While COVID-19 has been dubbed “the great equalizer” by some, emerging data suggest that minorities in the U.S. are more vulnerable to the coronavirus pandemic on multiple levels. In New York City, for example, preliminary data showed that 34% of fatalities as of April 8 were within the Hispanic community, despite their making up only 29% of the city’s population. Nationwide, Hispanic and Latinx Americans are also the largest uninsured group.

In addition, only 16% of Hispanic workers can do their jobs from home. That means many are essential workers on the front lines of the pandemic fight — in New York City, they make up about 40% of employees at grocery stores, convenience stores and drug stores — and others are unable to work at all. Nationwide, about half of Hispanic people say a household member got a pay cut or lost a job, or both, as a result of COVID-19, compared to 33% of U.S. adults, per a Pew Research Center survey conducted March 19-24.

That disproportionate impact is part of the inspiration for a new video, launched Tuesday, that aims to pay tribute to the roughly 60 million Hispanic people in America and their work on the front lines of this crisis. It also provides a reminder of an often-forgotten slice of American history: the creation of the official Spanish-language national anthem.

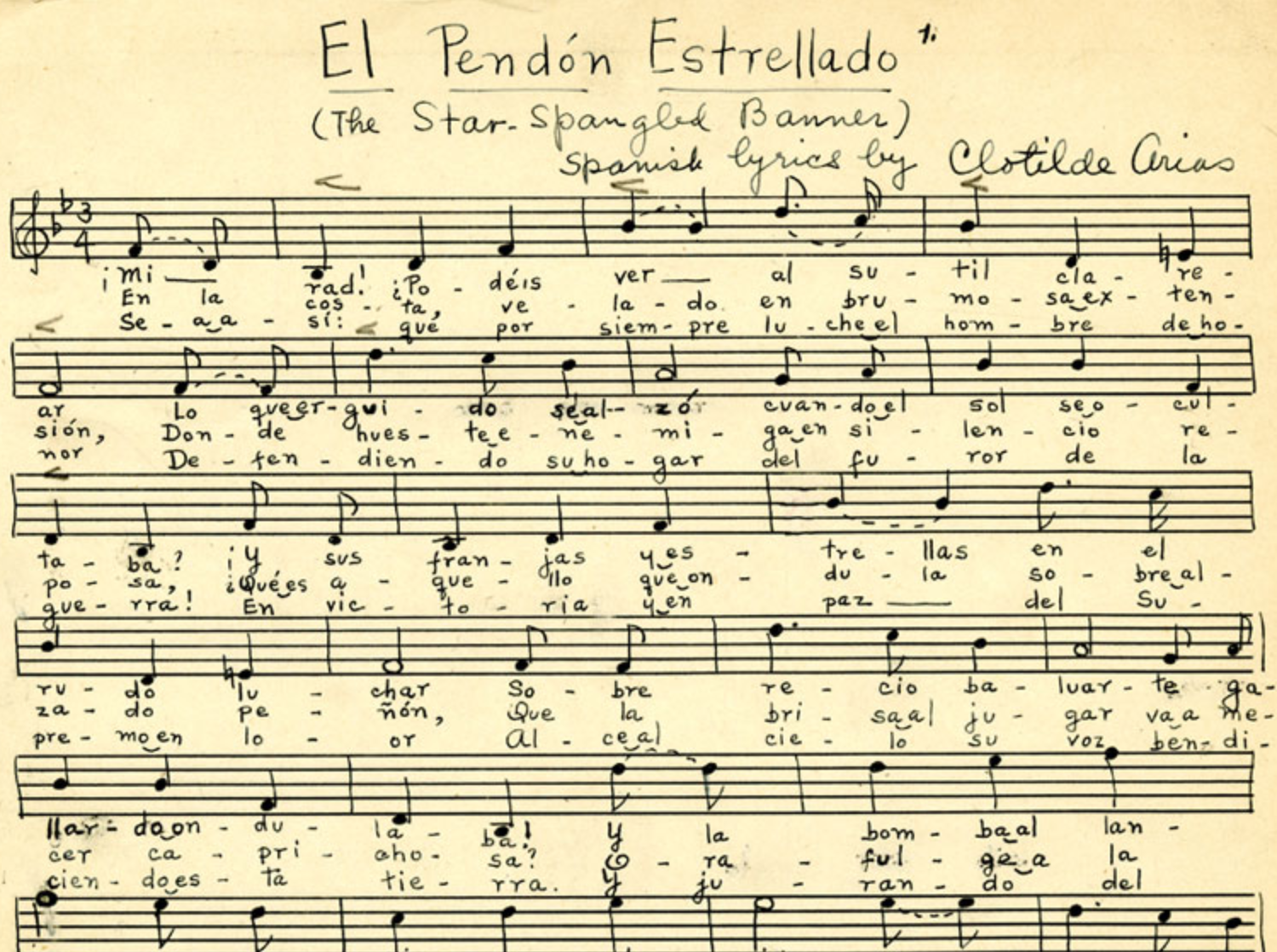

In the above video, Jeidimar Rijos, the 2019 winner of the singing competition La Voz, performs “El Pendón Estrellado” — “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The non-profit We Are All Human Foundation’s Hispanic Star campaign commissioned the video to raise awareness of its Hispanic Recovery Plan program to help connect Hispanic small businesses and workers with resources to weather the fallout of the pandemic.

The video was released the week of the 75th anniversary of the April 12, 1945, death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, because this Spanish translation of the National Anthem came about as part of his Administration’s broader strategy to appeal to the Spanish-speaking population during a different global crisis.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

In 1945, the U.S. Department of State, working with the Music Educators National Conference, put out a call for Spanish and Portuguese translations of the National Anthem.

