1918, the artist Egon Schiele, then 27, once again looked to his mentor, Gustav Klimt, to be his muse. But this time, Schiele had to visit the morgue of Allgemeines Krankenhaus, the Vienna General Hospital, to make his drawings of the renowned painter. The day before, Klimt had died of a stroke that many historians believe was a result of the flu. Schiele’s visit resulted in three haunting drawings of a deceased Klimt’s head, showing his face deformed from the stroke.

That same year, Schiele began working on a painting, The Family, which was meant to be a portrait of himself, his wife and their future child. But before he could finish the piece, his wife, who was six months pregnant, died of the flu. Three days later, Schiele’s life was also taken by the flu.

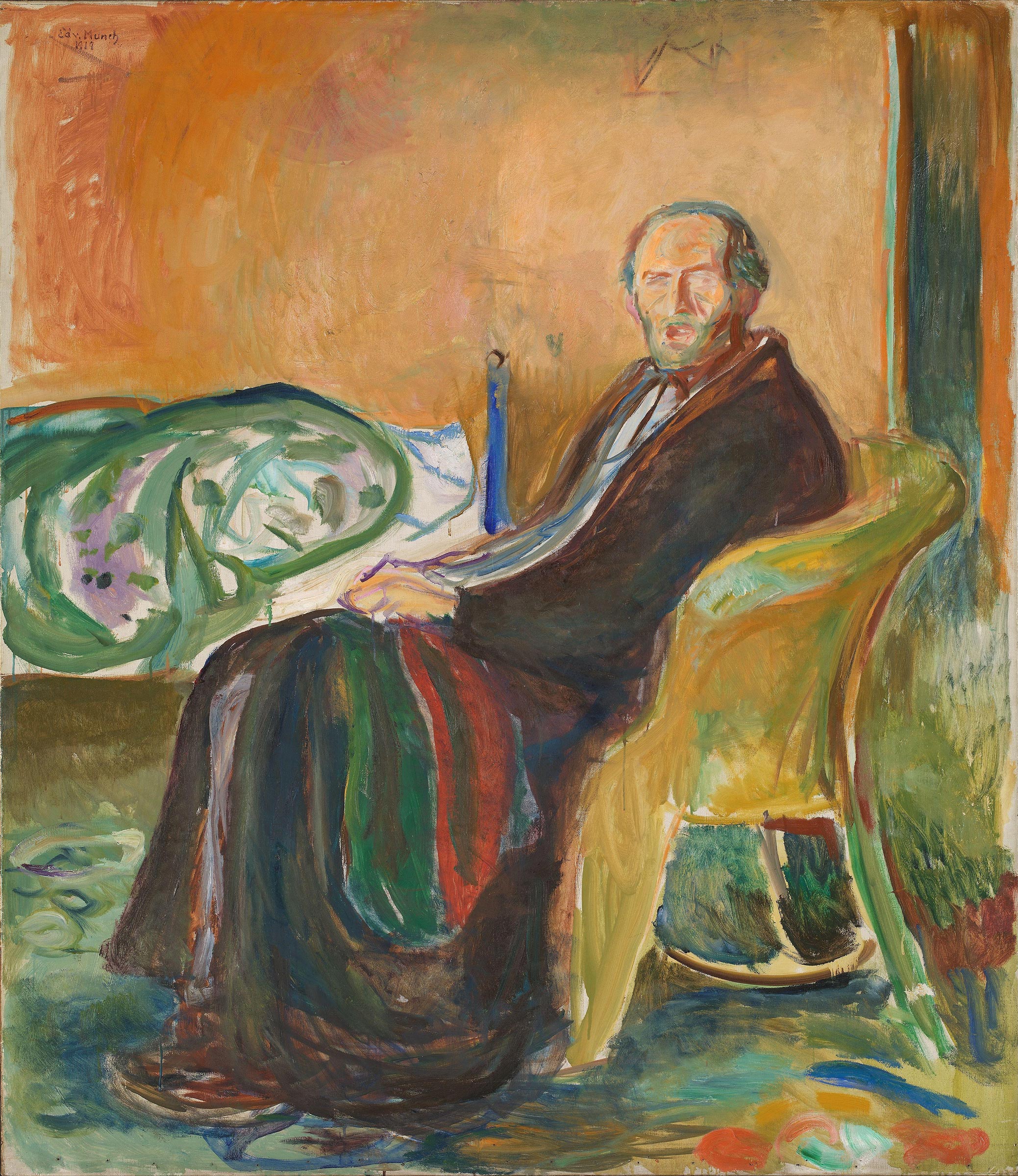

Norwegian painter Edvard Munch also found inspiration in the disease. The artist made Self-Portrait With the Spanish Flu and Self-Portrait After the Spanish Flu, detailing his own experience contracting and surviving the illness. These paintings, characterized by Munch’s obsession with existential drama, speak to feelings of trauma and despair that were widespread amid a pandemic that killed at least 50 million people. “Illness, insanity, and death…kept watch over my cradle,” the artist once said, “and accompanied me all my life.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

