I often tell my students you don’t want to be interesting to doctors or historians. Yet here we are, in interesting times for both. The medical field will spend the next decades studying this coronavirus and COVID-19. Epidemiologists, doctors, researchers and even hospital administrators are already busily studying how this pandemic has happened, what it is doing to our bodies and how to respond. But historians, while busy now putting current events into historical context, will not begin actively studying our times for another 30 years or so. And they will need our help.

Future generations of historians, who haven’t lived through this moment, will be key in studying it. By the 2050s, they will have more perspective on the causes and effects of this moment, as well as plenty of sources—government documents, transcripts of press conferences, newspaper opinion pieces. They will have more public sources too. While most of our Facebook debates will likely be lost to time, at least some of our tweets will be saved by the Library of Congress for posterity. But these public sources will be just snippets of our present. Historians will need other sources to be able to understand, and learn from, our times. They will need more to ensure that the stories that are so often lost to the past are told. Oral histories and personal journals will be vital tools to take their understanding beyond the headlines.

When I first began studying the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) of World War II in the 1990s, it was just 50 years since the end of the war and the women were in their early 70s. After researching the government sources and other traditional evidence about their work flying for the U.S. Army Air Forces during the war, it was clear an important part of the history was missing that only the women themselves could tell. Oral history has evolved out of the oral traditions of old, pre-written-word cultures. Beginning in the 1960s the practice of oral history has been professionalized, with thoughtful historians carefully defining principles and best practices for practitioners. Oral histories, from the slave narratives of the New Deal era to experiences during Hurricane Katrina, add a richness to historical understanding unlike any other source.

Some of the most important questions I had for the women pilots were about their motivations. The specifics of their flights and such were available in other sources, but flying military planes was dangerous; 38 of the women died during the war. Why did they do it? How did they feel and what did they do when the WASP were disbanded in December 1944, nearly a year before the war ended? What did they do after the war? What had they wanted to do? Oral histories can help answer questions where other sources don’t exist and, importantly, get perspective. There is little doubt that historians in 2050, whether professionals or school kids doing their National History Day projects, will be calling for oral histories of those who lived through 2020.

But oral histories, collected 30 years from now when we all know who survived and who was lost, who is blamed and who are the heroes, while incredibly valuable, will carry their own taint of bias. Interviewees often, even subconsciously, shape their responses in part around the interviewer. They want to look good to the person asking the questions, to please them with the “right” answers, thus the herculean efforts of professional historians to earn enough trust that their interviewees will be honest. This inherent weakness of oral histories is why we must help historians of the future by creating corroborating sources now.

Personal journals can be vital primary sources. While we all cope with the mental health challenges in these anxious times, health professionals say journaling can help reduce anxiety, stress and symptoms of depression. In addition to being good for our health, journals will help historians as they try to understand our lives today.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In 1937 a group of scholars in Britain began the Mass Observation Project, asking regular diarists to observe their own lives and the world around them. The project continued and grew throughout the war years and to say the observations have become invaluable is not an overstatement. In my own work on the WASP of WWII, I wanted to corroborate the memories I’d learned about through the oral histories, so I turned to the women’s letters home and especially their diaries. The letters have stories of their own to tell, revealing interesting differences whether they were written home to mom and dad or to a best friend, but it is the diaries that reveal the most.

The young women pilots wrote for themselves both to relieve stress and to help remember their experiences flying within the continental United States during war. Through diaries we learn the writer’s hopes and fears, things that annoy them, little joys. News often made it into the journals of these women pilots, sharing with us their understanding of the yet-undetermined path of the war. The diaries reveal, too, how the writer changes over time. Things that worried them early on become second nature, events that they mention in passing become life-changing. Their opinions, hopes and dreams change over time.

It is sometimes hard to imagine, but we have always been a part of the past. Now we are part of our own historical moment in time, a period that historians will debate for decades, even centuries to come. Our chance to control some of that narrative is in our hands. If we don’t want to be forgotten we must write down our own experiences and thoughts. We should write first for ourselves — an honest release at the end of the day. We should not try to guess what future historians want or need; they will develop their questions on their own. We should write our own individual truths, as best we can. Someday, as WASP Elaine Harmon told me she experienced as the war ended, we will suddenly walk around the streets again, the burden of worry and fear lifted from our shoulders. When that day comes, we will want to be able to look back at how far we have come and celebrate one another — together, knowing the story of our experience will live on.

