ESPN has taken noble swings at programming a sports network with no sports. But there are only so many airings of marbles races, old games and gabfests about the April 23–25 NFL draft—an event that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, feels as significant as a speck of sand—that viewers can take. That’s why fans clamored so hard for ESPN to move up its highly anticipated 10-part docuseries starring Michael Jordan, widely regarded as the greatest athlete ever to grace this earth, from an original airdate of June 2—coinciding with an NBA Finals series that no longer exists—to ASAP. People need a dose of nostalgia, and reason to anticipate any kind of shared cultural experience, now more than ever.

Luckily, the network listened. The first two episodes of The Last Dance, which chronicles Jordan’s final championship season, with the 1998 Chicago Bulls, debut on the network on Sunday, April 19. On each of the following four Sundays, a pair of new episodes will premiere on ESPN; the series will stream on Netflix outside the U.S. starting on April 20. Through previously unaired footage captured from a crew embedded with Air Jordan and the Bulls that 1997–1998 season, and fresh interviews with all the major characters—including Jordan, his running mate Scottie Pippen, coach Phil Jackson and Dennis Rodman, who went on a team-sanctioned bender in Las Vegas with then girlfriend Carmen Electra in order to clear his head a bit—The Last Dance offers raw, rare insight into a team that became the subject of global obsession. (Game 6 of the 1998 NBA Finals, in which Jordan’s final shot in a Bulls uniform clinched Chicago’s third straight championship and sixth in eight years, remains the most-watched NBA game in history, having averaged 35.6 million viewers.)

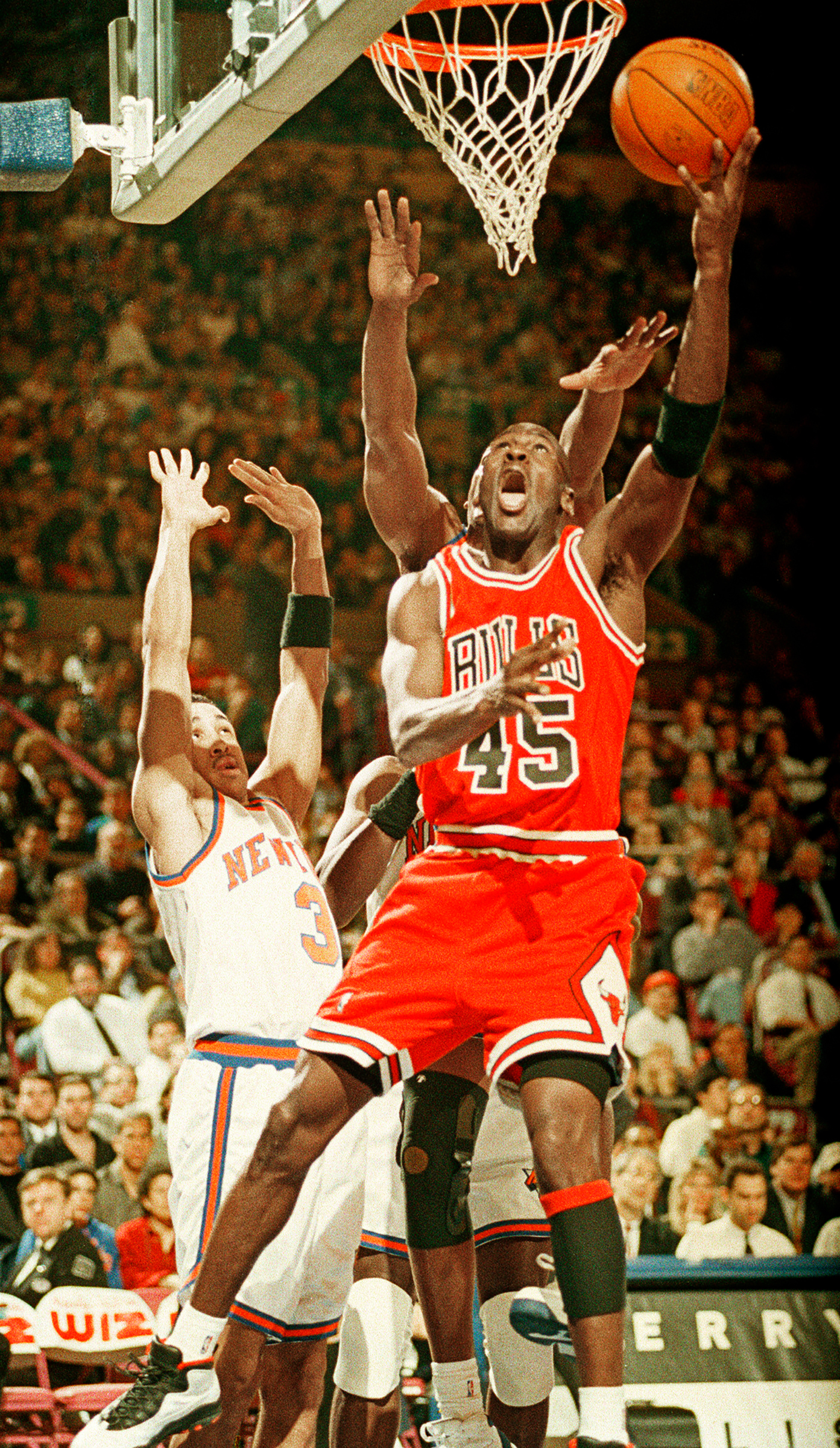

For a generation of fans who never witnessed Jordan or those Bulls teams live, the film will serve as a satisfying crash course on the MJ mystique. And while amateur Jordan scholars probably won’t discover any new bombshells, at least in the eight episodes available to the media, the project offers all viewers a useful reminder: Jordan’s career arc was unfathomably bizarre. He first retired in his prime after his father’s tragic murder, shifted to playing baseball—baseball!—then took a second forced retirement after ’98 because Bulls executives, for some still inexplicable reason, felt inclined to break up a team that did nothing but win and thrill the globe. If Jordan existed in today’s Twitter-mad, media-saturated world, the unstable Internet would have already lost its collective mind.

