In the two weeks since his father died, Jacob Solomon hasn’t been able to hug his mother. Nobody in his very big extended family has been able to drop by with food or to sit and listen and cry. Jacob’s mom has the same coronavirus that killed her husband, and cannot accept visitors. After he called his mother with the news, Jacob called his aunt and she drove over and tried to comfort her sister while standing in the backyard of her New Jersey home, a few feet from the window.

Grief is a lonely and confusing experience, even in less troubled times. Everybody knows it will come, but training for it is impossible. So when death calls, humans often rely on a series of rituals and traditions that anchor them to the past and the future, that draw them close to the people they have while not diminishing the love for those they have lost. People sit shiva. They hold a requiem mass. They have a memorial service, a jazz funeral, a smoking ceremony, a wake. They do not go through it alone.

But in the current season, even death has been turned inside out; the bodies are crowding together at makeshift morgues, and the bereaved are left sitting alone in a tomb of loss. The Solomon family’s experience shows how difficult that can be.

“We couldn’t dress my father in a suit,” says Jacob Solomon, 39, over Zoom. “He was buried in a pouch in a coffin. I wasn’t allowed to see him. So he went into the ambulance on Friday morning and we never saw him again. It feels like he got abducted by aliens.” Jews generally bury their dead within a day. Stephen Solomon, 72, died on Tuesday, March 24, but because of all the new protocols surrounding the coronavirus, he wasn’t buried until the following Sunday. And even then it was hardly a comforting experience.

“I don’t refer to what we had for dad as a funeral,” says Jacob. “I refer to it as a burial.” The very last blessing you can give a person, Jewish tradition states, is to put earth on their grave. But coronavirus regulations prevent the sharing of shovels, so Jacob and his four fellow mourners (his husband, his mother’s sister and her husband and child) had to bring their own, a tip Jacob had picked up from a Zoom funeral he attended in which mourners had to use their hands to put soil on the coffin. They sat apart from each other. Nobody hugged. Everybody already knew every single story in the eulogy Jacob gave.

If the burial was difficult, the aftermath was depressing. “Under normal circumstances, I would have gone back to my parents house,” he says. “All my parents’ friends would be talking to us and distracting us and remembering good times and there would be a whole lunch platter of Jewish deli-food, like whitefish and lox and the bagels. We would be comforted by the people around us.” Instead Jacob went back to his own apartment, made a turkey sandwich and ate it alone.

These small afflictions are in no way comparable to the loss of human life COVID-19 has wrought, but they compound each community’s sense of loneliness and depletion. And as the deaths pile up, so do the displaced and disoriented mourners.

Jacob’s sister is with his mom, for which he’s grateful. But they can’t tell how his mother is doing. Some days she comes to the phone. Some days she just stays curled up in bed. “We can’t tell if it’s the grief or the coronavirus,” he says. He has been on Zoom calls with his relatives, and has even performed some Jewish rituals over Zoom, for which he’s also grateful, but it’s just not the same.

His mother and sister can’t even bring themselves to use any form of FaceTime. They’re also too afraid of the virus to accept any prepared food from well-wishers. They’ve lived in a cocoon since Stephen died. “What this virus has taken away is the most valuable thing we have; that we can support each other,” Jacob says. “The hug and the touch. Thousands of years of traditions for dealing with death, they’re taken away.”

Jacob fights the thought daily that his father didn’t deserve this. Stephen Solomon was a ball of energy. His own father had died when he was 6 weeks old and he grew up poor. He sold newspapers from the age of 5. He was in the Coast Guard Reserve and had two master’s degrees. He worked as a medical devices engineer by day, but would take night shifts at Target just to keep himself engaged. He was an active member of his local temple, and when someone was needed to take the self defense training, to protect the synagogue from a tragedy like the December 2019 stabbings in New York’s Rockland county, he stepped up. “Nobody else had signed up,” says his son. In a cruel irony, it was in learning how to survive an attack that the elder Solomon caught the virus that would kill him. The instructor had it, and didn’t know.

