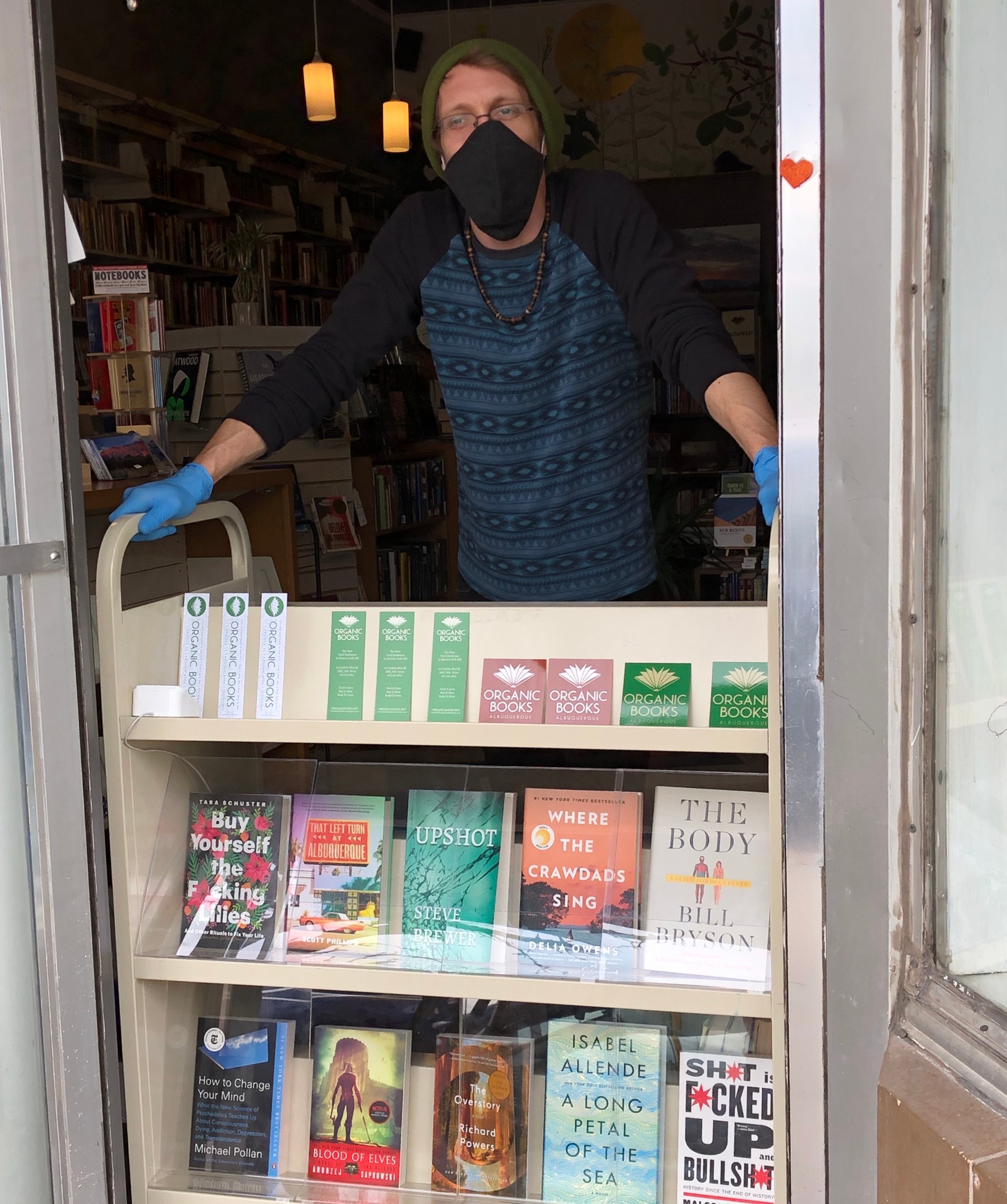

Earlier this winter, the year-old bookstore Organic Books in Albuquerque, N.M., was finally finding its footing. “We were establishing ourselves in the community, and going gangbusters,” Kelly Brewer, the store’s co-owner, tells TIME. Her cautious optimism was reflective of the prevailing mood among many independent bookstores across the country. Sales were increasing; events were selling out. New stores from San Angelo, Tex., to Hoboken, N.J., were opening and becoming cultural anchors in their communities.

“Then, boom, the hammer fell,” Brewer says.