It could be easy to think that these works are the only famous examples of the impact of the 1918 flu on the world of western fine art. Though the ongoing fight against COVID-19 has drawn renewed attention to the pandemic of about a century ago, the influenza pandemic has long been largely overshadowed by World War I—in public memory as well as contemporary thought—even though the flu had a higher death toll. In light of wartime efforts, news about the initial spread of the 1918 flu was played down in many places. “Do not worry too much about the disease,” wrote the Times of India, in a country where 6% of the population ended up dying from the illness. In addition, many artists were sent to war during this time or died prematurely of the flu themselves.

But the flu did not go unnoticed by artists. Rather, the outbreak magnified the absurdity of the moment, according to art historian Corinna Kirsch. For many, World War I and the flu combined with political upheavals (such as the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of newly-formed communist governments) and social issues (such as gender and income inequality) to create a perception of the universe as chaotic and hopeless. A sense of meaninglessness spread, and people started to lose faith in their governments, existing social structures and accepted moral values. Everyday life felt ridiculous. The art movements that came out of this period explored this hopelessness, tried to fight against it and showed the ways in which everyone was trying to cope.

The Dada movement in particular seized on this absurdity as inspiration. The Dadaists wanted to create a new form of art, one that could replace previous notions altogether. Collage became a popular medium at the time; “many artists were dealing with the modern era and the horrors of war through strategies of cutting, reassembling and remixing,” explains Kirsch. One 1922 piece by Hannah Höch, the only woman who was part of the Berlin Dada group, parodied a traditional German guest book by collecting Dada sayings rather than the typical well-wishes from house guests. One saying included in the piece was from the poet Richard Hülsenbeck: “Death is a thoroughly Dadaist affair.”

George Grosz, another Dada artist, painted The Funeral around 1918, depicting distorted human figures haphazardly overlapping one another in what appears to be a never-ending street, surrounded by nightclubs and buildings. In the middle of the crowd is a skeleton perched on top of a coffin drinking from a bottle. “In a strange street by night, a hellish procession of dehumanized figures mills, their faces reflecting alcohol, syphilis, plague … I painted this protest against a humanity that had gone insane,” Grosz later said of his hellscape.

Though Dadaism was mostly nihilistic in its approach, “there was also a utopian impulse at work with many artists who wanted to create an entirely new world and revolution,” says Kirsch.

With this impulse in mind, architect Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus School in Weimar, Germany, in 1919. The Bauhaus aimed to bridge art and design, training students to reject frivolous ornamentation in order to create art objects that were practical and useful in everyday life. Marcel Breuer, who started at the Bauhaus in 1920 and eventually taught there, designed furnishings that historians believe were influenced by the flu. In contrast to the heavy, upholstered furniture that was popular at the time, Breuer’s minimalist pieces were made of hygienic wood and tubular steel, able to facilitate cleaning. Lightweight and movable, works like the designer’s bicycle-inspired Wassily Chair and Long Chair met modern sanitary needs by being easy to disinfect and rid of dust build-up.

“The rise of modern architecture and design in the 1920s was inextricably linked to the prevailing discourse on health and social hygiene,” says Monica Obniski, curator of decorative arts and design at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art.

To other artists dealing with the horrors of the time, abstraction was a way to escape reality. “Abstraction became a defining sense of that moment in time. There was a definite relationship [between] non-objective, non-realistic art and the horrors of what was going in the world,” says Jeff Rosenheim, Curator in Charge of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Photographs. This was seen in many paintings and photographs made during the time. [View of Rooftops], a 1917 photograph of a desolate New York City scene, made by Morton Schamberg, is one example of this. The photograph, shot at an oblique angle, abstracts the cityscape in a Cubist manner and lacks any signs of human life. Schamberg died of the flu in 1918.

Further, in 1917, Fountain was unveiled under the pseudonym R. Mutt. The work consisted of a standard urinal, signed and dated, and thrust the art world into discussions of what was and wasn’t to be considered art for years to come. It is widely believed that “R. Mutt” was Marcel Duchamp, but the subject has been up for debate. Art historian Michael Lobel argues that R. Mutt could also have been Schamberg. We aren’t able to know for sure because of the artist’s premature death from the flu. “Schamberg’s relatively early death not only cut short his career but also means that we have little to no recorded testimony from him on these and related matters. In his case, then, the pandemic registers mostly as a telltale absence in our account of the period,” Lobel has written in Art Forum.

