Early this week, a spat erupted between President Trump and the nation’s governors over who had the right to undo the stay-at-home orders that many states have imposed to protect citizens from the Coronavirus pandemic. Trump insisted his authority was “total,” governors and Constitutional experts pushed back, and the President retreated, for the moment.

It is not the first time in our history that governors and presidents have squared off. The Tenth Amendment to the Constitution gives power to the states and the people themselves, when not explicitly assigned to the federal government. But over the centuries, executive power has steadily grown at the expense of the states, especially in times of war or other emergencies.

How the current impasse is resolved could have long-term implications for these vexing questions. President Trump is correct that a national emergency usually demands vigorous action from the executive branch, especially when facing an enemy that shows no respect for state boundaries. Such actions might include summoning the nation’s leading scientists to accelerate the search for a vaccine; or using the full powers of the Defense Production Act to coordinate the manufacture of testing kits, ventilators and masks. But that is a challenge for one of the most anti-science administrations in history, further complicated by the GOP’s limited view of government and strong feelings about states’ rights. President Trump seems to want it both ways, proclaiming that he is now a “war president” but refusing to take the kind of actions Franklin Roosevelt or Harry Truman did.

Predictably, governors are stepping into the void, forming regional alliances in the Northwest and the Northeast, like republics within the Republic. Gov. Gavin Newsom even used the phrase “nation-state” to describe California. Are we headed toward a new phase of states’ independence?