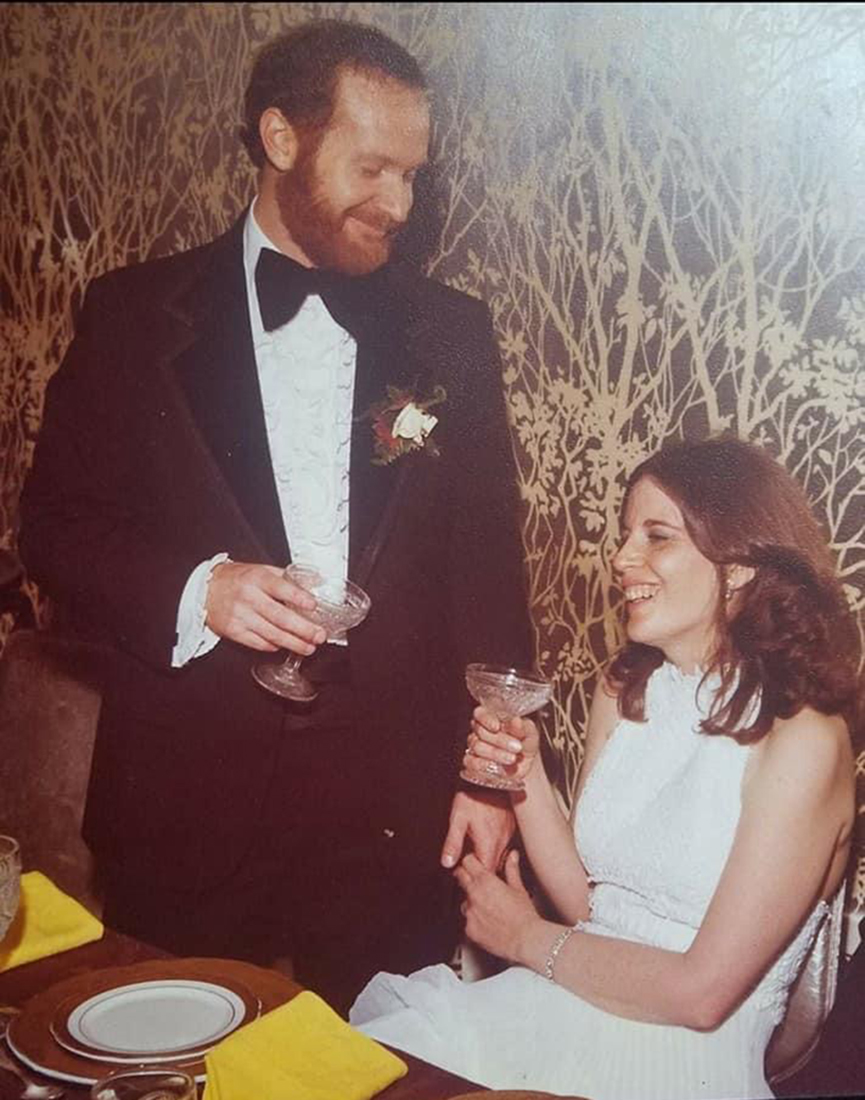

“We have a very, very large family,” says Jacob, sitting in his apartment in front of a framed piece of crochet his mom’s great aunt made. “I’m as close with third or fourth cousins as I am with first.” Growing up, his family didn’t really go on vacations. But they would travel to all the big family occasions. “No matter how strapped he was financially, if there was a bar mitzvah or a wedding my dad was there,” says Jacob. Their last trip as a family was in January to Palm Beach for his mother’s cousin’s 80th birthday.

That’s what he wanted for his father. A big family occasion. He knew everyone would have flown in. Everyone would have sent meals. “A shiva just makes sense,” he says. “It gives people something to do.” Without it, and with all the restrictions on other daily activity, there’s nothing to hide the void where the person was. “The normal life distractions to help you get through this just don’t exist. You’re just sitting there,” he says. He doesn’t want to watch the news because it reminds him of another bad day when nothing could be done. “It’s like the morning of September 11 again and again over a month.”

Jacob’s only solace is that he is stepping up and taking care of things in the way his father would have wanted. And he’s looking forward to finally embracing his mother in another week or so, although he’s dreading it too, because it will make his father’s death more real. “I just can’t imagine how painful that hug is going to be,” Jacob says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com