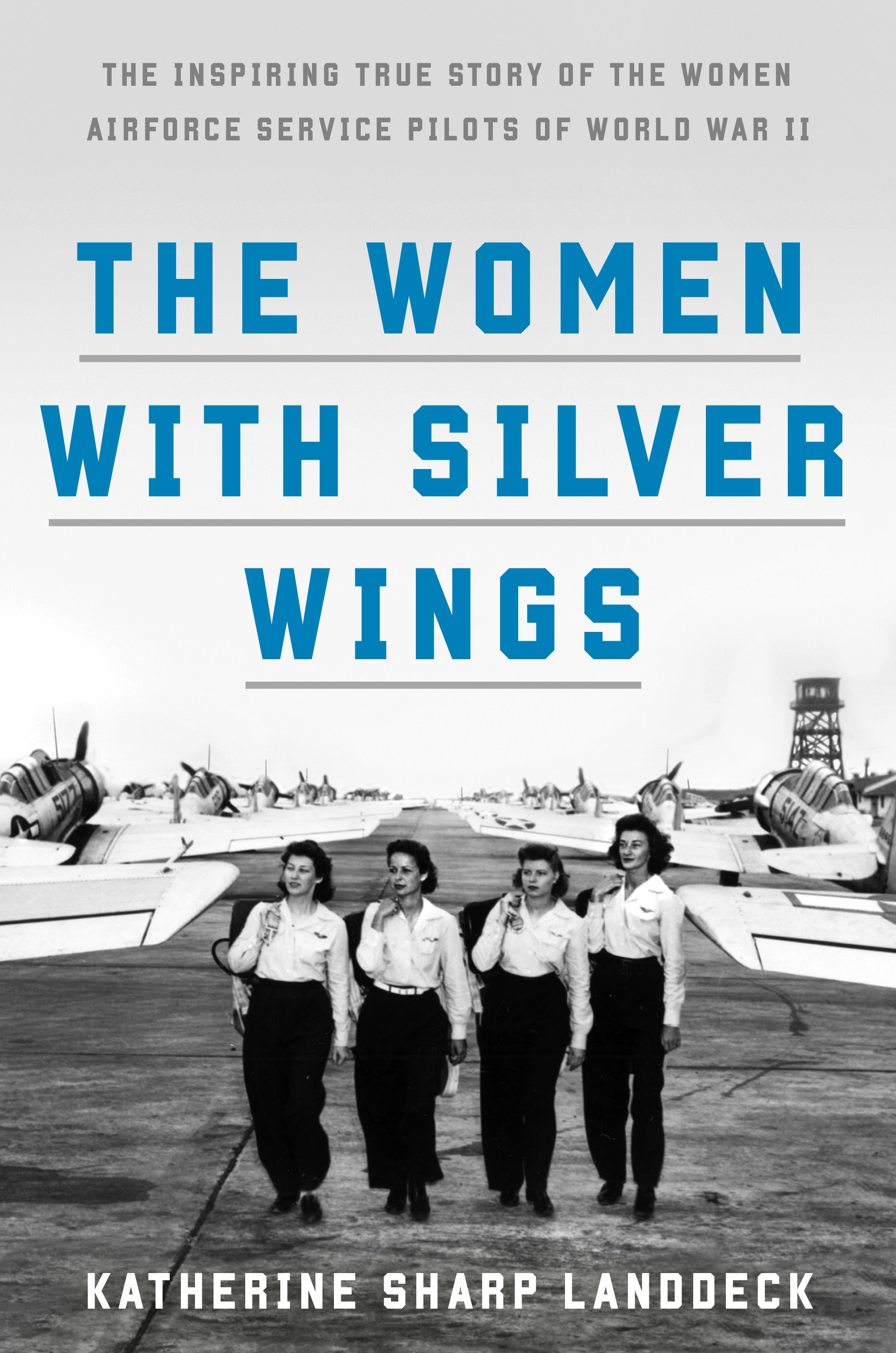

Katherine Sharp Landdeck is the author of The Women with Silver Wings: The Inspiring True Story of the Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II, available now from Crown.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com