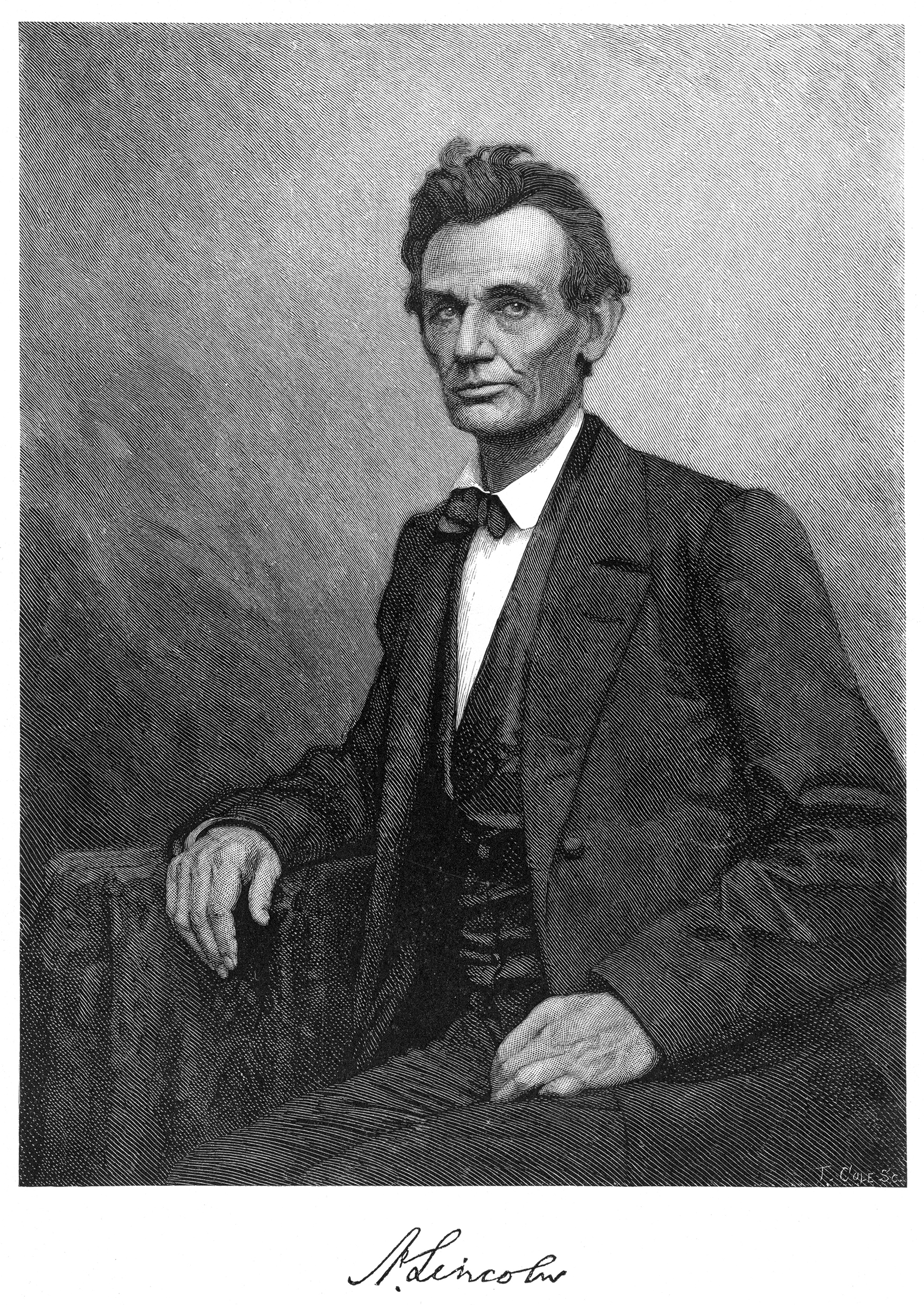

Ironically, the Republican party originated when these questions were all in the air – and decisively resolved by the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln’s embrace of science and technology was one of many reasons that the North won the Civil War. But he also displayed a masterful leadership of the nation’s governors – then, as now, an unruly bunch. No incoming president ever had a weaker hand to play, at a time when governors wielded far more power than they do now. Yet by the time he was assassinated in 1865 Lincoln had saved the country and restored the presidency. The canny ways in which he improved his chances are worth revisiting.

Lincoln is so famous that it can be difficult to remember just how obscure he was when he ran for president in 1860. His CV was as thin as his lanky frame – he had been a one-term Congressman, twelve years earlier, and had marginally lifted his profile during his losing race for the Senate against Stephen Douglas in 1858. Even as the year 1859 was ending, he was left off a list of 21 possible candidates for the Republican nomination. But the new Republican Party was dominated by its governors, and that helped Lincoln, at first. In the early months of 1860, they rejected a passel of Senators seeking the nomination, and chose Lincoln for his centrism and his ability to win critical states, including Indiana, Illinois and Pennsylvania.

Still, he held little power, even after winning the election, with a mere 39.8% of the vote, the second lowest total ever recorded (after John Quincy Adams). Despite their victory, the Republicans did not speak with one voice, in a brand new party full of governors who wanted to control the inexperienced president-elect. Then, Lincoln was weakened further after seven Southern states seceded in protest, leading to an economic slump and a deep sense of crisis. Many worried that he would not even be able to make it to Washington, full of people who wanted to prevent his presidency from beginning.

Wisely, Lincoln decided to turn the ordeal of a long train trip into an opportunity. Why not take a zigzag journey through the state capitals? He could get to know each of the governors, and greet all the people living in the small towns and big cities that lined the route. That would help to make his presidency feel real, at a time when a lame-duck president, James Buchanan, seemed to subtract federal power with every utterance.

The 1,900-mile odyssey nearly killed him, with crowds out of control, constant pressure to give speeches, and a serious plot to kill him in Baltimore. But with his rare combination of confidence and modesty, Lincoln succeeded in restoring executive power when it was most desperately needed. Lincoln reached an understanding with each of the governors he met, despite their many differences. He faced down a difficult mayor of New York, Fernando Wood, who had floated the idea of an independent city. Perhaps most importantly, he began to forge a compact with the people themselves by speaking constantly to them from his rolling stage, the train’s rear platform. With his firm command of the facts, he inspired confidence. By the time Lincoln arrived in Washington, he had already gone a long distance toward unifying a country that appeared to be on its last legs when he started his journey.

Even the train itself argued for a more coherent policy between states. As Lincoln knew from his close study of railroads, it was ridiculous to expect trains to stop at state borders, and throughout the North, they generally did not. But in the South, where state’s rights were paramount, borders were a formidable barrier. North Carolina’s trains could not connect with those coming from South Carolina and Virginia. Mississippi had a gauge unique to itself. All of Florida’s railroads except one stopped short of its boundary. Huge sections of Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi had no railroads; Texas was not connected to the South at all. It would be difficult to think of a better argument for a federal approach to solving a problem.

From the moment he arrived in Washington, that’s what Lincoln offered. Much of it was by necessity, for the challenges of raising troops and coordinating strategy were simply too difficult for the North’s disjointed governors. In the beginning of the war, states and even private individuals were recruiting troops, with little coordination. Then as now, the governors floated ideas of regional meetings, to increase their authority over a president they doubted at first. But it soon became obvious that a national emergency required a national response, coordinated by the White House. By 1863, Lincoln was firmly in charge, especially after the victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg, and the stirring speech he gave to dedicate a cemetery – a national cemetery – in that hallowed place. That was one of countless ways he improvised his way toward genuine authority, both moral and political. He would have argued that they were inseparable. With his tact, his firm command of the details, and his eloquence, Lincoln saved the presidency, along with the Union. By the end of his life – 155 years ago this week – the United States had become a different country, fortified by the very crisis that had threatened to undo it.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com