Moving the documentary up a month and a half to appease the quarantined masses added some logistical challenges. The final two episodes aren’t done yet, and the production crew is working remotely to see it to the finish. Before the pandemic, director Jason Hehir compared the edit process to preparing Thanksgiving dinner, where he could be in the kitchen communicating with people preparing different portions of the meal. “Now, instead, they have to send me the potatoes, send me the carrots, send me the turkey via messenger,” says Hehir. “Then I can taste and tell them what I want it to be. It’s a more roundabout process.” One of the most crucial interviews—with Utah Jazz point guard John Stockton, a key Bulls foil in the 1997 and 1998 Finals—was conducted in Spokane, Wash. in early March, just before the outbreak shut down the state and the rest of the country.

Going into the 1997–98 season, Bulls management hinted that the team’s dynasty was nearing its end. So Andy Thompson, then a field producer for NBA Entertainment—and uncle of current Golden State Warriors star Klay Thompson—thought this final campaign should be recorded for posterity. But the league needed buy-in from Jordan. An up-and-coming NBA exec, current commissioner Adam Silver, pitched the idea to Jordan; he could sign off on how the footage was ultimately used. At the very least, Silver told Jordan, he’d have the most amazing collection of home movies for his kids.

The NBA shot more than 500 hours, a haul that sports documentarians had been lusting after for nearly two decades. At the 2016 NBA All-Star Game in Toronto, producer Michael Tollin, co-chairman of Mandalay Sports Media, met with Jordan’s reps. Tollin pitched the project not as a documentary but as an event. The market for long-form epics was taking off: OJ: Made in America, the multipart doc that would go on to win an Oscar, had just debuted at Sundance. (With the continued rise of streaming services that give the films a bingeable home after airing, the demand for such docs has only grown.) Jordan, assured that the project would offer breathing room to share his full story, signed on.

Although Jordan had a hand in the project—two of his longtime business managers, Curtis Polk and Estee Portnoy, are executive producers—The Last Dance doesn’t feel too sanitized. Turns out, he’s the Michael Jordan of documentary interviewees: the best talking head in the film, honest, conversational, unafraid to unfurl profanities. We see Jordan at his most petty, like in archival footage when he pokes fun at the height and weight of diminutive Bulls general manager Jerry Krause, with whom Jordan feuded for years. (Krause died in 2017.) In one interview, ex–Bulls center Will Perdue calls him an “a–hole,” before in the next breath acknowledging Jordan was a “hell of a teammate” for pushing Chicago to greatness.

Jordan defends his ruthless motivational methods. “Look, winning has a price, leadership has a price,” he says during one interview in The Last Dance. “You ask all my teammates—one thing about Michael Jordan was he never asked me to do something he didn’t f-cking do.” The film cuts to a montage of Jordan lifting weights and running sprints. Still, Jordan tears up, a middle-aged man conflicted by his past. For once, many can relate to him.

The Last Dance also takes on the controversies, like Jordan’s penchant for gambling and aversion to politics. He famously refused to endorse Harvey Gantt, the African-American Democrat from Jordan’s home state of North Carolina, in his 1990 Senate race against conservative Republican Jesse Helms, who opposed the Martin Luther King Day holiday. “Republicans buy sneakers too,” said Jordan, whose Nike Air Jordan sneakers launched the concept of sports marketing into the stratosphere. (In the film, Jordan insists he made the statement in jest.) Even Barack Obama, an unabashed Bulls fan, admits to the filmmakers he wished Jordan had publicly backed Gantt.

Jordan’s defense: activism’s just not in his nature. He was too focused on his craft. “Was that selfish? Probably,” he admits. “But that’s where my energy was.”

While The Last Dance deserves credit for exploring this part of Jordan’s legacy, the section still feels like short shrift, given the emergence of social activism among today’s sports stars. What does Jordan think of modern athlete engagement? How do today’s stars, LeBron James and others, view Jordan’s neutrality? These questions go unanswered. Even in a documentary covering the late 1990s—and even amid a pandemic where politics has taken a back seat to more serious chaos—placing Jordan in a contemporary context feels not only appropriate, but crucial.

Such nitpicking, however, counts as part of the fun. And we sure can use a little of that. No Michael Jordan treatment, even one as comprehensive as The Last Dance, will leave everyone entirely fulfilled. Viewers can look forward to weekly debates about the documentary’s merits and shortcomings. Whether it’s during his playing days, his retirement years or a still surreal quarantine, His Airness is always worth talking about. Even from a social distance, it turns out, Michael Jordan can bring us together.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com