Casey and Adam Donner each own a small business in Lincoln, Neb. She is a make-up artist, helping brides get camera-ready on their big day. Her husband employs 30 people at his construction firm.

Both businesses were churning along when the novel coronavirus crashed on U.S. soil, bringing much of the economy to a standstill and sending 22 million Americans and counting onto the unemployment rolls. Casey Donner’s services — as with salons, barbers and tattoo parlors in the state — were suddenly no longer allowed to keep operating. Construction is still permitted in Nebraska, so Adam Donner has managed to keep his crews working. But it’s scary to keep making plans when there’s no telling what the economy’s going to look like in six months, he says.

Earlier this month, the Donners both successfully applied through their local bank for federally backed small-business loans bundled in March’s $2.2 trillion stimulus package. If they keep their doors open and their employees on the books through the pandemic, the principal on the loan will be paid by the government; in other words, it’s potentially free money. The $349 billion program was designed as part of the stimulus package to give firms some hope of recovery if they’ve been shuttered for health reasons, or if they’ve kept the doors open in the face of an economic recession. “It’s a blessing because we can keep going,” says Adam Donner, 39. “This is a shot-in-the-arm for us, and it was pretty easy to get.”

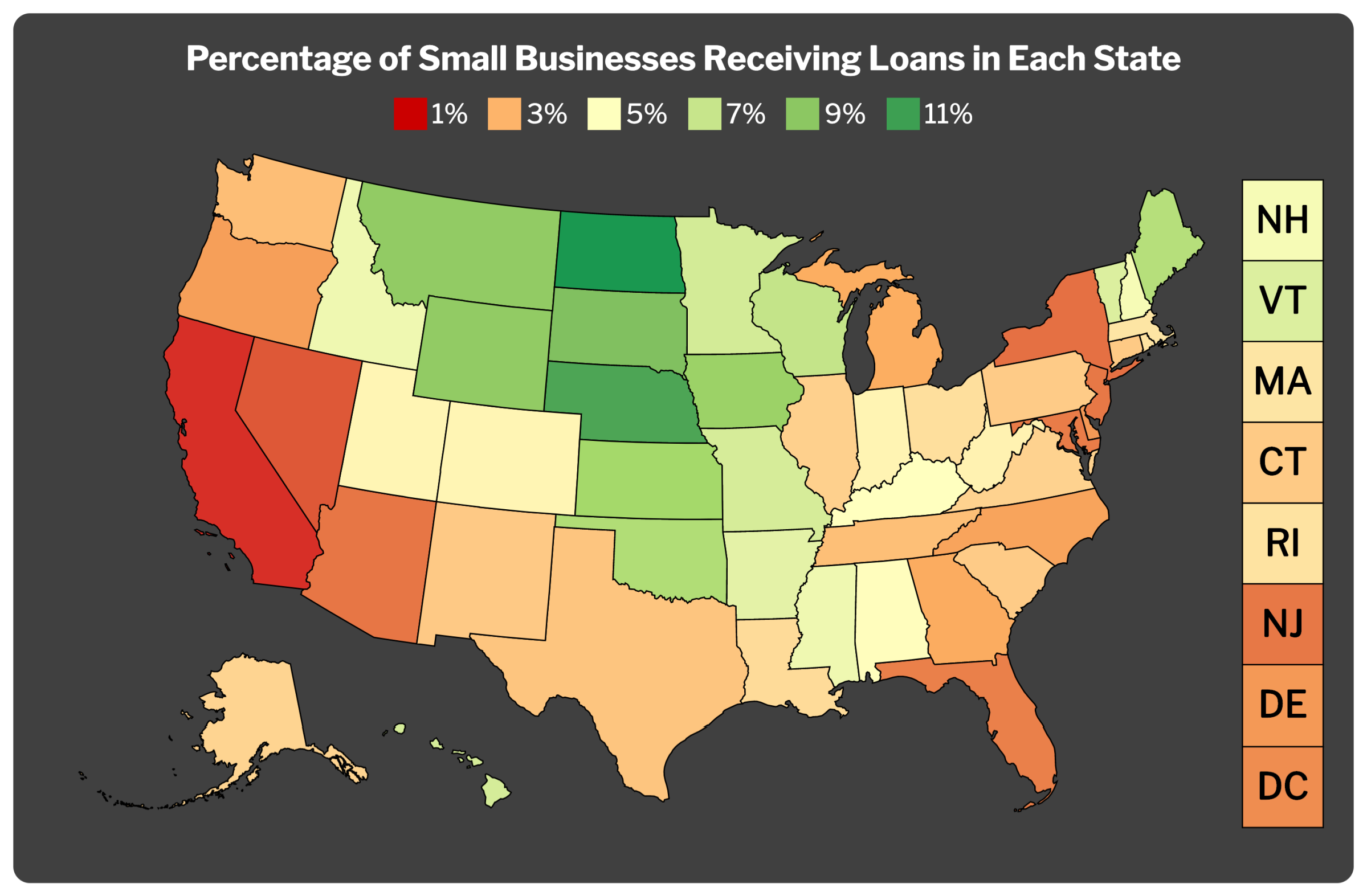

The Donners’ geography may have given them, at least for now, a leg up. Small businesses in the Midwest are drawing an outsized share of the small-business lending program designed to keep their lights on, a TIME analysis of lending patterns finds. More than any other region, the stretch between North Dakota and Kansas in the west and heading eastward toward Ohio has outpaced the coasts in borrowing per small business. The average small business in Nebraska was on track to be five times as likely to get a small business loan under the program than its peers in New York, the current epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak.