The campaign was part of the Roosevelt Administration’s “Good Neighbor Policy,” an effort to promote good feelings about the United States in Latin American countries so that they didn’t fall under the influence of Axis countries during World War II — and so they would remain “valuable markets for U.S. products,” according to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

The government also recruited Hollywood to participate in this Good Neighbor Policy; Walt Disney went on goodwill tour of South America, hoping to find a new market for his films, and ended up producing two movies inspired by the trip: Saludos Amigos (1942) and The Three Caballeros (1944). The Brazilian star Carmen Miranda also got a boost, and her role in The Gang’s All Here made her even more famous in the U.S. And alongside these cross-cultural exchanges, the U.S. government decided it needed an anthem that could reach Spanish speakers.

Clotilde Arias, a Peruvian immigrant and New York-based composer of advertising jingles, submitted the winning lyrics. Arias had already worked on Spanish-language market campaigns for brands like Ford Motor Co., IBM and Coca-Cola. She had just become a U.S. citizen in 1942, about two decades after arriving in New York City from Iquitos, Peru, at the age of 22 to study music during the Harlem Renaissance. She would rise to oversee Spanish-language advertising at the Robert Otto agency.

In 1946, the government paid Arias $150 for her translation (worth about $2,100 in January 2020). Her version is “the only official translation of the national anthem allowed to be sung,” according to the Smithsonian.

But Arias’ translation of the “Star-Spangled Banner” never became widely known. For a 2012 retrospective on Arias, the Smithsonian could not find a recording of her translation, so it commissioned a local choir, Coral Cantigas, to perform it. The fact that the song was at risk of falling through the cracks is representative of the Hispanic community’s struggle to see its concerns prioritized in American society, says Claudia Romo Edelman, Founder and CEO of the We Are All Human Foundation.

“That’s a symbol of how there’s never been full recognition of Hispanics in America,” Romo Edelman says. She hopes Rijos’ performance raises awareness of “the contributions of Hispanics so they’re better seen, heard and valued.”

Helping Hispanic people at the front lines of the COVID-19 fight, she says, “is helping America.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com