The planet had no way of knowing that an entire nation of 205 million people was waking up on April 22, 1970—the first Earth Day—planning to rise in its defense, but it nonetheless cooperated in the effort. The temperatures were generally mild and the skies generally clear in the East and West, and it was sunnier and warmer still through most of the South and Plains states. The Pacific Northwest was expecting some showers, but the Pacific northwest was always expecting showers.

Many businesses had adopted the Earth Day message and a lot of them pledged to donate money or stage events in support of it. That morning’s issue of the New York Times included a full-page ad taken out by Seventeen magazine—whose audience was made up of just the kind of kids and teens the Earth Day organizers were hoping to reach. It featured a moody picture of a young couple walking along a beach, with text that read, “Today—Earth Day—we salute millions of earnest young people who have accepted the challenge of seeking solutions for our environmental ills. Having reached the moon in the Sixties, perhaps in the Seventies we shall rediscover the earth!” If there was something a little insincere in all of the corporate enthusiasm—an attempt to cash in on a good cause and, in effect, take a free ride on the work of all those earnest people—it still showed that on the side of the environment was the right place to be.

In city after city, community after community, people turned out. Events were staged on 1,500 campuses and in 10,000 schools, with speeches, marches, community clean-ups and even teach-ins pressed for by Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, an Earth Day organizer. Boston school children picked up cans and bottles in vacant lots. Sacramento students did the same and even did the heavy work of gathering up abandoned tires and carting them off for proper disposal. More than 1,000 students from Cleveland State University picked up trash from around the city and loaded it into garbage trucks that had been made available for the day. In New York, students from a Brooklyn high school cleaned the beaches that abut the borough. Students in Manhattan picked up trash in a park on the island’s upper east side, next to the East River and near the Mayor’s mansion, an area that was meant to be scenic but was spoiled by rubbish. College students gathered in subway stations along the dirty, neglected Lexington Avenue Line and washed the windows of the trains when they made their stops.

Inevitably, with college students involved and the high-spirited energy of the 1960s uprisings in play, some of the protests became equal parts theater. Students at Florida Technological University held a trial for a Chevrolet, found it guilty of poisoning the air, and sentenced it to death—though despite their efforts to destroy it with a sledgehammer, they couldn’t quite carry out the execution. Students at the University of Minnesota held a solemn ceremony in which they buried an internal combustion engine. Students in Cleveland paid tribute to the city’s founder, Moses Cleaveland, with one rowing to more or less the spot on the once-clean, now-filthy Cuyahoga River where the long-ago explorer was said to have come ashore. The student then looked around, declared it too dirty a place to build a colony, and rowed back off.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In Denver, where the high elevation and thin air increases the destructive impact of automobile exhaust, high school students pedaled bicycles to the state capital as a symbol of protest against cars. Nelson spoke at a Denver teach-in and deftly connected the environmental movement with the anti-war movement. Environmental degradation, he said, “is a problem perpetuated by expenditures of tens of billions of dollars a year on the Vietnam war, instead of on our decaying, crowded, congested, polluted urban areas that are inhuman traps for millions of people.”

In Washington, D.C., students marched on the Department of the Interior and gathered on the Mall near the Washington Monument. Earth Day organizer Denis Hayes spoke there, also connecting the environmental movement to the Vietnam war, but doing so with the stridency and passion of an activist, compared to the more measured tones of Nelson, a politician. “Even if that war were over tomorrow,” he said, “we would still be killing this planet. We are systematically destroying our land, our streams and our seas. We foul our air, deaden our senses and pollute our bodies.”