When COVID-19 forced non-essential businesses to close across the country last month, independent bookstores shuttered their doors and feared the worst. Already, these stores operated on slim margins and in the shadow of Amazon’s dominance. A prolonged period of closure might not only shift consumer habits toward online buying, but also erode the communities that they had worked so hard to foster.

As these bookstores remain closed, however, an online movement has emerged to bolster their chances. One organization in particular, Bookshop.org, has become a unifying force, raising hundreds of thousands of dollars for local stores desperate for an alternate source of revenue.

As booksellers adapt to online business models in a fraught global economic moment, the coming months of transition could determine whether independent bookstores survive. Owners say that it’s not just their solvency at stake — but also the role of books in American communities.

“If Amazon really wipes out independent bookstores, the end result isn’t just going to be that they get all the book sales in the world,” Andy Hunter, the founder of Bookshop.org, tells TIME. “It’s going to be that people read fewer books.”

‘It’s like taking a shot at the Death Star’

In the years since Amazon opened its online bookstore in 1995, the books market has evolved. Major chains, like Borders and Book World, have disappeared. Amazon now accounts for more than half of all book sales, and three quarters of all books or e-books bought online, according to Codex, a book audience research firm. Over the last five years, Amazon’s market share of all books has jumped 16%.

Hunter, publisher at Catapult and co-creator of the website Literary Hub, watched these developments with increasing concern. A decade ago, he began to formulate a pie-in-the-sky idea to create an independent, nonprofit challenger. “It’s like taking a shot at the Death Star,” Hunter says. “You have to take your shot, because otherwise you know what’s going to happen: eventually, Amazon is going to be the only player.”

Hunter’s idea was to create a site where customers could buy books from a wholesaler and direct the profits to independent bookstores. Most independent bookstores have loyal fan bases but small inventories and limited shipping capabilities, whereas Amazon, Hunter says, sells books at a loss in order to increase their market share. (Amazon did not respond to requests for comment.) By centralizing resources to a shared hub, Hunter imagined he could provide customers with prices and delivery speed comparable to Amazon’s while still sending money to their favorite bookstores.

The idea was met with derision. “Everyone thinks you’re insane if you think you can compete with Amazon in any way,” Hunter says. “I’ve had people say to my face, ‘You’re going to fail.’”

But last year, Hunter’s idea gained the approval of the American Books Association, and he began to work on creating Bookshop.org, a b-corporation (one whose purpose is to balance profit with serving the public good). With a team of five people, the website launched at the end of January and started modestly filing orders for about $4,000 worth of books a day.

When a customer elects to buy a book through a specific store on Bookshop, 30% of the sale (the entire profit margin, according to Hunter) goes straight to that store. For transactions that customers don’t mark for a specific shop, 10% of the sale is distributed evenly among the participating bookstores, allowing those with less of a preexisting following to reap some of the profits. All the orders are fulfilled through the wholesaler Ingram. Bookshop prices titles at a few dollars more on average than Amazon, with Hunter banking on the same conscious consumerism movement that inspires customers to buy hybrid vehicles and organic produce to keep the site competitive.

$850,000 and counting

The onset of the global pandemic has silenced skeptics of Hunter’s idea. As bookstores closed and began looking for ways to continue making money, Bookshop became an un-ignorable safety valve, especially as Amazon has reportedly been deprioritizing books and delaying their shipments.

Since March 1, the number of stores selling through Bookshop—which is still in beta—has more than doubled, now totaling more than 560 and growing daily (the American Booksellers Association has about 2,500 member stores). These shops, leveraging their own loyal customer bases, in turn helped raise the online profile of Bookshop, whose numbers began to skyrocket. The company’s daily sales have increased by nearly 40-fold to about $150,000 worth of books; Hunter says they’re distributing over $25,000 a day to independent bookstores across the nation, and have raised $850,000 total for them so far. “We experienced about two and a half years of growth in three weeks,” Hunter says, compared to his initial growth models presented to investors.

Bookshop has had varying effects on different bookstores across the country. In Albuquerque, Brewer says that Bookshop has more than compensated for the lost in-store revenue for Organic Books. “We have a bottom line of selling 50 used books a day,” she says. “With Bookshop, if we sell 50 new books a day, that still equates for us to pay our people and keep the lights on. We are easily hitting that, and then some.”

Gee Gee Rosell, the owner of Buxton Village Books in North Carolina, says that 75% to 80% of her business now comes through Bookshop after her tourist town was completely vacated—but that the boost provided by Bookshop is more psychological than economic. “It’s not a large dollar amount, but it’s building every day,” she says.