While the biggest states have predictably received the largest dollar amounts from the program, with the most money flowing to Texas and California, examining the percentage of small businesses receiving loans in a state paints a very different picture. In Nebraska, 18,565 out of about 175,000 small businesses, according to the Small Business Administration’s 2018 figures, received loans, or 10.7%, second only to North Dakota nationwide. In New York, by comparison, that figure is 1.9%, third-to-last ahead of California and Nevada.

The Paycheck Protection Program was not designed to help businesses in communities grappling with the worst coronavirus outbreaks, but to mitigate the economic effects of a crisis rippling throughout the national economy. But the uneven distribution of the program’s funding has followed a pattern in which a disproportionate amount of money has been heading to places where fewer people are sick at present, while small businesses in the worst-hit states, like New York and New Jersey, have not been able to access the fund at anywhere close to the same rates.

It’s impossible to say definitively why Midwestern businesses have been so successful getting these loans. To access the program, small businesses lodged applications at participating banks, who processed the loans and moved the money out the door. At the same time, banks looped in the the Small Business Administration in Washington to let them know how much the federal government was now guaranteeing. The places hit hardest by the virus may simply have been too pre-occupied by the public health crisis to figure out how to access the program. Another factor may be that Midwesterners are already amenable to working with the federal government, given their experience accessing farm subsidies and disaster relief after floods and tornados. Then there’s the lingering reality of the 2008 economic crisis: rural America has lagged behind the nation’s cities in terms of recovery, and economic insecurity is never far below the surface. That may have motivated small-business owners to act fast.

But the most common explanation offered by scholars and laymen alike is that bankers in smaller Midwestern communities may have simply been more familiar with their neighbors’ needs and helped their clients prepare the paperwork early. “We typically expect the rural nature of smaller states to be disadvantageous in many ways, but it seems in this case, perhaps less population density and greater density of acquaintanceship actually allowed for a more nimble, personalized and efficient response,” says Elizabeth Legerski, an associate professor of sociology at the University of North Dakota.

In other words, knowing your neighbors may have paid off.

Take, for instance Barry Schweer. He is a branch president for Nebraska’s 13-location Heartland Bank. Even before ink was dry on the March 27 law authorizing the guaranteed loans, Schweer was banging on doors and filling up inboxes to his business customers to alert them to the program that was coming online. He knew the mom-and-pop shops in his communities would need help. His is the 13th largest Nebraska bank but was able to fill 70 loans in the space of two weeks.

“In our-sized communities, these small businesses are definitely the bread and butter of the bank,” Schweer says. “Once we knew the program was coming out, phone contacts, text contacts — whatever it was — we were making contacts with our customers.” He still has four or five applications on his desk that didn’t get cleared before the program ran out of cash on Thursday, but he’s hoping Congress approves a proposed a second round of cash that helps those left be among the first he dashes off to Washington.

Union Bank & Trust, a privately held Nebraska lender with 38 locations, kept its loan department staffed 24 hours-a-day when the loan program started. In the end, the bank — ranked according to its assets at spot 202 by the Federal Reserve — processed the second largest volume of loans nationally over the first few days that applications were open and got more than 2,000 businesses help before the money dried up. “We knew a large volume was coming in short time. We rallied our employees around helping our clients,” says T.J. Casady, a bank vice president who marshaled the small-business lending program. “There’s a real personal relationship that many of us have with our clients. They’re our neighbors and they’re our friends.”

But despite the good-neighborliness, there remains a deep-seated anxiety over the economic future of the shuttered strip malls and main streets in this part of the country, even if they do get loans. “I’m not positive that they’ll all survive, I mean, even with this help,” says Schweer.

A trade war with China set back agriculture exports from the Midwest. Cheap energy, too, has tanked economies that weathered the 2008 recession through valuable reservoirs of natural gas discovered on the plains. While Wall Street has been booming in recent years, the last month has seen a decade of job gains wiped out with no sign of end. March’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rates were scattershot for the region, with North Dakota reporting the nation’s lowest unemployment rate, at 2.2%, to Ohio’s 5.5%. Nationwide, the number was 4.4%.

The Midwesterners’ awareness of its hard economic realities may have contributed businesses owners’ successfully accessing more loans, says former Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, who has has spent years studying the region as potentially fertile ground for fellow Democrats to campaign and win. “If you look at those states that are now at the highest percentage [of small-business loans], they represent places that already have economic stress, she says. “Rural America has never shared in the prosperity post-recession.”

Not everyone buys that theory. “I find it hard to believe that those states’ small businesses were somehow faster to apply than plenty of very smart small business owners in cities and metro areas, so I’m skeptical it’s something inherent to the region,” says Democratic strategist Isaac Baker, a former aide to Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner and Barack Obama’s 2012 re-election effort.

Either way, the political importance of small businesses in this part of the country is not likely to have been lost on President Donald Trump, who signed the stimulus package into law last month. Among the states that fared better than the national average in securing loans, 11 are expected to be competitive when Trump tries to win a second term in November.

Trump was already campaigning on the small business help this week and blaming Democrats for not approving another $250 billion to top off the fund as the program money ran out. “Democrats are blocking additional funding for the popular Paycheck Protection Program,” he tweeted on Thursday. “They are killing American small businesses. Stop playing politics Dems!”

For folks like the Donners, the politics is secondary to their small businesses’ needs. In these uncertain times, every dollar is a life preserver. “Everyone I know applied,” Adam Donner says. “When the government offers money like that, you take it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com and Chris Wilson at chris.wilson@time.com