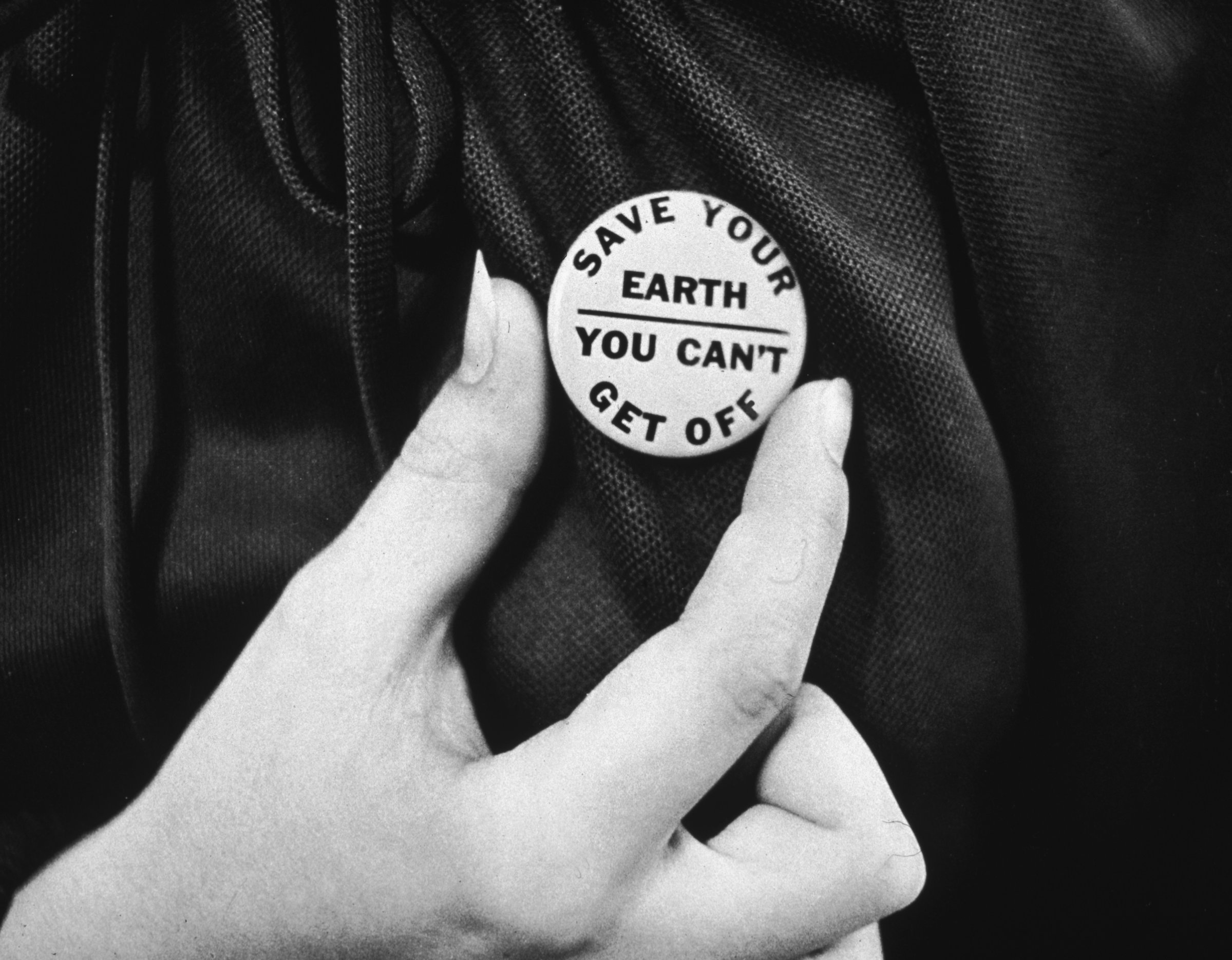

New York City, determined—as it so often is—to do things bigger, better, more ostentatiously than any other place in the nation, delivered on that effort. Mayor John Lindsay closed Fifth Avenue from 14th Street to 59th street, giving the boulevard over to marchers and speeches. Bunting in orange and blue, the city’s colors, hung from lamp posts, and balloons stamped with environmental slogans were distributed. That the balloons if not the bunting would surely enter the waste stream later that day—creating mounds of garbage that were just one more part of the environmental problem—seemed, at least at the moment, less important than conveying the environmental message.

Downtown in Union Square, near New York University, booths were set up promoting various parts of the environmental cause—curbing air pollution, controlling population, building cleaner cities. At least 100,000 people moved through the square that day, many of them stopping at the booths to learn more about the various issues. Con Edison, the city power company, which was long criticized for its poor environmental record, feared protests and even violence and while it remained open for business—a power company could hardly shut down—it kept its doors locked and stationed security guards at each one. But there was no violence; these were not the angry protests at the Democratic Convention in Chicago from two years earlier. This was a happy—if deeply worried—statement of love for the planet.

The demonstrations and celebrations kept going all day, all over the country, ending well after nightfall, which arrived, as it always did, sequentially, with the turning of the newly appreciated Earth bringing darkness first to the Eastern time zone, then to the Central, then to the Rocky Mountains, and then to the Pacific. The question then became, what would America do when Wednesday turned to Thursday, when April 22nd turned to April 23rd, and the nation woke up to a world that was no less dirty than it had been the day before.

From RAISE YOUR VOICE by Jeffrey Kluger, published by Philomel Books, an imprint of Penguin Young Readers Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Jeffrey Kluger

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com