![Morton Schamberg's "[View of Rooftops]," 1917](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Morton-Schamberg-view-rooftops.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

Just as the 1918 flu pandemic was an inescapable part of the zeitgeist of the time, the coronavirus pandemic has already become so today. Though we might not know exactly how COVID-19 will affect art and art movements to come, the visual culture has already shifted.

“Photographers discovering empty streets and how our cities look without people show a kind of sad beauty to these urban metropolises around the world,” says Rosenheim. The empty cityscapes being captured and shared “aren’t depicting the pandemic, but the effects of isolation and emptiness, psychologically.” Others have argued that, as a result of the quarantine, nude selfies have become high art.

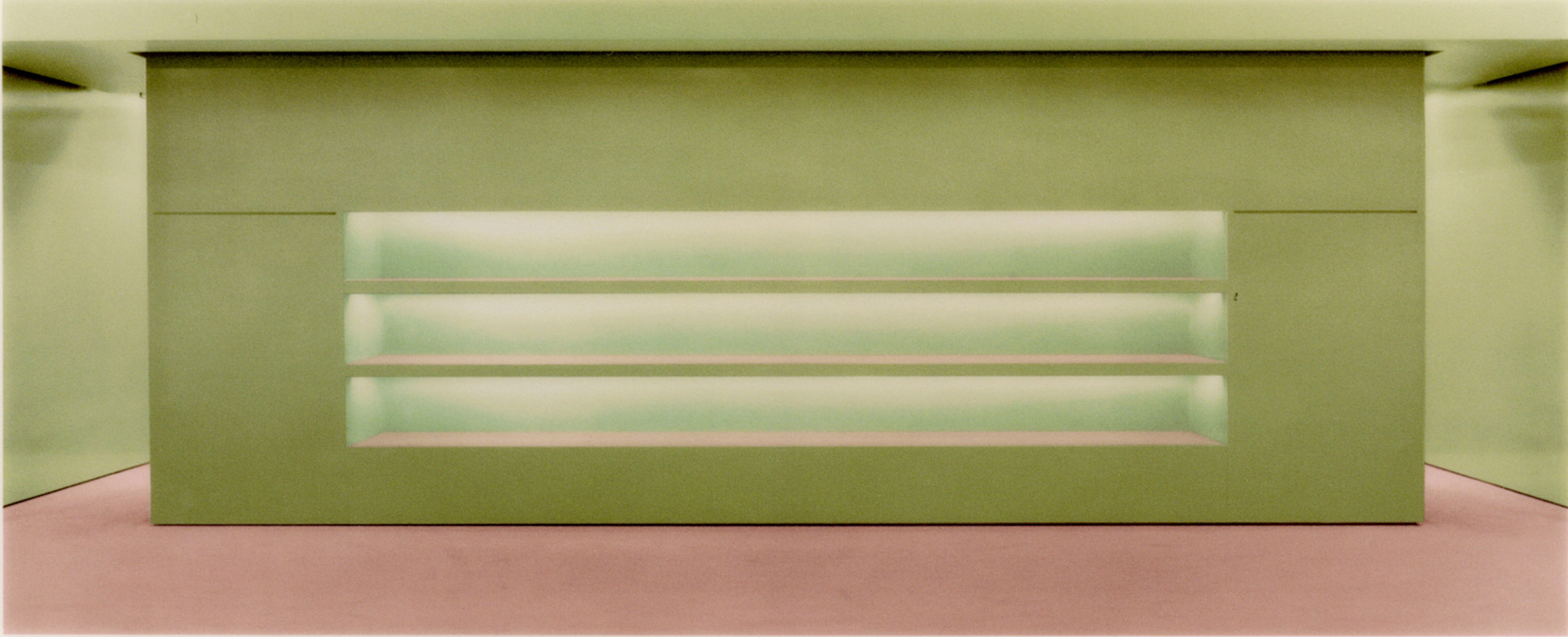

As was the case in 1918, the pandemic is just one part of a larger mood that predated the disease. Isolation, stillness and the impacts of consumerism were already themes being explored through art in recent decades. For example, Andreas Gursky’s 1996 photograph Prada II shows a display case that is completely void of product and lit with sterile, fluorescent lights — an image that now calls to mind news photos of store shelves left empty amid the pandemic. Gregory Crewdson’s early 2000s “Beneath the Roses” series captures with a surreal ghostliness the desolate corners of small towns, evoking the urban loneliness of Edward Hopper’s paintings, which are being disseminated widely on social media today.

These works were created before the novel coronavirus swept the world, but they speak to the current moment — proving that, as was the case in the past, Rosenheim says, “we don’t need a pandemic to create chaotic, psychologically traumatic imagery.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Write to Anna Purna Kambhampaty at Anna.kambhampaty@time.com