Some sellers are less optimistic. Jake Cumsky-Whitlock, the co-owner of Solid State Books in Washington, D.C., says the revenue earned through Bookshop is greatly appreciated but isn’t close to what he would have earned through in-person traffic, and he thinks the initial swell of support it has seen in the early months of the pandemic might subside. “My pragmatic side says it’s more COVID-19-bubble based,” he says. “A lot of things have to go right for it to become a large piece of our revenue stream.”

‘Razor-thin margins’

Meanwhile, Amazon’s influence over the books industry only seems to be growing. Amazon publishes books itself, through Amazon Publishing; it serves as a digital library, through Prime Reading; its e-reader, the Kindle, dominates the e-books market. Goodreads, one of the primary online books-based social networks, is owned by Amazon, too. Publishing houses spend much of their marketing budgets on Amazon, where a book’s placement can make or break a new release. A debut author might get a second book deal based on whether or not they sold well on Amazon—so they’re more likely to promote links to buy their books from Amazon than from elsewhere.

Bookshop wasn’t designed to save bookstores from Amazon outright—Hunter only hopes to cut into 1 or 2% of the giant’s book sales. But his organization has been thrust into a much bigger role than he anticipated. In the wake of the pandemic’s onset, bookstores are suffering at unprecedented levels: since the second week of March, the charitable foundation BINC, which provides financial assistance to booksellers in need, has received over 670 applications for emergency funding. That’s more than the foundation received in total from 2012 to 2019, according to BINC’s executive director Pamela French.

“Independent bookstores operate on razor-thin margins,” Allison K. Hill, the CEO of the American Booksellers Association, writes to TIME in an email. “There’s no doubt that it will take a lot of support from customers, communities, the government and publishers to ensure that they make it to the other side of this.”

Peter Hildick-Smith, the president of Codex, thinks the pandemic could only widen the divide between independent bookstores and Amazon as new consumer habits calcify. “If stores are not able to reopen within a reasonable time frame (3 to 6 months?), this will give Amazon huge additional market share gains by default, not only immediately, but also long term,” he writes.

Building for the future

While Hunter acknowledges that Bookshop might be benefiting from a momentary bump, he and his team are working on ways to remain effective under normal circumstances.

One of those strategies is to raise awareness about Bookshop’s affiliate linking program, a lesser-known but crucial space that Amazon has dominated up to this point. Amazon forms partnerships with editorial websites, so that publications earn 4.5% from any physical book sale they generate. This has created, in Hunter’s words, “a massive funnel in which all book coverage on the internet points to Amazon.” (TIME is enrolled in an affiliate partnership program with Amazon.)

Hunter’s counter was to start his own affiliate program on Bookshop, offering 10% of a sale to publications—more than double Amazon’s deal. Over the last two months, the New York Times, Vox and Conde Nast publications have added Bookshop to their “Buy” buttons, prompting consumers to make the choice for themselves; a representative for Buzzfeed said that they switched to linking to Bookshop over Amazon entirely. A representative for Indiebound, a website that connects readers with independent bookstores, also said that its own affiliate program would merge with Bookshop’s this year, providing more exposure and revenue potential for the program.

As Hunter hopes to redirect some of the online cash flow from Amazon’s coffers to independent shops, booksellers themselves are realizing they must change their mindsets about the potential of online community. Many stores are currently testing virtual events, like author meet-and-greets and book clubs. Solid State, for example, is hosting live author discussions and readings on Instagram and Facebook. They also continue to run their monthly book club, Lit on H Street, online—April’s pick is Helen Oyeyemi’s Gingerbread.

And other organizers are joining Hunter in the fight to support indies. Libro.fm, a challenger to Amazon’s Audible which also sends its earnings to local bookstores, has seen a 300% increase in membership from February to March. BINC has distributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to independent booksellers in need over the past few weeks. And authors like Samantha Irby and James Patterson, and even Merriam-Webster Dictionary, have taken to Twitter to champion indie bookstores.

When the pandemic ends, life will certainly look different than it did before. Bookstores could play a crucial role in the healing process—but they need to outlive the crisis. “Bookstores do tend to be a gathering place for their community for everything: for book clubs, date nights, celebrations and teaching children to read,” French says. “Sometimes you don’t understand how vital something is to your world until you miss it for awhile.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Annabel Gutterman at annabel.gutterman@time.com